MASSIVE SPOILERS WITHIN

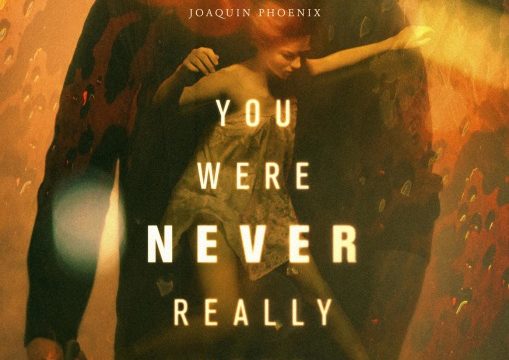

One of the most oft-repeated phrases in writing movies is “Show, don’t tell”, a logical locution to impart to screenwriters to take advantage of how much of an intrinsically visual medium of storytelling cinema is. But sometimes, it’s better to go against the “Show, don’t tell” method and leave things off-screen. The likes of Jaws and Alien have famously used this method to heighten the horror in their individual stories. Meanwhile Lynne Ramsey’s newest directorial effort You Were Never Really Here adheres to leaving acts of violence almost entirely off-screen in an effort to draw a greater sense of emphasis onto the lead characters reaction to experiencing or, far more frequently, carrying out said acts of gruesome violence and how it impacts his already damaged state of mind.

This lead character goes by the simple name of Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) and the method of keeping his violent deeds either heavily obscured or off-screen entirely is established in the first scene which sees’s him having just finished killing a man who kidnapped a young woman he was tasked with tracking down. This is how Joe makes his living now, he uses his skills from his days in the military to track down kidnapped girls and kill their captors. When he’s not taking out kidnappers, he’s taking care of his elderly mother. Kill people, then return home to help his Mom, all while coping with a fractured psychological state stemming from childhood abuse and traumatic military experiences. Lather, rinse, repeat.

The first time the audience is shown that Joe is suffering from traumatic flashbacks, there is no warning that such an element is about to appear. No set-up, no easing into it, nothing of the kind. Joe doesn’t get such a luxury when experiencing these reminders of the past in his daily life, why should the viewer? There’s just a disturbing screech, a brief image flickering by and then it’s gone in an instant, though it’s impression has been left on the viewer. This memorably perturbing moment establishes just how Lynne Ramsey, who writes and directs this feature, will be doling out glimpses into the damaged mind of Joe and it’s a method of psychologically exploring this character that proves to be appropriately haunting.

While grappling with the constant presence of these fragmented flashbacks, Joe gets his newest assignment. He’s been asked to rescue a Senator’s kidnapped underage daughter, Nina Votto (Ekaterina Samsonov), from human traffickers and the father of Nina has made it explicit that Joe is to make these kidnappers violently suffer when he rescues her. As Joe prepares for this mission, we once again get a fascinating glimpse into Joe’s mind by way of seeing how just the smallest things, like being asked by a stranger to take a photograph, can set off his hideous memories of the past and send his brain spiraling. This is a man whose only way of finding some form of brief mental stability is through the act of violently rescuing kidnapped girls, it’s the only way he can cope with what he’s seen in his life.

Ramsey finds so many fascinating ways to explore what goes on in Joe’s head and Joaquin Phoenix’s performance also helps explore the character in insightful ways. Phoenix has emerged as one of my favorite actors in his work this decade, from Her to The Master to Inherent Vice, the guy’s been doing versatile work that shows real craftsmanship. His work as Joe may be one of his best performances yet though, he’s got a chillingly effective way of communicating just in the way he lingers at a train station how much of a husk of a man Joe is. The emptiness and sorrow that fills his body is expressed in Phoenix’s body language as well as the constantly soft-spoken manner in which he delivers his dialogue. All of that agony that torments Joe’s mind is evident in the way Joaquin Phoenix masterfully portrays the character and it’s a performance that only becomes more interesting as the film goes along.

Phoenix seems to leap at the chance to explore new areas of Joe as a character as the story takes a heavy turn once Joe and Nina learn that Nina’s father has committed suicide while Nina is kidnapped by a police officer shortly thereafter. This police officer enters the story by way of shooting a man at the door of the hotel room Joe and Nina in, and once again, we see both just how much Phoenix excels in this role and how, once again, Lynne Ramsey knows just when to place the camera onto Joe’s reaction to violence rather than the act of violence itself. Blood splatters Joe’s face as Phoenix makes it perfectly clear through Joe’s facial expression that this sudden heel turn is just now starting to dawn on him. The game has changed and there’s no going back, all bets are off now.

It’s a crucial moment in the story that’s executed perfectly thanks to the merging of Joaquin Phoenix’s top-notch performance with how Ramsey keeps the audiences gaze on the characters and not carnage. Another great example of this motif in You Were Never Really Here emerges during the earlier sequence depicting Joe raiding the hotel Nina is being kept is another great example of this filming technique as the sequence is filmed entirely through security cameras that either heavily obscure or keep entirely off-screen all of Joe’s violent slayings of the guards at the hotel. Having this scene be told entirely through security camera footage is a mighty clever detail while the remarkable timing behind when exactly we cut from one security camera to another is truly exceptional.

It is in this scene that we get to meet Nina in person, a character who is brought to life by a performance from Ekaterina Samsonov. Like Phoenix, Samsonov chooses to perform Nina in an externally restrained manner that still manages to suggest an immense amount of internal turmoil. Also like Phoenix, Samsonov is phenomenal in her performance and she especially excels in depicting where the character goes in a subversive climax that has Joe setting out on a rescue mission for Nina only to discover Nina has already killed off her captor. Nina is not a prop to be used to give Joe a clean-cut arc meant to imply redemption, rather, they’re two differing portraits of what human beings who have endured cycles of abuse can become with their own individual storylines to go through.

Those individual storylines are both told in a bleak tone that renders the world Joe and Nina inhabit a cruel one with glimpses of good only existing so they can be snuffed out later by nefarious forces. That tone very much informs the movie’s score, composed by Jonny Greenwood’s, which is a tremendous collection of gripping music that manifests Joe and Nina’s constant internal woes into an excellently realized auditory form. You Were Never Really Here is, from top to bottom, a disturbing experience and also a magnificently crafted one heavily informed by Lynne Ramsey’s impressive ingenuity with depicting the psychological trauma of its two lead characters. She manages to do that by keeping so many grisly actions off-screen while making the devastating impact those actions have on the characters palpable to the viewer. In other words, You Were Never Really Here is the most engrossing and well-made kind of soul-shattering filmmaking.