Basket Case, writer-director Frank Henenlotter’s bizarre 1982 horror movie, features a seemingly normal young man, Duane Bradley (Kevin Van Hentenryck), who carries a murderous secret around with him in a wicker basket. As he explores Times Square in grimy, pre-Giuliani New York City, he is constantly asked, “What’s in the basket?” Inevitably, sooner or later, the questioner finds out: the basket contains Belial, Duane’s twin brother, a clawed, sharp-toothed lump of flesh born attached to Duane’s side. Surgically separated as children, the two continued to live together in secret, and Basket Case‘s plot has two prongs: on one side, the twins wreak revenge on the doctors who separated them (and anyone else who gets in their way), and on the other, Duane attempts to start a normal life for himself while still being psychically linked to Belial. Obviously, they are bound for conflict. With a mixture of sex, violence, and comedy, it’s a weird movie in more ways than one, but its plot follows a well-trod path of sibling conflict and the distinction between “good” and “evil” twins.

After a hiatus, Henenlotter returned to this material with a pair of closely-linked sequels in 1990 and 1991. In Basket Case 2, Duane and Belial are rescued by “Granny Ruth” (Annie Ross), a “family friend” who secretly runs a sanctuary for “unique individuals”: freaks, those like Duane and Belial whose bodies aren’t typical, and who inspire fear and hatred in the “normals” who encounter them. The members of Granny Ruth’s adopted family are wildly diverse and bizarre in appearance, their deformities realized with all the latex and ingenuity the filmmakers could muster. Importantly, many of the group are whimsical rather than threatening in appearance: one looks like a mouse, one resembles the man in the moon with a fully crescent-shaped head (inspired by McDonald’s short-lived “Mac Tonight” campaign, perhaps?), and so on.

Under Ruth’s guidance, Belial appears to calm down, and even finds love with a female counterpart, Eve. External villains now include an unscrupulous tabloid reporter and her publisher who snoop around trying to get a big story out of the fugitive Bradley twins, as well as a fake freak show proprietor, but the film also inverts the plot of the first Basket Case, with Duane unable to accept that he is “one of them” and causing trouble for Belial (he eventually decides that sewing the two of them back together is the solution they’ve been looking for). Importantly, the adopted family of freaks is presented as functional, accepting, and loving (if deadly when pushed too far).

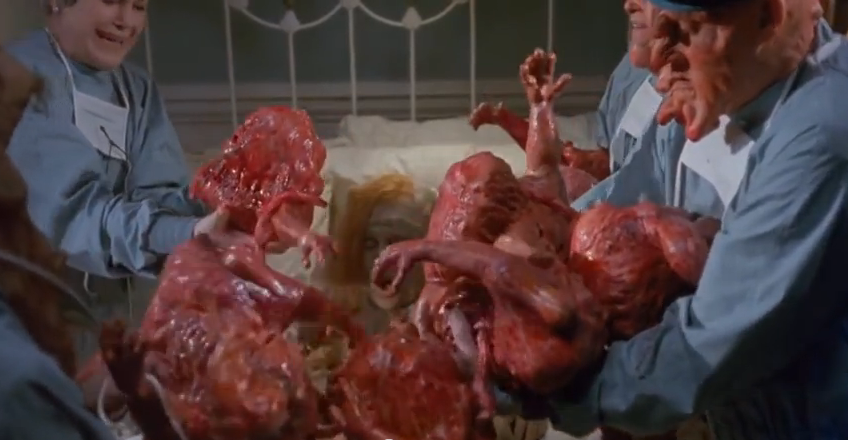

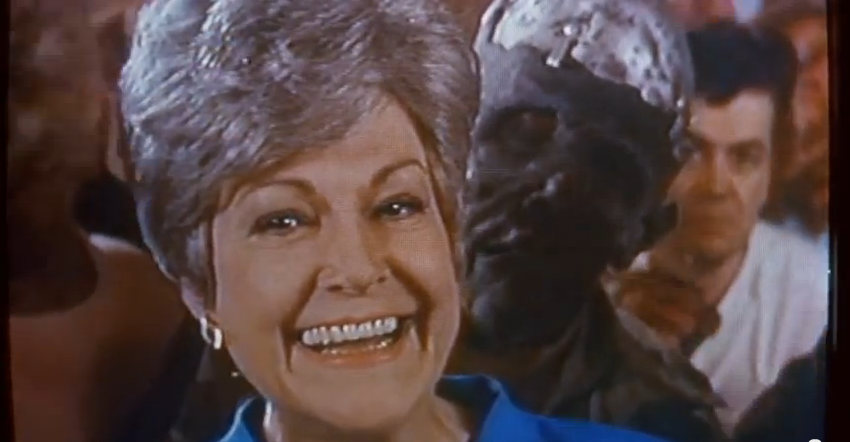

In Basket Case 3, the entire clan (including Duane in a strait jacket) takes a road trip in Granny Ruth’s school bus to visit a doctor in Georgia who can deliver Belial and Eve’s children; the villains are the small-minded local police force, and after the doctor’s house is invaded and the newborn “baby Belials” are kidnapped, the freaks get their bloody–and fully justified–revenge. The question posed explicitly in both films–what does “normal” mean, anyway?–is ultimately of less importance than how one treats others. Basket Case 3 ends with Granny Ruth crashing a Geraldo-like talk show with her posse and directly addressing the camera: “This is our world. No more hiding, no more running away. If you see us walk down the street and you don’t like it, get out of our way. We’re here to stay, and nothing and no one can ever make us hide again!” The monsters were coming out of the closet.

The two Basket Case sequels aren’t the only films to position its “monsters” as heroes, and in fact there was a small boom of such movies in the late 1980s and early ’90s. In Nightbreed (written and directed by Clive Barker, based on his novel Cabal), it’s revealed that all of the monsters of folklore are members of hidden races (the “nightbreed” of the title) that have been hunted and exterminated by “normal” humans throughout history. Some can pass for human, and in others the nightbreed lineage is so mixed that they are only carriers of the gene, but many are unable to blend in. With the last survivors hunkered down in an ancient cemetery called Midian, the nightbreed face off against the forces of organized religion, science, and law enforcement. (Although the tone is one of brooding horror rather than heroism, the similarities to X-Men, another series that used mutants as metaphors for both alienated teens and oppressed minorities, should be obvious.)

This should be distinguished from that process by which horror movie villains gradually become the heroes of their sequels, or the sense one sometimes get (as in Joe Dante’s Gremlins movies) that the filmmaker’s sensibilities are more in line with the troublemakers than the average citizens they terrorize. For that matter, classic monsters often have a sympathetic or tragic element to them: one reason for the continued popularity of the Universal monsters is the way they reflect, in a twisted way, the impulses and flaws of our shared humanity. Plus they are visually stylish and have compelling stories: the idea that the villain is more charismatic than the hero, or even has a point, is not new.

In the majority of horror movies, however, the monsters, however justified in their actions, are still at least nominally villains, the obstacles that the heroes must overcome on their way to happiness (or, failing that, tragedy). Despite the pathos of King Kong’s death, there is still no question that he has to be gotten rid of (one could certainly argue that promoter Carl Denham is the “real villain,” and that Kong should never have been brought to New York, but then there would be no movie).

The distinction of the wave of movies under discussion is that the traditional dynamic between hero and villain is inverted in the text; there is no need to make a counterintuitive “hey, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad to be a pod person” argument, because the filmmakers have clearly signaled their loyalties through the characters’ actions, dialogue, and their treatment within the film itself. These films, and the moment of their ascendance, represent the triumph of the monster kids.

The “monster kids” were those Baby Boomer children who, in the 1950s and ’60s, read Famous Monsters of Filmland and the horror comics of EC and other publishers religiously; assembled plastic models of Frankenstein and other Universal Studios monsters while poring over their TV guides for rare late-night showings of those and other classic films; and reported on a weekly basis to their local movie palaces and drive-ins for the latest sci-fi, horror, and monster movies, eventually graduating to imports from Japan’s Toho and Britain’s Hammer Studios. Anything spooky, exciting, or out of the ordinary was within their purview: anything to stoke their imaginations and combat the stultifying sameness of post-war suburban life.

At the risk of making a generalization, many of the monster kids were social misfits, apt to see themselves in the hunted, outcast monsters of the movies, comics, and magazines, and finding a clubby, welcoming atmosphere in the world of fandom. Some grew out of all this, of course, and the proliferation of beach party, hot rod, and (later) biker movies illustrate the diverse paths that youth culture could take in the 1960s. The horror genre continued to be popular, however, and many former monster kids entered the movie industry, at last able to play with the life-size versions of the toys they had grown up with.

In the 1980s, several influences converged to bring a nostalgic, utopian vision of monsterhood into the mainstream: a wave of Boomer nostalgia that brought the reintroduction of media from the 1950s and ’60s to a new audience; the increasing numbers of cable channels, hungry for material to show; and most importantly, the coming-of-age of a number of former monster kids who were now in charge of their own productions as writers, designers, and directors.

Just as importantly, the backlash to Reagan-era conservatism that had bubbled under the surface in the punky, countercultural work of John Waters and others was going mainstream. Attacks on movies and television by “moral watchdogs” put filmmakers on the defensive, and they often fought back by pushing boundaries as much as they could. In 1988’s Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, the titular horror hostess moves to the repressed town of “Falwell,” where her high spirits (and pneumatic cleavage) nearly get her burned at the stake for witchcraft. The attack on nostalgia for a ’50s that never was, made slyly in Back to the Future and overtly in Blue Velvet, left audiences receptive to a reformulation of the late-night creature feature that openly acknowledged what fans had always known: that the monsters were the stars, and secretly the heroes.

One might argue that the Basket Case movies and Nightbreed weren’t exactly mainstream, but the same dynamic is visible in movies that were much more popular and widely discussed. The time was clearly right for The Addams Family (a popular 1960s TV series, itself based on the cartoons of Charles Addams) to hit the big screen in two films (released in 1991 and 1993). The joke of The Addams Family, of course, is that while the title characters live in a gothic mansion, have macabre interests, and a lineage full of murderers, psychopaths, and eccentrics, they are as stable and loving as any family outside of a Normal Rockwell painting. While obviously a comic take on the monster family premise, it’s worth noting that in both films the threats to the family are external, from ostensibly “normal” characters who hope to exploit the family’s wealth and oddity (both times in the form of impressionable Uncle Fester, played with winning enthusiasm by Christopher Lloyd).

Perhaps the leading exponent of the monster kid aesthetic, Tim Burton, has made a career of sympathetic portrayals of outcasts and oddballs. Burton’s most personal vision of outsiderdom is Edward Scissorhands (1990), in which Frankenstein’s monster is recast as a gentle, artistic soul (played, of course, by Johnny Depp) who wants nothing more than to create and be loved, but whose metaphorically-pointed digits cannot touch without destroying. Following a pattern shared by many of the films under discussion, the normal townspeople are at first curious about Edward and his strange appearance, but are turned against him all too easily by misunderstanding and hate. Jim, the bully played by Anthony Michael Hall, is the rebuttal to all those All-American jocks who saved the day in earlier teen movies, a monster whose ugliness is on the inside, and likely a cinematic representation of real-life characters the monster kids had encountered in their own lives.

Even the conservative Disney got in on the trend with 1991’s Beauty and the Beast: who is Gaston but Jim rendered as an operatic villain? Disney was partially moved by longstanding criticism that the studio’s films reinforced prejudices: the villains were traditionally ugly or deformed, the heroes beautiful. Gaston is a perfect inversion of this, not just a handsome alpha male but an exaggeration of one, with an enormous chin, bulging muscles, and a self-confidence that becomes a ridiculous swagger. He’s popular and successful, but also vain, entitled, and (ultimately) cowardly. As he incites the villagers to storm the Beast’s castle, the film summons to mind all those pitchfork-wielding mobs that had attacked Frankenstein and others over the years, but shows it as the cynical manipulation of a demagogue looking for a scapegoat.

Obviously, the grand-daddy of all of these utopian monsterfests is Tod Browning’s Freaks, the 1932 film that shocked audiences with its sympathetic portrayal of the differently-embodied. Starring real-life circus performers, Freaks depicts its characters as a makeshift family, exploited and preyed upon by the “normals” of the outside world. Audiences of the time weren’t ready for it, and the film was suppressed and censored heavily; for years it was more spoken of than seen, but it gained new prominence as a midnight movie in the 1960s and ’70s. As with The Rocky Horror Picture Show, countercultural audiences (some of whom had probably been monster kids a few years earlier) recognized themselves in the film and celebrated the topsy-turvy inversion that elevated the “unique individuals” of Freaks over the conforming masses, the “rubes” that gawked at them. The chant “One of us! One of us!” could as easily apply to the solidarity of fandom and the midnight crowd as to the characters of the movie. The midnight movies were another important incubator for the moment under discussion.

Although I have used the word “utopian” to describe the sense of fellowship monster fans could find in many of these films, they are not above criticism. In particular, the monster kid phenomenon was largely a boyish one, and the view of sex revealed in these movies is often adolescent or even prepubescent. Gomez and Morticia Addams have a great marriage, but they are the exception. In the Basket Case sequels, sex and childbirth are just new opportunities for horror. Other films go to fetishistic extremes in their reduction of women to an assortment of body parts: Brian Yuzna’s Bride of Re-Animator (1989) and Henenlotter’s Frankenhooker (1990) riff wildly on The Bride of Frankenstein, as does Burton’s Batman Returns from 1992 (Selina Kyle’s fall and reawakening as Catwoman, and the stitches that hold her skin-tight patchwork costume together link her symbolically to the dismembered and resurrected Bride figure). What distinguishes this treatment, of course, is the sexual element, and the sense that the female body is being remade to serve a male master, both as something to ogle and as something that can be disposed of once it has served its purpose. Tellingly, we refer often to the “Bride of Frankenstein,” but I have never heard the original creature referred to as the “Groom” or “Husband.”

Furthermore, my attempts to craft a tidy narrative notwithstanding, there wasn’t just one approach to the subject matter at the time, and not all of the movies were completely successful at exploring the themes of outsiderdom and solidarity (if it were even intentional on the part of the filmmakers). Although Beauty and the Beast makes its “normal” would-be hero into the villain, the Beast also gets to be conventionally handsome after his transformation, weakening an argument that the film was progressive on standards of beauty. Catwoman, mentioned above in the context of Batman Returns, is sexualized but also empowered, a dichotomy that comics and comic book movies still struggle with, and frankly her character is only one part of all the weird stuff going on in that movie.

Even the monster kids, after their moment of triumph, were starting to look in new directions. In 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (written and designed by Tim Burton, but directed by animator Henry Selick), Jack Skellington, a king of monsters if there ever was one, surveys his Halloween domain and asks, “Is this all there is?” Here, the threat to Jack’s rule is not external, but internal, his own dissatisfaction, and his attempt to branch out into something new almost brings disaster on himself and the denizens of Halloween Town. The movie is a lot of fun, with great music and inventive visuals, but the plot is essentially the exploration of a mid-life crisis.

1994 marked an end to this phase: Burton released Ed Wood, a paean to the makeshift families of show biz (and outsiders everywhere), but one in which the utopianism is tempered by an understanding that surrounding oneself with like-minded souls doesn’t solve every problem, and that the “normals” (represented by Wood’s future wife, Kathy) can demonstrate kindness and understanding. It’s Burton’s most mature film up to that point, and while he would continue with Mad-style provocations (as in his follow-up, Mars Attacks!) and homages to classic monsters (Sleepy Hollow, Frankenweenie), he would increasingly do so as a director-for-hire and as a member of the establishment, reworking other people’s stories in his own style.

The same year, the documentary Crumb provided an intimate portrait of cartoonist Robert Crumb and his family; although Crumb doesn’t exactly fit the “monster kid” label, his devotion to obsolete pop culture and his (unasked-for) prominence as a countercultural voice give his work some of the same upside-down, satirical quality as that of John Waters and Frank Henenlotter. But Crumb the documentary is as far from utopian as it could be, demonstrating the extent to which Crumb’s work draws from his painful upbringing and ongoing issues. Readers of Crumb’s autobiographical comics covering his anxiety, sexual frustration, and dissatisfaction with modern life probably weren’t surprised by this aspect of the film, but even knowledgeable fans might have been taken aback by the realization that Robert was the most well-adjusted member of his family. Crumb shows that just surviving and continuing on can be a kind of victory, but a bittersweet one.

On another front, the release of The Interview with the Vampire signaled the (seemingly permanent) ascendancy of the glamorous, cultured vampire that had existed as a parallel strand throughout the 1980s and ’90s in such films as The Hunger (which is so coy about its heritage that the word “vampire” is not even mentioned) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (a film that attempted to have it both ways, presenting the Count as both a bestial fiend and a romantic antihero). More influenced by the style of music videos and perfume commercials than the Universal movies or Aurora model kits, these films delved whole-heartedly into adult concerns with sex, finance, and position, and with the metaphor of vampirism as addiction or sexually-transmitted disease. Kirsten Dunst’s performance as a child vampire wrestling with her newfound appetites was miles away from Christina Ricci’s deadpan Wednesday Addams, and although the popularity of Anne Rice-style vampires eventually waned, the massive success of Twilight was built on a foundation of bricks borrowed from Interview.

Still, the idea of monsters as heroes, as members of a community, was here to stay: no longer subversive or shocking in itself, but an established premise that could be deployed for a variety of thematic purposes. (The current heir to the “monster kid” throne is surely Guillermo Del Toro, who has shown a deep affection for monsters and outsiders, but also a willingness to cast them as heroes, villains, or as morally ambiguous figures in between.) Freaks, once suppressed and whispered about, is now considered a classic and is readily available to anyone who wants to watch it. By 2001, when Shrek was a hit, the inversion of fairy tale conventions begun by Beauty and the Beast was complete, down to an ending that thoroughly upended the “handsome=good, ugly=bad” formula that had reigned for so long (although I guess you could argue that short people don’t come off too well). Just within the last couple of years, funny vampire families have appeared in films for children (Hotel Transylvania) and adults (What We Do in the Shadows); the spirit of “The Monster Mash” lives on.

Stephen King has pointed out that the horror films of the ’50s and ’60s taught their audience to “fear the mutant;” if nothing else, the monster solidarity trend of twenty-five years ago showed that at least some of those kids had learned to embrace, even celebrate, the mutant within.