Conspicuously absent from the first post-Steely Dan release from Donald Fagen is the cutting mockery that made songs like “Gaucho,” a deliciously perverse tale set in a corporate penthouse, feel so singular. That brand of humor was the calling card of Walter Becker, Fagen’s co-conspirator in the Dan.

Fagen’s first solo excursion is built on a more romantic humor, an extended riff on the adolescent fantasies of “Deacon Blues” off of Aja, that 1977 record, for many, the apex of Fagen and Becker’s fusion of cool pop, studied jazz licks, and druggy in-jokes. “Deacon Blues” was Fagen and Becker’s belated acknowledgement of a teenage debt that could never be paid in full, the dream of waking when the sun goes down to play in all-night jam sessions far sweeter than the reality of such a dubious life.

The Nightfly looks back at Fagen’s formulative years in a post-WW II New Jersey suburb, many of the songs featuring a younger version of him. You can read more about his past in Eminent Hipsters, his 2013 memoir, the main attraction being a laugh-out-loud diary, written while on tour as part of the Dukes of September Rhythm Revue, which reminds us that “Deacon Blues” is an elusive dream, even in his relatively golden years.

The ironic distance between what Fagen imagined his life would be like and his writing songs about those aspirations circa the 80s is expressed as a kind of dare—so, sue him if he lets his mask slip occasionally to bask in a nostalgic afterglow. The deliberately-dated arrangements of “Ruby Baby” (a cover of a 1963 song, by ace songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, performed by the Drifters) and “Walk Between Raindrops” is one way for him to get this point across.

Another way is to give us a window into his headspace at the time. The opener, “IGY (International Geophysical Year),” rides a giddy wave of expectations felt in the late 50s—now part of the retro-futurisms of pop culture. Over a bouncy, techno-tweaked reggae beat, helium synth chords transport his lyrics like comic-book thought balloons:

On that train all graphite and glitter

Undersea by rail

Ninety minutes from New York to Paris

Well by seventy-six we’ll be A-OK

Of course, the reference to the year 1976 is loaded—signaling all is not well. Fagen has another well-used trick up his sleeve from the Dan years, the unreliable narrator who shows up in “Green Flower Street.” Here the intrigue has a second-hand staleness, as if the story were invented by a suburban American kid: the portrait of an exoticized love interest described as “my mandarin plum.” It may take a few listens to get the inner complexity, how the compact blues structure, which allows the studio-pro musicians to show off their chops, has a repetitive groove that puts a knowing chill on the youthful passion.

Like forbidden fruit, the promise of sex hangs over the album, this desire played out at varied tempos. The atmosphere of “Maxine” is languid, the fever slowly building in a Jack Kerouac-inspired travelogue set in Mexico City. The romantic getaway becomes a sardonic speculation on the pleasures found in an adult relationship:

We’ll move up to Manhattan

And fill the place with friends

Drive to the coast and drive right back again

“New Frontier” moves at a brisker pace, as the narrator envisions talking a girl into spending the night in his dad’s bomb shelter, replete with atomic imagery as sexual awakening. In a callback to “Maxine,” he tries to dazzle her with his sophisticated plans for the future:

Well I can’t wait ’til I move to the city

‘Til I finally make up my mind

To learn design and study overseas

If you were watching MTV in 1982, you couldn’t miss the video for “New Frontier“: an animated journey through space-age bachelor pads (the geometric shapes on the cover of Dave Brubeck’s seminal 1959 jazz album, Take Five, coming to life in an orgasmic swirl) and atomic survival documentaries, the phantasmagoria ending as the hatch is opened to a new dawn.

The longing for escape, Fagen knows, will take him, and Becker, into much darker places, where prolonged dalliances with controlled substances—and related scandals—would leave a lasting impression.

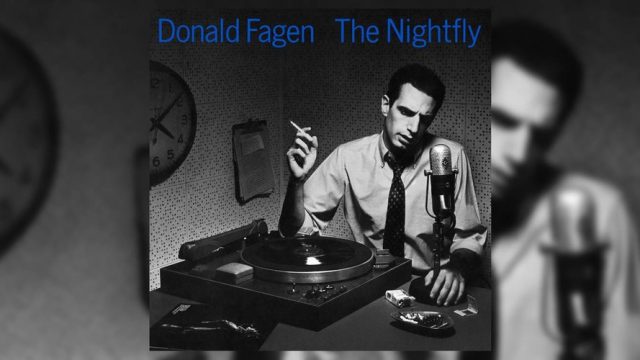

In the present-day title track, the horizon of the new dawn holds a more pessimistic outlook. We meet a late-night DJ, an older, sadder version of “Deacon Blues,” who plays jazz records and takes calls from conspiracy-obsessed listeners. The chorus, modeled after a radio station ID, is magnificent, with an expansive chord progression that gradually climbs upwards. Evoking an era when songwriters went beyond crafting simplistic hooks, “The Nightfly” is a barbed rumination on days gone by.

Given Fagen’s symbiotic relationship with Becker, you’d expect a sly tribute, and if you guessed Fagen had something in the works for the penultimate song on his solo record, you’d be right on the money. “The Goodbye Look,” while not nearly as venomous a political commentary as “Third World Man,” (the last song on the final Dan album released just as the 70s ended), has an understated tension as a lone American citizen, in the middle of a military coup on a tropical island, starts to realize the trouble he’s in. At first, he parties in a state of denial, asking, “Won’t you pour me a Cuban breeze, Gretchen?” Then, having found out that there’s been planned a “small reception just for me/Behind the big casino by the sea,” and it won’t end well, he makes a last-ditch, desperate attempt to make a run for it, hiring a boat to get him off the island.

We never know if he makes it or not. At the time, the reunion of the Dan was far off in the future—in 2000. Even now we’re not sure, at least, in the U.S, if space-age trains are going to happen any time soon. But it’s reassuring somewhat to listen to The Nightfly and soak up its cerebral cool that far outlasts the anesthesia of the 80s epitomized a year later in The Big Chill.