It is a truth universally acknowledged that any story that can be summed up with “a boy and his [blank]” will end up with the death of the beloved object. In the rare version where the animal lives, it is likely that a parent will die. This is true even in at least one case where it’s basically “a boy and his manic pixie dream girl.” It’s a whole genre that might be considered a rite of passage for kids about my son’s age—he’s in fifth grade and is at about the point where I expect him to be assigned something like Old Yeller or similar; what’s the current equivalent?

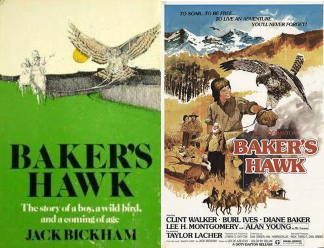

All but the first and last chapter of Baker’s Hawk, by Jack M. Bickham, are told in flashback by young lawyer William Baker. He is involved in a land deal of some sort and sees a red-tailed hawk flying over the mountains, which gets him to thinking about the one he sort of had as a boy. He’d been the sort of boy who collects animals, and he had a dozen-odd pets in his farm in Colorado. However, his father gave him an ultimatum—no more. Billy finds an injured hawk and believes he can not only nurse it to health but learn to fly it as a falconer. He befriends “the crazy man,” a hermit named McGraw who’s particularly good with animals. McGraw teaches him how to train the hawk.

Unfortunately, at the same time as this is happening, the men of the town form a vigilance committee. There’s a wild element in town, and the men want to protect their wives and children. They don’t believe the sheriff is good enough to help, so they will take the law into their own hands. Billy’s father refuses to join them. He’s seen this before and knows how it ends. The deputy is killed, and Billy’s father becomes the new deputy. And then men start to think that perhaps McGraw has an untoward interest in Billy, though it’s never well defined exactly what they think he’ll do. Kids’ book and all.

The book is mostly similar. We lose the framing device and instead gain one of the wildest casts of the ‘70s. Billy is Lee Montgomery, who is at his best a Hey It’s That Guy. But his father is Clint Walker, and his mother is Diane Baker—Lil from Marnie and Senator Martin from Silence of the Lambs, among other things. McGraw is Burl Ives. The storekeeper is Alan Young; his son is voice actor Cam Clarke, and the son’s best friend is Danny Bonaduce. You almost expect the hawk to be a famous hawk.

One of the things the book gets into that the movie doesn’t have time for is the father’s mysterious past. Oh, you expect McGraw to have one, and he almost does, but it turns out to be fairly mundane. While it’s the sort of thing that will leave its mark on a person’s history, it’s through no fault of his own. Throughout the book, however, allusions are made to a previous experience Billy’s father had with vigilance committees that become mobs. There’s a reason he won’t join, no matter the pressure placed on him, a reason he becomes a deputy instead. What happened? He never says. We just gather enough to know it’s not good.

We also lose exactly how vile Morrie Carson, the shopkeeper’s son, is. It’s suggested toward the end of the book that a lot of the actions of “the wrong element” that led to the founding of the vigilance committee in the first place may have been Morrie’s. Morrie is barely more than a child who gets caught up in things in the movie; in the book, he was basically one of the ringleaders. Even before things get going, he’s said to have been tormenting the younger boys and making their lives difficult at best and beating them up at worst. He’s the sort of person who likes making other people afraid, the sort of person who encourages the worst impulses of a mob. We get no sense of that here, no sense of how good intentions with poor foresight leads to predictable outcomes based on psychology.

From what little I know, the book’s also a decent tutorial on how to train a hawk. Certainly it’s not something I’ve ever done or would know how to do, but there’s a lot in it about how the hawk is never going to be fully tame. There’s a lot about going a step at a time. There’s a lot about how the hawk may fly away and never return, and you can never do anything about that. Okay, all of which does kind of feel like it’s setting us up for the hawk to die, but if you know anything about this sort of book, you’re waiting for the hawk to die as soon as you learn what the book’s about.

There’s also a subtle hint of the racial issues of 1880s (or so) Colorado; when going through previous local Crazy Men, Billy thinks of a black man who lived in the area briefly, and someone else explicitly says it’s illegal for black people to settle there. There’s basically nothing about gender issues; Billy’s mom exists as a character, and I think his best friend’s mother gets a line or two, and that’s it for female characters. As Boy And His [Blank] works go, it’s a bit limited. Mostly there are a handful of characters dealing with the vigilante plot, plus McGraw and the hawk for the main plot—and even there, they cross over. Still, it’s a pretty decent book, and it has a twist ending you won’t expect.

Next month, we’ll be celebrating Women’s History Month by delving into the work of Shirley Jackson. In this case, specifically The Bird’s Nest, which became the movie Lizzie. I have half as many kids as Jackson and a far smaller house to keep up, but that doesn’t mean I couldn’t do with your supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!