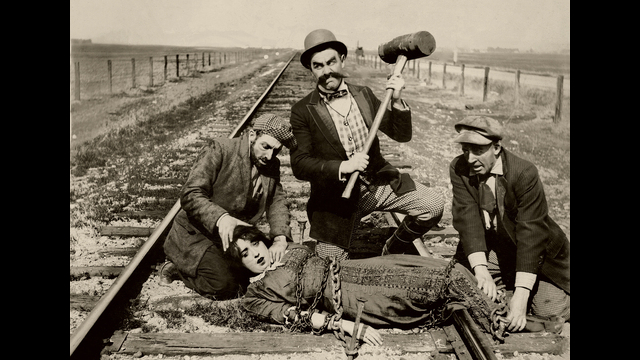

For the last two years, I’ve been watching and reviewing movie serials, mostly from the peak of their heyday in the 1930s and ’40s. I began that project, a series entitled Fates Worse Than Death, partly to spur myself to find time for a few serials I had picked up on DVD, and it grew into an extensive tour through a period of entertainment that I’ve always been interested in and which has had profound effects on the movies and TV I grew up watching. Like contemporaneous media such as radio serials, pulp magazines, and comics, movie serials were marked by broad, formulaic plots and characters, with plenty of twists and turns, emphatic action sequences, and of course the famous cliffhangers that left the heroes in peril (or seeming death) at the ends of chapters, only to be resolved in the next. Some serials (particularly those of the 1930s) had room for moral ambiguity and thematic depth, but it was primarily a medium known for thrills, wonder, and the satisfaction of seeing Evil take one on the chin.

Aside from the distance in time, there’s one way in which my experience of watching serials in the present day has been quite different from the way their original audiences encountered them, however: I would usually watch two or three (or sometimes more) chapters at a sitting, ultimately watching and reviewing the twelve to sixteen chapters of a complete film on a weekly or biweekly basis. The average serial of the interwar years is about three hours long, time-consuming but not unmanageable by any means. By contrast, the serials were originally released in weekly installments with individual episodes being part of a package that might include one or two features, a newsreel, and a cartoon. Before television, serials were a regular source of ongoing visual storytelling; and, like television before the time-shifting revolution of VCRs and DVRs, serials had to be seen on the studios’ schedules.

That’s where this new series comes in: in Tune in Next Week, instead of binge-watching, I’ll experience a serial (sort of) the way it was meant to be seen, one chapter a week, and I’ll be writing about it as I go, in the style of current TV recaps. I invite you to watch along with me and share your own thoughts in the comments. Mostly, I am curious to observe how the dynamic of watching week-to-week changes the experience: whether the frequent repetitions and continuity errors that are obvious when watching chapters back-to-back can be ignored, or whether the dramatic tension can be sustained when viewing is spread out.

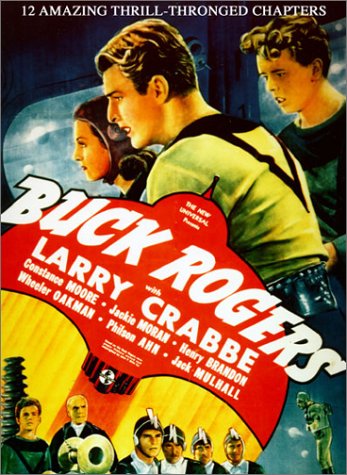

Obviously, the choice of what to watch makes a big difference in what I will have to say. Considering the resurgent interest in space opera with the release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens and the ongoing Star Trek reboot series, among others, it seemed natural to revisit one of the science fiction serials that helped to establish the cinematic vocabulary of space adventure (and that was a particular inspiration for Star Wars). I’ve already reviewed the three Flash Gordon serials as part of Fates Worse Than Death, so instead I’ll be turning to Gordon’s biggest competitor, Buck Rogers.

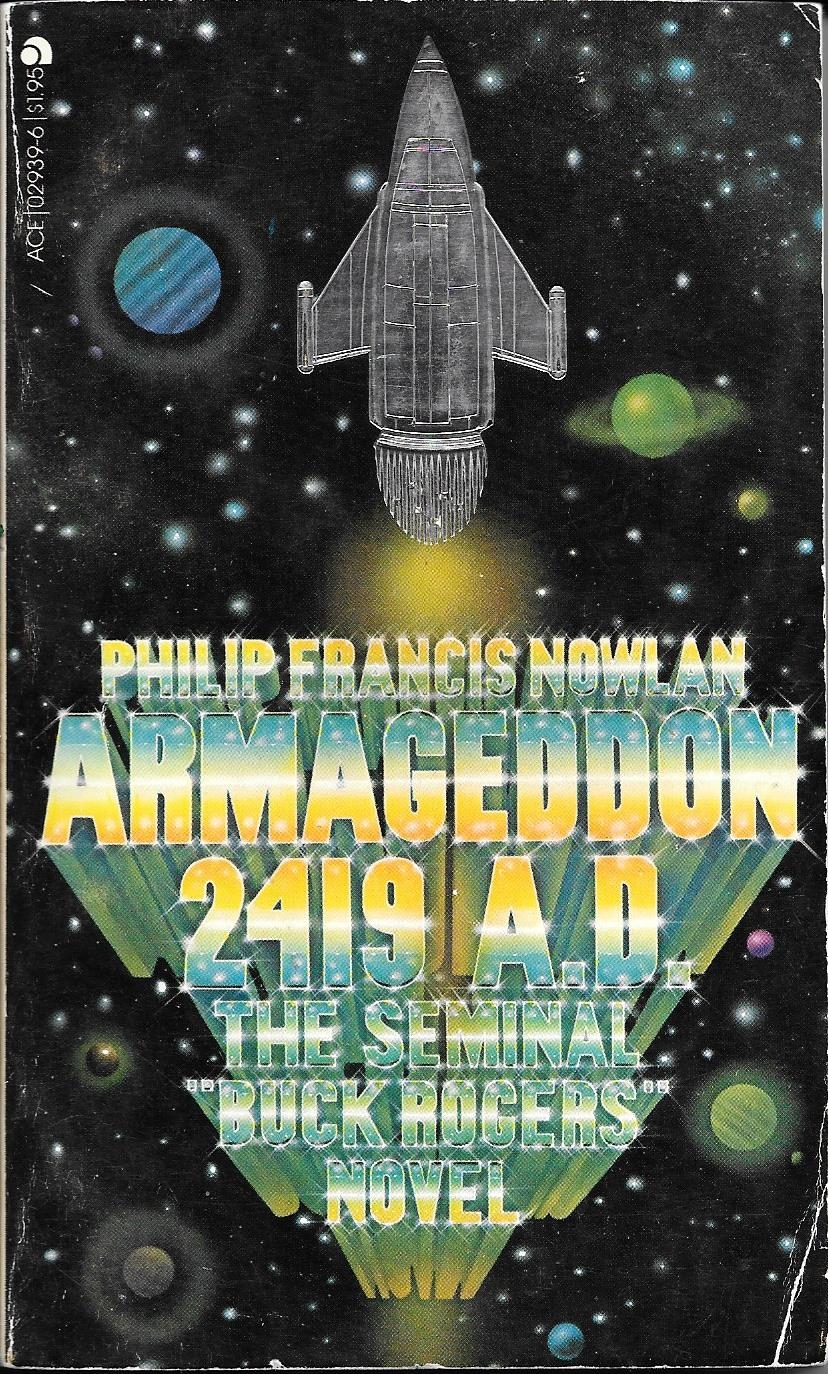

The creation of journalist and author Philip Francis Nowlan, Anthony Rogers (he would only become “Buck” later) is the hero of Nowlan’s 1928 novel Armageddon 2419 A.D. (actually two short novels that appeared in Amazing Stories and were later combined). Trapped in a mine full of a mysterious radioactive gas, Rogers is a man of the twentieth century who is preserved in a state of suspended animation, only to awaken nearly five centuries later in an America that has been conquered, its people driven underground. The conquerors are the Hans, a technologically proficient but decadent race described as “Mongolian Chinese” who crossed the Pacific and swept their disintegrator rays over America, already weakened by decades of twentieth-century war. Once having secured this part of their global empire, they have installed themselves in domed cities across North America, limiting their interest in their conquered territory to patrols that periodically cull the woodland-dwelling Americans, whom the Hans see as little more than animals.

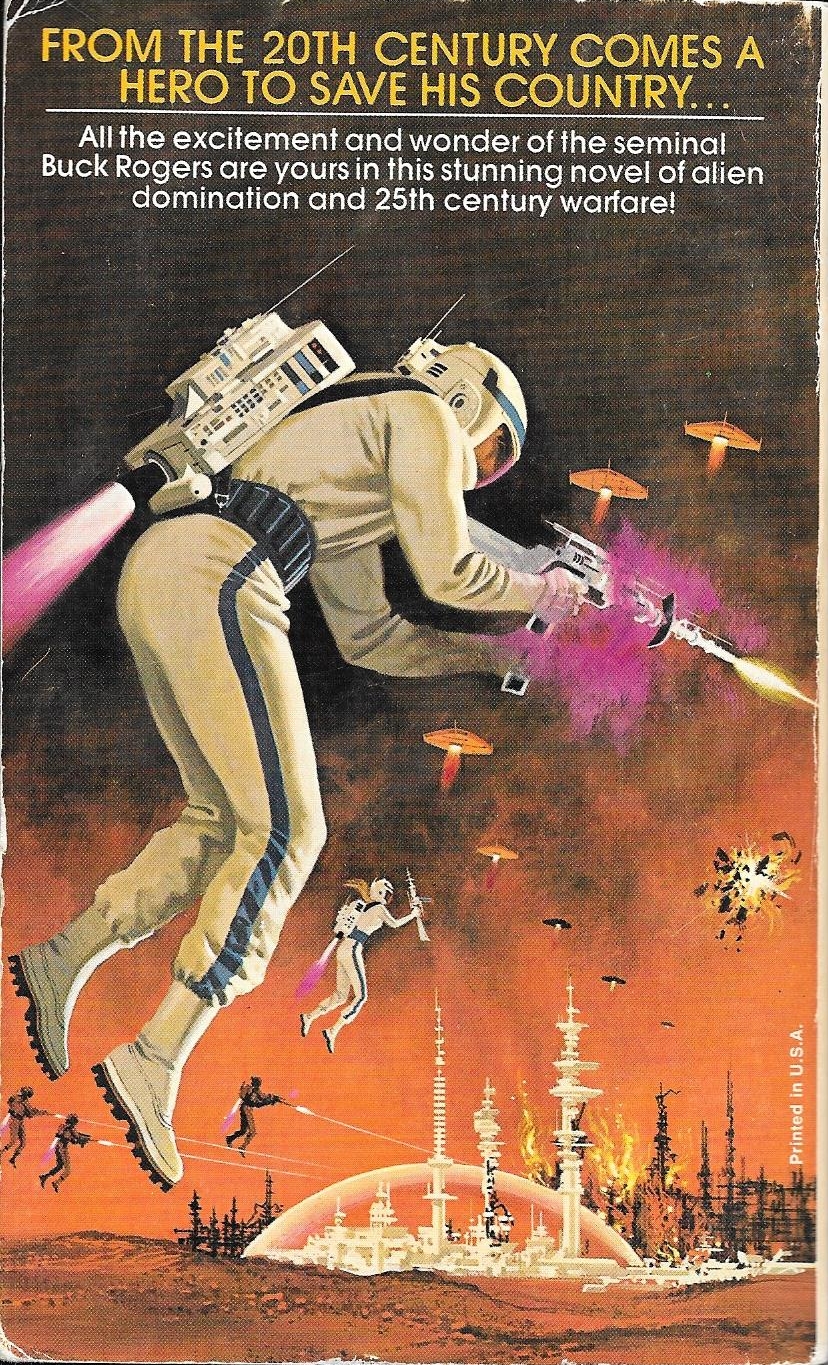

Working in secret, however, the 25th-century Americans have developed underground laboratories and factories of their own, with their own forms of super-science (including anti-gravity belts and an entirely separate spectrum of radio) unknown to the Han overlords. What they lack is organization and strong leadership, as they are divided into geographically isolated and territorial gangs. It is just at this crucial juncture in the conflict between occupiers and guerilla rebels that Rogers, a veteran of the First World War, awakens and finds himself indispensable as leader and expert on ancient military tactics. Will Rogers succeed in rallying these new Americans to overthrow the sinister Han invaders? I think we all know the answer to that.

Armageddon 2419 A.D. is, to be frank, not a good book, even by the lenient standards of the pulps. Its writing is best described as workmanlike; it is poorly paced; and much of the book is taken up with exposition that isn’t inherently interesting or germane to the plot. It is both useful and interesting, however, for what it reveals about the time in which it was written. Like many of its contemporaries, Armageddon 2419 A.D. indulges the fantasy of a great man who steps in and does what no one else can do, while warning against the softness that led to the terrible state of affairs in the first place. The Hans, of course, are a clear expression of “yellow peril,” the fear that the populous, disciplined, and ruthless Asian horde was poised to take over or destroy the West, embodied in such characters as Sax Rohmer’s Dr. Fu Manchu and his imitators, or the real-life Chinese immigrants who were frequently demonized by labor and the press as either job-stealing automatons or insidious cultural corruptors.

As Keith Phipps points out in his review for the A.V. Club’s Box of Paperback Books, the end of the book reveals that the Hans are not from Earth at all, but are alien invaders who arrived in Central Asia in the late twentieth century and interbred with the native humans, a development Phipps describes as “like calling someone an awful name and trying to smooth it over with a ‘just kidding.'” I, too, feel that this explanation does little to ameliorate the racism inherent in the Hans’ depiction, and serves only to emphasize the view of an Asiatic people–who have already in the book been portrayed as every negative stereotype imaginable–as literally inhuman. If you’re going to be racist, you might as well own it; Nowlan’s solution smacks of a writer halfheartedly trying to cover his real opinions.

Nevertheless, however retrograde Nowlan’s racial views and politics may seem to us now, he clearly favored strong, independent women, and he created a match for Rogers in Wilma Deering, a native of the twenty-fifth century whose bravery and strength are frequently compared favorably to the women Rogers left behind in the twentieth. Men and women are equals in both politics and action in Nowlan’s future. Deering is the first person Rogers meets upon awakening, and after overcoming her suspicion by holding off warriors from rival “Bad Bloods” he is accepted into her gang, and ultimately into her heart. Insisting upon sharing the danger with Rogers on his military excursions, she is sometimes put in danger, but she never comes off as a damsel in distress. (In fact, it is Rogers who is captured by the Hans and held prisoner in their capital city for months, giving plenty of opportunities for the world-building and social commentary that seems to be Nowlan’s real passion.)

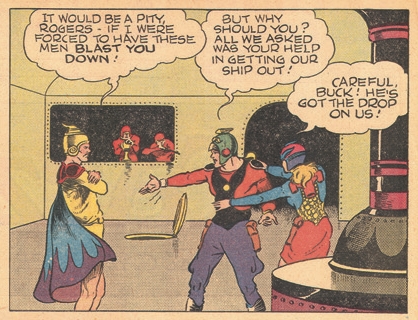

Despite its flaws as a novel, Armageddon 2419 A.D. provided the raw material for a science fiction comic strip (renamed Buck Rogers) that began in 1929, credited to Nowlan and artist Dick Calkins, and that’s where the character’s popularity really begins. The strip took Buck into outer space and armed him with an array of futuristic gadgets like the “cosmo-radio-photograph” and “electro-hypno-mentalophone.” It also introduced fixtures of the Rogers mythology that weren’t in the book, such as Buck’s ally Dr. Huer; the ruthless Killer Kane, leader of the fearsome Mongols (!); the beautiful and treacherous Ardala; and Wilma’s younger brother Buddy, who often took the lead as the hero of his own adventures.

A radio show followed in 1932, as well as books, toys, and other tie-ins. Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon strip began later, in 1934, but was the first to hit the big screen in a 1936 serial (reportedly the most expensive ever made). The Buck Rogers serial wasn’t made until 1939, and the character would continue to be an also-ran in visual media: a short-lived (and now lost) television series followed Captain Video to the small screen in 1950, and the success of Star Wars in 1977 inspired the Gil Gerard-starring revival in 1979.

While I am forearmed with some knowledge of Buck Rogers and the experience of watching quite a few other serials, this will be my first time watching this film. The experience of not knowing what comes next is part of what I hope to convey, but that carries its own risks. Many of you reading this have probably seen it already, so I beg your indulgence in this conceit. How does Buck Rogers hold up against the Flash Gordon serials? Will it be possible for me to view it objectively and place it in its historical context? Will there be enough plot in each individual chapter to sustain a series of articles? I hope you’ll find out with me. I’ll be watching Buck Rogers on DVD, but the serial can also be found on YouTube. If you’ve read this far, I invite you to check out the first chapter, “Tomorrow’s World,” and TUNE IN NEXT WEEK!