“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality” – Shirley Jackson

“You know what you know about? You know about how to bitch and how to eat and how to bitch and how to shit and how to bitch!” – Abel Ferrara

Movies talk to each other. A year ago, you could still go out and listen to what they had to say, listen to what other people had to say before or after or very likely during the movies themselves. The last time I hung out after a movie was with a buddy at the local bar (also the last time I went there). We had just seen Joker, a movie about a guy going insane because of society. Now the movies only talk at home. New features accessed through sites that try to still swing a few bucks toward the theaters that would be showing them, and old ones dug out of the VHS closet, pulled out of the DVD drawers, glimpsed while endlessly scrolling through streaming menus, talking out of my TV set.

“Emerald cities” is how the protagonist of Emerald Cities, an old drunk in a Santa suit played by Ed Nylund, describes what he sees on the crappy TV he has at his trailer in Death Valley. The constant green tint and fuzzy reception doesn’t change that his box is showing him strange and compelling worlds while he and his daughter live in the middle of nowhere. The world through a television screen is not enough for the daughter, who runs away to become an actress in San Francisco after meeting Ted Falconi, the guitarist for punk legends Flipper, after he stops to get gas. So Nylund, credited only as “Santa,” slowly sets out after her, hitchhiking his way into the world he’s only seen on TV.

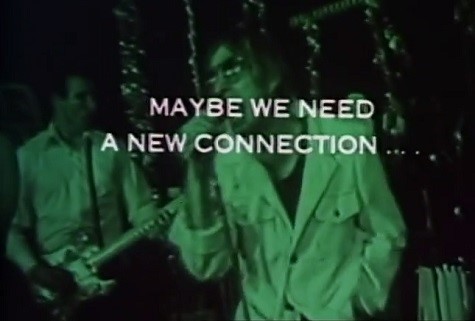

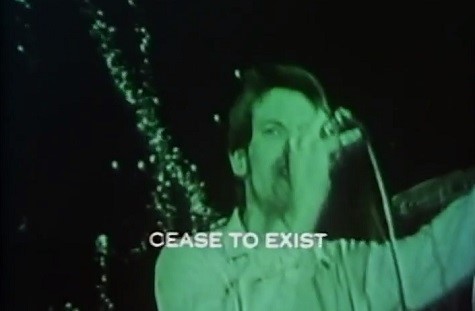

Emerald Cities was filmed over the course of several years and eventually completed in 1983 by Rick Schmidt, who literally wrote a book on no-budget filmmaking. Schmidt augments the story with narration over family photos, man-on-the-street interviews of people being asked if they believe in Santa, immediate and incredible live footage of Flipper and fellow Bay Area punks The Mutants at a Christmas gig. And plenty of news footage, Reagan and fellow goons talking about how it is “not a valid point” to move away from nuclear weaponry. “One or two Poseidon missiles could destroy the Soviet Union as a realistic society,” an official says, approvingly.

Santa wanders out of his dream, watching TV, and into realistic society. He attempts to set up his one paying gig a year of performing at a local rotary club, his flop sweat in front of nonplussed Rotarians is filmed in one excruciating, motionless take. He hits the road and is picked up by a guy who just got out of prison and is driving while wearing a full-head alien mask with no visible eyeholes; they wind up going to a New Age therapy session for the ex-con.

Nylund does not play Santa as charmingly befuddled or secretly wise, he doesn’t seem to be playing much at all – he seems like an actual confused and querulous old man. He’s mostly pathetic and sometimes hilarious in his pathos, like when his sombrero catches fire and he tries to stamp it out while his idiot calculator doohickey plays “The Mexican Hat Dance.” But he keeps moving, not letting the unfathomable reality around him slow him down. Eventually, Santa makes it to the plaza outside a subway station where that man on the street has been asking his questions. Some rando shoots him dead.

He never sees his daughter again, and while we check in with her and Falconi a few more times, the movie ends with the camera panning up a person wearing her dress to reveal Schmidt himself. The woman playing the girl who ran away from home to become an actress has herself ran away (to New York) to become a professional actress, Schmidt ruefully explains, and wasn’t around to shoot the end of the movie. It’s another intrusion of reality, along with the interviews (which don’t appear to be staged) and the concert footage and the news shows. All of this is really happening, mundane failures and weird convergences and pointless death and it’s happening under the cloud of total fucking apocalypse, people hiding in those screens and calmly talking about unimaginable body counts like it’s the most natural thing in the world because now it is the most natural thing in the world. “Welcome to the new dark ages!” The Mutants yell in the song that gives the movie its subtitle and screaming is great but why isn’t anyone else screaming? Why isn’t everyone else? Are they all watching TV, like I am?

A punk stops at Nylund’s house and destroys his life. In Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer, a bunch of punks move in below Reno Miller’s loft in 1979 NYC and drive him nuts by practicing one song over and over again, its bassline a clear theft of the “Peter Gunn” theme but with female background singers not unlike the ladies in The Mutants adding a kick. The noise is too much for Reno, who is a Serious Artist trying to finish a giant painting of an angry bison that looks like an alternate dimension Trapper Keeper cover so he can sell it and pay down his back rent so he and his girlfriend and their drugged-out lady friend don’t get kicked out in the street. That’s where there are a ton of bums, just hanging out and drinking and really waiting to be killed by a guy who has a huge drill just ready to go. A drill that needs a portable power supply – but luckily, there’s a new battery belt on the market. Reno sees this advertised on TV, of course.

The great horror critic Stacie Ponder gives this a middling review at her website, accurately writing that the acting is pretty bad and that despite having a large amount of gruesome kills to back up that title, this isn’t really a horror flick (she also astutely notes that in murdering the homeless, Reno is killing who he fears becoming). But the first half of her write-up is a recollection of her own time in New York, where the person in the apartment above her would not stop stomping around and blasting music and noisily banging his girlfriend and how it never, ever stopped. “If I stayed in that environment much longer, I would’ve given up art, gone crazy, or killed my upstairs neighbor,” Ponder writes, saying that being in the City That Never Sleeps is “fantastic – if you can get a respite once in a while.”

Part of what makes The Driller Killer enjoyable now is how it captures the reality of that bad old New York, the scuzzy streets and shitty bars, the greasy pizza that Reno crams into his mouth while the women eating with him look on in disgust. And how it showcases the crude sounds of that band, The Roosters (soon renamed as Tony Coca-Cola and the Roosters, the frontman is already letting success go to his head). I’m not like Reno, I love hearing their noise as they crowd into one of those trash bars and let the full version of the song they’ve been practicing loose with that riff bash bash bashing away and Reno is listening, the women like the band so he got dragged along to the show, and he can’t even play pinball in the bar now because of the noise and he runs into the night, of course he brought his drill and his power pack to the show and he starts stab/jabbing bums left and right, blood boiling over out of torsos and skulls, the homeless screaming in agony and no one coming to help, no one stopping Reno from chasing them down, the music following him no matter how many people he’s killing and it fucking rules, OK? It’s horrible and gross and inexcusable and it rules.

Reno is played by “Jimmy Laine,” the screen name of one Abel Ferrara, who had previously directed himself in the porno Nine Lives Of A Wet Pussy (Ferrara the actor has no sex scenes here, Ferrara the director makes sure to include several minutes of lesbian softcore shower soaping). And while Ferrara is not a great actor, he is also scuzzy and intense and just radiating wrong-o vibes at a different intensity than Nylund’s persistent eccentricity. He’s an artist but the life of the mind gives him no respite from the world. He yells about bitching and eating to his girlfriend, saying she doesn’t know anything about art, but it turns out his art dealer thinks the painting he’s been working on all movie eats shit, so what does he know? I don’t think he needs to know anything to feel right to me, though. Writing about giallos, Nick Pinkerton swipes the title of a Fulci film to describe them as a “cat in the brain” – ‘something to get inside your head and, trapped there, left to scratch and howl and spit and ruin the upholstery.” Reno can’t escape his reality but he has somehow found his way into my head, something mad and stuck.

I couldn’t take it anymore. The neighbor who’s been a nuisance for a while has gotten worse, the details aren’t important but the way he has been dealing with the pandemic is messing with my dealing with the pandemic, my sound strategy of sitting around at home. We’ve confronted each other a few times, shared angry words, but only one of us threatened to stab the other to death. (Not me, just to be clear.) We’re at a simmering détente now and I toggle between being pissed and trying to have some empathy. The guy is older and has some issues, in fact he resembles Nyland in some ways. He’s plugging along, trying to create a space outside of the reality that is crushing both of us. I can see that, and I can still throw on The Driller Killer after our last interaction. Reno has his reasons.

Reno’s girlfriend eventually leaves him to go back to her ex. So after killing a few more bums (including one poor guy who lives outside the punk band’s apartment, yelling at them to “SHUT THE FUCK UP!” – where is the solidarity, man?), Reno naturally heads over there and drills said ex while the guy is making tea and the girlfriend is in the shower. Reno hops into the ex’s bed and turns out the lights and the girlfriend snuggles up to him, unaware for the moment who she’s sharing the bed with. Fin. This leaves quite a bit up in the air but it still feels right. And anyway, one of the great things about movies, maybe the greatest right now, is that they fucking end.

Because nothing is ending now, just day after day of bitching and eating and bitching and shitting and bitching, complaining about this reality because actually taking it in is enough to drive me insane, I’ve already watched both of these movies twice. I assume it’s driven everyone else crazy already, that’s why they’re able to read statements like “Another 100,000 could be dead by April” and not lose their minds. Reality is what happens every day, whether it’s nuclear buildup or a band that won’t shut up or hundreds dying from a plague. It’d be nice to get some respite, that would be fantastic. But there is no Santa Claus.

The Mutants perform several songs in Emerald Cities and they are bitter and ironic and pissed about the world they see around them, they sing with a fury that things have gotten this bad and could be even worse. They have a vitality, living in the new dark ages and trying to escape anyway – their New Wave-y “Sofa Song” is about that classic punk boogeyman of succumbing to the settled life of material goods in the suburbs, and being fearful of something like this is its own kind of hope. That such a terrible reality could be avoided. In their performances, Flipper has no such illusions. “I want to strip the flesh from my bones!” Will Shatter howls over the crushing riff of “I Saw You Shine,” and before laying it down on record in all its negationist power, the band disintegrates while blasting “One By One.” Their final song is “Love Canal,” about the Western New York suburb where all the kids got cancer because the schools and homes were knowingly built on industrial waste. That’s reality for you, poisoned from the start and nowhere to go. All you can do is sit and wait, maybe watch some TV and try to ignore the voice that sounds like Flipper’s Bruce Lose howling over a plodding, mocking bass riff, the scream that sounds insane but is laying down the coldest reality there is: “WE ARE! DYING!”