Many films promise to give us a picture of How We Are Living Now, but fail to deliver. Hell or High Water delivers, and in a very powerful way, indeed.

Directed by David Mackenzie, it’s the story of two brothers, Toby and Tanner Howard, who, out of sheer desperation, go on a small-scale bank robbery spree in West Texas with the hopes of getting away, free and clear, at the end. They are pursued by Marcus Hamilton, a Texas Ranger on the verge of retirement and obsessed with reliving his glory days.

By taking the naturalistic dialogue and rising tension of 70s heist films, such as The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), and using them to build a narrative that culminates in a classic Western standoff, Hell or High Water explores complicated emotional territory where the reasons for behaviors, some almost illogically extreme, are not always easy to see.

Even in the presentation of more conventional conflicts, the damage seems as limitless as the desolation of the West Texas landscape. Take for instance the scenes when Toby, the younger brother, encounters Elsie, his ex-wife and mother of his children. She projects an icy hatred of him that is the visual equivalent of “Pretend I Never Happened” by Willie Nelson (a song not in the film). There’s no flashback needed to explain what had happened. The film trusts that we can figure it out for ourselves.

Furthermore, Hell or High Water skillfully sets up our shifting allegiances between the Howard brothers and Marcus. That they all think they are doing the right thing can make them look, depending upon the circumstances, like heroes or villains.

And here the circumstances are crucial. Shots of foreclosed homes and billboards advertising debt relief point out that the populist anger of the Depression has now returned in full force. Hell or High Water takes a view similar to Bonnie and Clyde, which was released in 1967. Bonnie and Clyde was seen as controversial for its portraying armed robbery as a form of protest against the economic exploitation manifest in the predatory lending practices of banks.

Although some may conclude that the film here may be a little too on-message, the blame for the predicaments of these characters is spread around. Alberto Parker, Marcus’s longtime partner with the Rangers, has his own feelings about land ownership. Part Native American, part Mexican, Alberto reminds Marcus—and us—that others possessed the land before the banks did: the debts, aren’t only just financial; they’ve been accruing for quite some time. This is a part of American history often underreported, if not left out altogether, in textbooks.

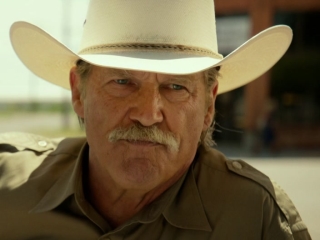

The film isn’t just a history lesson; it’s an acting lesson as well. Jeff Bridges has gained notice for his nailing the role of the archetypal lawman—and, at the same time, lets us feel his overwhelming need to live up to his reputation, one that is rapidly fading. Indeed, all of the actors reveal the duality within their characters. The younger brother, played by Chris Pine, has the steely anger of a man who’s been crossed one too many times, yet isn’t able to see much meaning to his life beyond settling a debt. Perhaps the most tragic character is the older brother, Tanner, played by Ben Foster, who is doomed by the past (a late reveal explains why) and, recently out of jail, is unable to socially adjust. He retains a family loyalty despite all he’s been through.

The film isn’t just a history lesson; it’s an acting lesson as well. Jeff Bridges has gained notice for his nailing the role of the archetypal lawman—and, at the same time, lets us feel his overwhelming need to live up to his reputation, one that is rapidly fading. Indeed, all of the actors reveal the duality within their characters. The younger brother, played by Chris Pine, has the steely anger of a man who’s been crossed one too many times, yet isn’t able to see much meaning to his life beyond settling a debt. Perhaps the most tragic character is the older brother, Tanner, played by Ben Foster, who is doomed by the past (a late reveal explains why) and, recently out of jail, is unable to socially adjust. He retains a family loyalty despite all he’s been through.

Taylor Sheridan, the screenwriter, takes a fairly common device, showing us the similarities among the three men and suggesting that they differ primarily by being on opposite sides of the law, to underwrite an aesthetic of grim, deglamorized violence. The opening song, “Dollar Bill Blues,” by the legendary songwriter Townes Van Zandt, establishes the film’s downbeat worldview. The people who reside in the dying small West Texas towns that the brothers and Marcus pass through lack the resources to go anywhere else.

Outlaws on the run chased by a lawman who’s done and seen it all make for some rather humorous moments, yet the dialogue, filled with barbed remarks, tends to make the sadness more perceptible. The characters rarely say how they really feel. In a prime example, Marcus expresses, in a comically perverse way, how he values his friendship with Alberto by making racist jokes—that are considerably more uncomfortable than funny, although Bridges gets plenty of mileage out of their delivery.

In an especially heated moment, Toby tells his older brother not to do anything stupid. What Tanner does next has got to be seen to be believed—and provides Marcus a motive for vengeance against Toby that far exceeds the crime. The film ends exactly where it should, with nothing completely resolved, reminding us that the financial crisis which fuels a crisis in ethics isn’t going away any time soon.