Sometimes there are events that are so significant in our world that we cannot help but be affected by them. When these events occur, The Solute feels that it is part of our human responsibility to acknowledge these events and recognize their power in the world. The deaths of both Eric Garner and Michael Brown are emblematic and tragic, and their aftermaths are irrevocably part of the current zeitgeist. To not acknowledge their existence in some fashion would feel like we’re playing the fiddle.

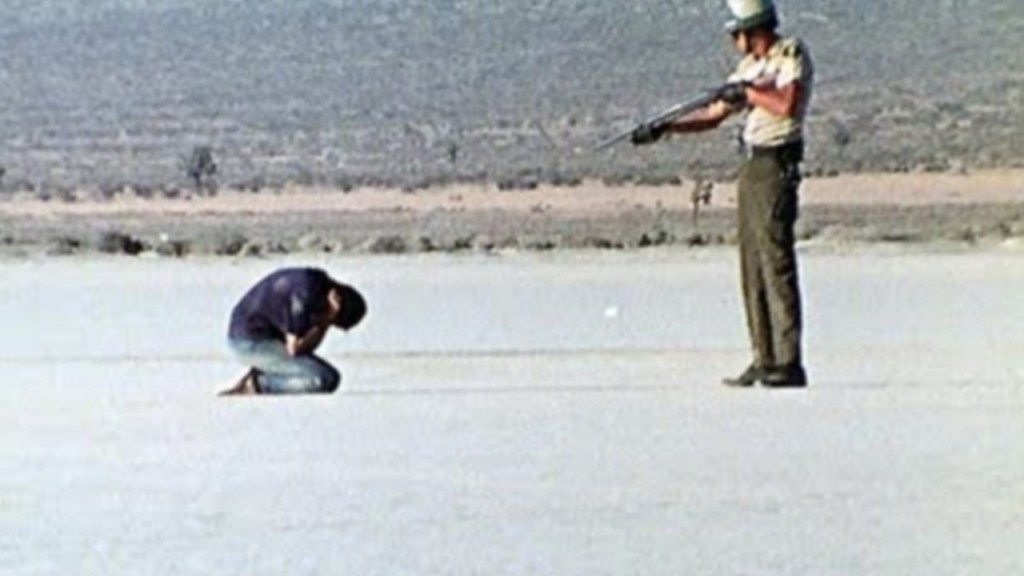

Punishment Park (1971)

director: Peter Watkins

Reflecting the satirical depiction of California as police state by Thomas Pynchon, in Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and Frank Zappa, in We’re Only in It for the Money (1968), this fictional documentary begins as Vietnam-war protesters (predominantly younger men and women) are sentenced by a citizen tribunal (predominantly older men and women). The protesters’ sentences are commuted if they play, and win, a game: the objective is to travel by foot a considerable distance across the desert, eluding capture, or possibly being killed, by police and National Guard troops, to reach the finish marked by a flag. Yet the game is rigged, for not only is there the false promise of water halfway along the route; no one is permitted to win. The players, faced with the punishing conditions, are dehumanized, their pain and suffering rather sadistically observed by the troop members, who have been instructed to regard the game as preparation for possible large-scale counter-revolutionary efforts in the U.S. The ending is unforgettable, as Watkins, who has throughout been interviewing the “actors” and providing voice over narration, attempts to physically intervene on behalf of those who have made it to the end and are being brutally beaten by the troops. This traumatic scene drives Watkins’s point home, that the cost of Vietnam has been a complete breakdown in social cohesion and communication.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993)

director: Alanis Obomsawin

On the surface, Alanis Obomsawin’s documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance already impresses with its skillful construction, allowing the portrayal of the 1990 Oka Crisis to communicate the harrowing nature of front-line conflict with hellish tension and confrontational realism. Obomsawin, unafraid of acts of hatred and violence, shrewdly utilizes her proximity to the armed stand-off between the Mohawk natives of Kanehsatake, the Québecois police, and the Canadian army, emphasizing how direly a solution to racial conflict is needed. But when one looks closer at the film’s politics, it is clear that Kanehsatake also represents one of the most important, and underappreciated, achievements in indigenous cinema history. Born of Abenaki descent, Obomsawin opts for a mostly one-sided, non-complacent agitprop style; but one cannot fault her when faced with the grossly racist attitudes of the neighbouring town of Oka, the local government’s continual claims over reserve lands, and the white-centric global news coverage. From the opening shot of a native burial ground bordered by a golf course that has been granted expansion, it is clear that using a one-sided approach doesn’t mean having to exaggerate the disparity of well-being between Aboriginal Canadians and the non-Aboriginese. By illustrating the nightmarish reality of violence, the film avoids advocating violence but posits continued resistance, and the fight for empowerment, as a solution. The title is a reminder of that need: it is only because of 270 years of resistance, since the arrival of European settlers in Québec, that Native Canadians have persevered – and Kanehsatake is a commendably resistant act.

The Thin Blue Line (1988)

director: Errol Morris

It may have spawned the most annoying “respectable” trend on network television, but Morris’s doc about the questionable guilt of Randall Dale Adams is a far cry from a 20/20 special. Instead of selectively presenting the facts to enrage his audience or get us on his side, he goes over the case again and again and again, until we see errors, then we question those conclusions, then we question those questions, and by the end we are left questioning just what “justice” even means. How can anyone ever be proven “guilty” or “innocent?” What is truth? What could have been a simple case of “lazy cops imprison the wrong guy,” is one of the greatest looks at uncertainty and it’s place in our legal system. Morris often gets credit for getting Adams off of death row, but he presents the eventual confession of Harris as an afterthought. Morris’ true concern is far more universal.

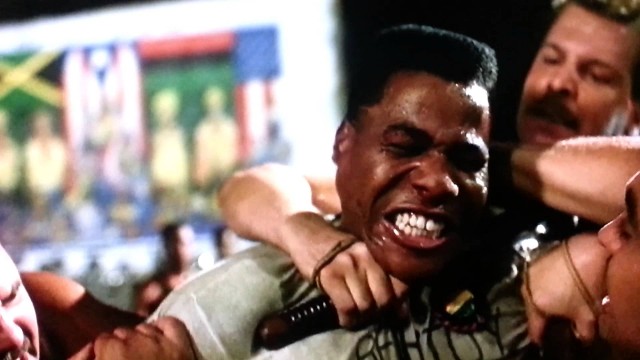

Do the Right Thing (1989)

director: Spike Lee

Just over 25 years ago, Spike Lee created his career-defining masterpiece, Do the Right Thing, a film that dismantled the racial tensions of a neighborhood in the sweltering heat of a New York summer. By creating a Black neighborhood with a Korean market and an Italian restaurant, Lee was drawing lines of race-based economic disparity where black people financed the businesses that weren’t owned by black people. Spike litters his world with political statement bombs from boxing photos to politically charged graffiti to the music of Public Enemy. Lee would extend the racial tensions when, after a violent conflict about the racial makeup on the Wall of Fame, the police end up killing a black man, and beating his cohort in a police car. Knowing there’s no accountability or justice, a mob seeks vigilante justice, and Mookie directs their aggression to property instead of body. The deaths of both Eric Garner and Michael Brown have elements that strongly recall Spike Lee’s masterpiece, even as the aftermath in Ferguson has surpassed Lee’s dramatization.