One of the many pieces of connective tissue between the assorted directorial efforts of Wes Anderson is the element of families, Wes Anderson loves to explore complex, typically fractured, family dynamics. Whether it’s the two brothers who lead Bottle Rocket, the expansive Tenenbaum clan or Mr. Fox and his kin, Anderson is fascinated by the storytelling possibilities offered up by complicated families. It’s a recurring narrative pattern of his that has served him well in the past, but he’s been eschewing it in his most recent works, first in The Grand Budapest Hotel and again in his newest feature Isle of Dogs. Both of these movies are superb works that indicate Anderson works just fine as a filmmaker without the aid of family dynamics in the stories he tells.

In this stop-motion animated film (his second directorial effort done in this style of animation), the whole point of the primary character dynamics is that nobody (sans for a young human boy and his nefarious Uncle) is related to one another, they’re all strangers to one degree or another trying to survive in an oppressive wasteland. Most of these characters are canines from the fictitious Japanese city Megasaki stricken by an outbreak of dog flu that threatens to soon infect the human population. Thus, Mayor Kobayashi (Kunichi Nomura) decrees that all dogs are to be exiled to the remote but massive landform known as Trash Island where they can be separated from all human beings.

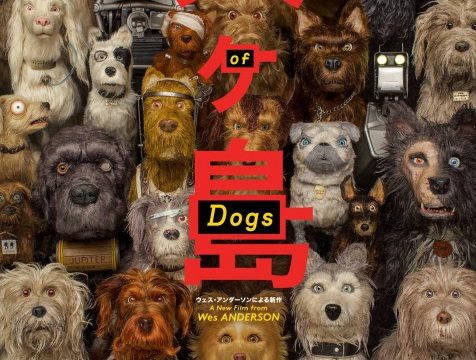

It is on this island we meet our main dog characters, Chief (Bryan Cranston), Rex (Edward Norton), King (Bob Balaban), Boss (Bil Murray) and Duke (Jeff Goldblum), who are all struggling to adapt to the harsh conditions of their new surroundings. Well, all of them except for Chief, a lifelong stray dog who’s as tough and ferocious as they come and has never needed a human owner. You can imagine then that Chief is none too thrilled when Atari Kobayashi (Koyu Rankin), the adopted son of Mayor Kobayashi, shows up to the island looking for his dog Spots (Liev Schrieber). A reluctant Chief and his other more agreeable dog pals are soon engaging in a rescue mission storyline to help this boy get Spots back.

A big rule in cinema is that you don’t hurt or kill dogs if you can help it, people (myself included) don’t like seeing dogs or any kind of animal in peril. Anderson’s kicked this rule to the curb in the past with his recurring penchant for killing off or hurting dogs, so it should be no surprise to hear that Isle of Dogs doesn’t hold back any punches in depicting the life Chief and the other exiled dogs have to live with as a miserable one full of hardship. The horrors that Kobayashi’s reign as Mayor have wrought can be felt clearly in seeing the awful conditions these dogs have to live in, though thankfully, this is clearly conveyed in a manner that doesn’t feel exploitative or overly gruesome. Simply put, this is a dark movie tonally, one that echoes bleaker 1970’s animated fare like Watership Down more than anything else.

But that darker tone makes moments of kindness truly resonate, with kindness being at the core of one of Isle of Dogs most brilliant storytelling tricks, it’s unique depiction of the relationship between a human being and a dog. That depiction heavily relies on elegant simplicity, Isle of Dogs is content to just let man and dog interact one-on-one in numerous moments of mundane activity that allows us to see the kindness-infused dedication that informs this relationship. This is especially true in one of the movies best sequences, a flashback showing Atari meeting Spot for the first time right after a traumatic car crash. We see clearly the joy Spots brings to Atari in a moment of sorrow as well as how moving Spots finds this whole set of circumstances. It’s a moment of tranquil intimacy that proves to be emotionally compelling, a terrific moment that carries a powerfully melancholy ambiance to it when contrasted paired up against the darker tone of the rest of the story. There’s plenty of other moments of small-scale pathos scattered throughout Isle of Dogs that register as similarly successful at tugging on your heartstrings and ensure that the film as a whole is one mightily poignant experience.

Though it’s frequently morose in spirit, Isle of Dogs still finds plenty of time for another prominent fixture of Wes Anderson’s work, comedy. Thankfully, the story eschews dabbling in tired dog stereotypes like sniffing butts or drinking out of toilets. Instead, a steady pace of jokes come a variety of areas, especially in terms of visual humor which take heavy advanatage of the comedic possibilities opened up by telling a story in the medium of animation. Though it may be my bias as a lover of pugs talking, some of the best jokes in the entire film come from the supporting character Oracle the Pug (voiced by Tilda Swinton, of course), whose mere act of walking into a scene had me chuckling.

Much of the humor also derives from the voicework of the cast, primarily comprised of actors who typically pop up in Wes Anderson films, who put in uniformly strong work whether they’re delivering jokes or not. Bryan Cranston’s got a wonderful voice that’s put to fine use here as Chef, while Edward Norton, Bill Murray and Jeff Goldblum score some of the biggest laughs of the whole movie in their performances, with Murray being especially a riot as a former sports mascot. Only real downside in the voice-over department, along with the fact that the voicework of Japanese actors are frequently drowned out by vocal English translations (what a weird move that is), is that Greta Gerwig and Scarlett Johansson are stuck in underwritten supporting roles that highlight how Wes Anderson really needs to pick up the slack on writing female characters in his movies, Johansson especially is stuck in a disposable love interest role that wastes her tremendous talents as a voice actor.

The numerous actors in Isle of Dogs voice characters brought to life by gorgeously realized stop-motion animation that makes the world of this movie feel like one you could easily just walk into. Richly detailed sets make the locations of Trash Island and Megasaki City pop with visual vibrancy, while the dogs themselves have endearing designs that recognize how simple character designs eschewing extraneous details (think of how the Michael Bay Transformers are covered in superfluous parts that make them ugly to look at) can be highly pleasing to the eye. The animation here is rich in details and the same can be said for the camerawork, which is heavy on visual homages to the filming styles of classic Japanese directors like Akira Kurosawa. Clearly, there’s lots of tiny details to pore over in Isle of Dogs, but some of this movies best moments come from the simple things, like recognizing how beautiful the relationship between man and canine can be.

APPENDIX: Since it’s initial release, Isle of Dogs has been subject to debate regarding its representation and utilization of Japanese culture, a vital discussion due to how often American pop culture, including high-quality movies like Isle of Dogs, can utilize Japanese culture in an insensitive manner. Justin C. Chang’s review of Isle of Dogs really got the ball rolling on this discussion and I’d urge you all to read it as well as other criticisms of how Isle of Dogs depicts Japanese culture.