If we’re going to talk about the women’s canon, and if we’re going to talk about Fullmetal Alchemist (and we are), we need to talk about Borders. Not the geographical kind, though someone could probably write a good essay on those, too, but the bookstore.

Yes, that Borders, the ill-fated and much-missed bookstore chain that’s been gone for almost nine years. Borders had a great discount club, good selection, and a halfway decent coffeehouse. It had a missing child policy that would put the Secret Service to shame. It also was brought down, in part, by the loss of Tokyopop.

If you were a teen girl from about 2000-2010, you probably remember Tokyopop, at the time the biggest importer of manga (and a little manhua and manhwa) in the US. When it filed for bankruptcy, it left dozens of licenses in limbo and a stack of unpaid bills – including a good chunk owed to Borders. It was like watching dominoes fall; beloved manga titles suddenly stuck in nowhere, and my favorite bookstore gone. Tokyopop filed for bankruptcy in March 2011; Borders closed in November. (Tokyopop’s reorganization paid off, buoyed in part by its German-language licenses, and they’ve started publishing in the US again.)

Some of the best and most popular titles escaped the axe, as they were licensed to other publishers. Viz, always a top competitor, kept on with titles like Death Note, Fullmetal Alchemist and the Dragonball empire. Dark Horse’s few, cautious ventures into translation always sold well. But the market of cheap, easy-to-access manga had changed for good, and with the rise of digital comics, nothing would ever be quite the same. But I’ll never forget the hours I spent in Borders, always feeling a little old to be hanging out in the teen-dominated manga section, looking for my next obsession or hoping that the newest volume of Saiyuki hit the bookstores just a day or two earlier than the official publication date. There were a lot of teen boys in those sections, too, but the girls dominated, just as they dominate the current YA market, and women dominate the ‘pleasure reading’ market.

In my mind this is also when Adult Swim was well into showing anime; the original Fullmetal Alchemist anime ran on that channel from 2003-04. I watched most of it, but fell off when I fell behind on recording and couldn’t be bothered to catch up. I liked it but didn’t love it; the magic system (in fact, a steampunky blend of science and magic called ‘alchemy’) was cool as hell, the not-quite-European setting fun and the characters compelling, but when the show started showing its hand about the origins of the seven deadly ‘Sins’ – homunculi artificially created and controlled by a shadowy master – I started feeling like things were getting too predictable.

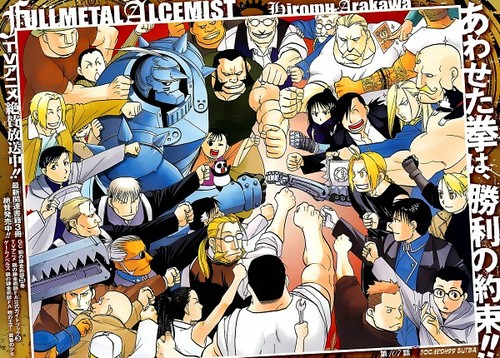

I’m not sure what got me to pick up the manga. I knew the art was beautiful and skilled – linework that would’ve made Edward Gorey a little jealous, distinctive but consistent character design, and good at depicting action and emotion – but that’s not what grabbed me, either. I honestly can’t pick the moment that got me for good, the way I can with Helllsing (“no survivors”) or Saiyuki (“If you meet the Buddha…”). But I think that speaks to the strength of what Fullmetal Alchemist (FMA from now on) was and what it becomes. Let me explain, or at least sum up.

The world created by mangaka Hiromu Arakawa starts small, with two young brothers – hotheaded, impulsive genius Edward and his calmer, kinder, and also-brilliant younger brother Alphonse – working for the local military while also pursuing their own purposes. We learn early on that, at heartbreakingly young ages, they broke one of the cardinal sins of alchemy, and suffered terribly for it. This is a pretty standard story – two plucky young kids who made a terrible mistake travel around the country helping people in need, trying to put right what went wrong, with the help and sometimes hindrance of Ed’s superior officer.

Well, it’s a standard story right up until it isn’t.

Ed and Al are indeed plucky young geniuses who made a terrible mistake. But they’re not the only ones. It’s a hell of a story when the two people who broke alchemy’s greatest taboo and tried to bring someone back from the dead, almost destroying themselves completely in the process, and then agreed to be tools of the military in a desperate attempt to get back what they lost, are relative innocents in the grand scheme of things.

The original anime, completed before the manga was finished, didn’t have a chance to dig too far below the surface. But the manga goes deep through its 27 volumes, expanding the world to encompass war, genocide, and the heavy pain of choices that cannot be undone. This isn’t a story that grabs you in a flash. This is a story that builds, that grabs you when your defenses are down. These characters may be archetypal – hothead short blond, preternaturally talented mentor hiding her own pain, know-it-all frenemy who’s more friend than enemy in the end – but they feel real, and like real people, they grow on you; some you’ll like instantly, and some you have to get to know.

FMA is ‘shonen,’ a genre that has its own rules and conventions – the protagonists are usually young men, and they’re usually framed as coming-of-age stories. FMA holds to that formula, but bends it in some deeply satisfying ways.

Unlike many battle-focused shonen titles, FMA’s narrative isn’t afraid to let the characters breathe a little. Sometimes we catch them goofing around, and one chapter early on involves the boys’ quest to be allowed to keep a cat. Arakawa follows Vonnegut’s principle that actions must serve character or story – and often serve both – but is wise enough to understand that fleshing out characters isn’t always a case of putting them in life-or-death situations. Sometimes watching the boys try to outwit their military masters is far more educational.

Shonen is often notorious for its treatment of female characters. They’re often underwritten, or shine brightly in the early chapters only to get sidelined or reduced to recurring love interests. Often there’s one Girl and a few supporting characters off in the background. Arakawa has explicitly said she worked to include more female characters, and they shine brightly. They’re not leads, but they have their own goals and interests. (They did quite well in the Japanese publisher’s popularity polls, too.) Winry Rockbell, Ed and Al’s childhood neighbor, has her own side arc, as she pursues her lifelong goal to be an automail engineer. Everyone who’s read FMA has a favorite female character, and most of us are willing to fight over her.

Shonen manga, especially titles as successful as FMA, can also struggle with finding a satisfying ending. Financial and editorial pressures often demand that a hit be extended beyond its natural life, forcing the lead characters to fight ever more powerful and absurd opponents (think Naruto) or spin their wheels in circles as artificial obstacles get in the way of the story’s natural conclusion (yes, Inyuasha, I am looking at you). FMA manages to avoid this by allowing small victories to stand, and by raising the emotional stakes as the story continues. In the end, it’s not the size of the enemy defeated that counts; it’s the growth that the characters have experienced along the way. The manga ends, and ends well, but we still don’t know if Ed and Al will ever get what they want. And that’s all right; the boys have matured enough that their original goal – restoring their bodies – is no longer enough. There are greater wrongs waiting to be put right in the world, and as the series finally ends, we see that they haven’t given up that goal. We’d expect nothing less of them.

But that makes FMA sound like an afterschool special. It neglects the laugh-out-loud moments, the heart-thumping suspense, the solid combat. It ignores the diversity and richness of the world she creates (at one point, our European heroes are baffled by the existence of a small panda, and it’s even funnier than it sounds). It definitely undersells the power of the storytelling.

There are moments in Fullmetal Alchemist where I as a reader had to stop for a second, realizing just how completely Arakawa had pulled the rug out from under me. And part of the beauty of the trick that, while sometimes people aren’t what they seem, many of the characters are exactly who we’ve known them to be all along – it’s just that we have learned something new about them that puts all our previous assumptions into a new context.

Before we dig into the conclusion, a side note on disability: FMA’s steampunk world, still recovering from a major war, is filled with characters who use automail – brilliantly crafted artificial limbs (Ed breaks his rather often, not due to lack of craftsmanship or poor materials, but because Ed tends to act, and often punch, before he thinks). Automail work is seen as a valued and important profession, and characters who use automail – including Ed himself – are not considered ‘lesser’ by the narrative. Ed is on a quest to regain his arm and leg, but it seems to be as much about putting right what he fucked up as wanting to get his own natural limbs back. Several other series regulars are disabled (including several severe injuries inflicted during the course of the manga). FMA doesn’t shy away from pain or the work of recovery – physically or mentally.

A full discussion of Fullmetal Alchemist is impossible without a good old-fashioned SPOILER SPACE. (If you haven’t had the pleasure of reading it before, please consider coming back later.)

And now we need to talk about the war. The Ishbalan Civil War is a major motivating force in both anime adaptations, and is the moral underpinning of the manga. Starting with volume 58, Arakawa goes deep inside the Ishbalan conflict to show us a truth that has only been hinted at in earlier volumes: the Amestrian military Ed serves – including but not limited to characters we have grown to love deeply – committed undeniable genocide, aided by the superior technology and murderous power of alchemy. Ed, Al and Winry are living in a world where the war is over and the bad guys won, leaving a shattered Ishbalan disapora to pick up the pieces.

In this world, redemption seems distant and difficult. Hawkeye is so devastated by her choices that she asks Mustang to literally burn the alchemic symbols tattooed on her back away, so no one else will know the secrets of the flame alchemy that destroyed so many lives. She, Mustang, and many of their allies are actively working toward a future that might end with them in military prison. They’re willing to pay that price, but it’s never clear that even that will make up for their crimes. Scar, an Ishvalan refugee turned murderer, has turned from a straightforward mission of revenge to something more complicated. Dying may bring peace but living is harder. A single act of self-sacrifice may feel powerful, but can it really make up for years of damage? Arakawa pulls away from easy answers and quick solutions. Instead, she leaves us with flawed men and women doing the best they can to make their world a little better. Sometimes, it’s all you can do.

There’s a lot of controversy over that final choice Ed makes at the gate. It seems like a no-brainer to me, honestly; Ed was always the impulsive on, the rash one, the one who found a limit and pushed it until it broke. Al was quieter, persistent, ready to take on a challenge but not as impulsive or reckless. Throughout FMA, we’ve seen what the price is of alchemy practiced without care or restraint: Ed and Al’s own accident, Izumi Curtis’s chronic pain and illness, the Ishbalan genocide, Nina Tucker. Ed isn’t very good at knowing where to stop, and he’s seen, over and over again, what happens to alchemists who are unwilling or unable to draw the line.In that final bargain, Ed may have chosen to put the brakes on himself as much as any other piece of the bargain. (He in fact notes that he could have gotten his leg back, too, but chose to keep it as a reminder.) Over and over, Arawaka reminds us that the struggle is what brings meaning to our days. (There are similar debates over the choice to restore Mustang’s sight, in the opposite direction; I’m more conflicted about that call, but find it interesting that the choice seems more about gaining and keeping power in an ableist world than ‘fixing’ Mustang’s vision.)

Arakawa grew up on a dairy farm in Hokkaido, and there’s a deep appreciation for rural life in Fullmetal Alchemist. It’s not a simplistic ‘city vs. country values,’ more a simple recognition that life in the middle of nowhere has its own difficulties and its own rewards. I think there’s a reason that in the final pages, Ed and Al are talking while Ed, now stripped (or free) of his alchemy, repairs a roof with his own hands. It’s a simple appreciation of the work that goes into living.Happiness, in FMA, isn’t about the easy choice, and that’s what makes the manga so rich and satisfying to read.