It’s 1984, the year of clocks striking 13 and loving Big Brother, the year of Reagan destroying Walter Mondale, the year that punk broke down. The year that Jefferson Starship — formerly the freak ’60s band Jefferson Airplane, now a collection of animatronic ghouls — triumphed on Billboard’s Hot 100. “We built tThis city!” they cheered, planting the flag on a corpse they had just finished fucking. “We built this city on rock and roll!”

Jefferson Airplane got their start in San Francisco with other hopeful hippies, looking for free love and freer music. They were singing a different tune in 1984, an anthem calibrated for the sound of the times while extolling their own past, looking backward while marching forward to wealth and the glory of a pop hit. Meanwhile, the flotsam of hate and fear washed up on the beaches, and swimming in the spew was Flipper. “We built our cities of stone!” they yelled in “Survivors of the Plague.” “We built these slums where we starve!“”We are a mirror,/A distant mirror/When you look at us, you will see/All your dreams/All your hopes/Crushed upon the sea!”

It’s too pat to call Flipper a reaction to progressive failures — the band embraced and rejected failure of every sort. The paradox of Flipper is how they break down everything, falling apart in their own music but still pushing forward. How songs with maybe five notes and one groove are still put together with purpose, even if that purpose is negation. “I don’t think anything Flipper has ever done has been wrong,” writes superfan and acolyte King Buzzo of the Melvins in the liner notes* to a reissue of 1984’s Gone Fishin’. “Good music has nothing to do with technical ability. It’s powerful and dangerous and confusing insanity and I love it as much as I’ve ever loved any music that inspired me.”

Flipper had been around for five or so years at this point, putting out the debut album Generic and the greatest song in the world, “Sex Bomb,” a few years prior. “Sex Bomb” is distilled even for Flipper — one Stooges-esque bassline, one beat, one lyric (“WHAAAAAAAAAAAA SEX BOMB MY BABY YEAH”), one guitar and one saxophone battling to see who can create the most noise for the better part of eight minutes. There was really no reason to continue making Western music after this, but for some reason other people kept on, and Flipper did too, mixing a few faster songs that could at least pass for current hardcore with the slower scuzz that was their own thing. Concerts would go anywhere: the live-only track “The Wheel” could run up to half an hour, with randos from the audience joining in on vocals, before it morphed into “Sex Bomb.”

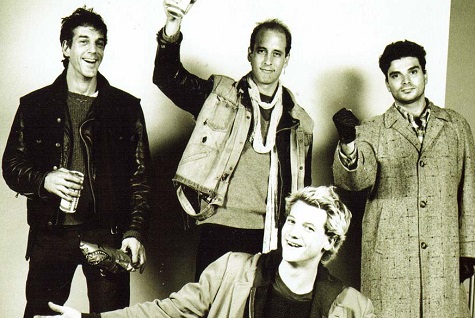

Steve DePace on drums somehow kept everything going: the more you listen to Flipper, the more miraculous his existence becomes — he could bash away with the best of them, but just marking time in the confusion and fuckery is its own skill. Guitarist Ted Falconi was the chief instigator of said fuckery — for a fun joke, go search online for Flipper guitar tabs. There are plenty of basslines, but transcriptions of what Falconi is up to are hard to find — he plays chords in shards and sheets. From an interview: “I never got the guitar to do sax riffs — I was more into jet engines.”

The rest of the band was a duo trading off — whenever Will Shatter was singing, Bruce Loose played bass, and vice versa. As bassists, the pair drove the songs, playing lurching riffs that drill into your brain and never let up — they have hooks like a butcher’s back room. The two wrote the majority of the band’s songs, and often, but not always, whichever one wrote the song sang it. Shatter’s voice is deeper, both in tone and in affect. He can be wryly amused but also drowning in despair — “If I Can’t Be Drunk” from the essential Live 1980-85 album points a straight line to his fatal heroin overdose in 1987, which destroyed the band until it was somewhat reinvented with fan Krist Novoselic on bass duties**. Loose has a higher pitch, but his narrower range comes with a tighter concentration. Loose often handled the punkier songs and their frenzied vitriol, but he is also equipped for heavier hate.

Shatter has fewer vocals than Loose on Gone Fishin’ and his side-eye — side-voice? — helps anchor the second track, “First the Heart.” It’s an abstract look at a doomed relationship written by non-band-member Jeri Wilkinson and set to a very unFlippery jerky, syncopated beat that feels more in the vein of the Contortions, complete with skronky sax — it’s a cousin to fellow 1984 oddball “Black Girls” by the Violent Femmes. Shatter sings this one, as well as “Talk’s Cheap,” which is a more familiar mode for Flipper: a cynical stomp through the meaninglessness of everyday life, showcased here by the empty gossip of friends. “Ain’t it entertaining?/Keeps your tongue in shape,” Shatter sneers. It’s immediately followed by “You Nought Me,” where Loose slaps his words over Shatter’s plodding four-note bass riff, and the cheap joys of badmouthing your friends aren’t even available here:

Sometimes I just don’t know what to do,

Constantly looking for something new.

Life’s a drag when you’re bored all the time,

Just putzing around, trying to find

Something to do to ease the pain,

And waiting for what I can’t explain…

I have nothing

Oh nothing to do

But nothing is only nothing,

And that’s not so new.

Personal despair, the meaninglessness of it all, the “confusing insanity” King Buzzo spoke of (is nothing good or bad here? What’s the point? Oh shit, is there no point?) is nothing new for Flipper. But they’re also aware of how happy others are to live off their misery, and this drives the fiercest songs on the album. “Survivors of the Plague” rides a slow, ugly bassline and lays out how survival is worse than the plague itself. “We who survived the plague, we got NOTHING!” Shatter spits out. The album’s biggest weakness is how it can place Falconi’s guitar too far down in the mix, but here it crashes and grinds — things go on, and even after the pestilence, we are being fucked. “And now the nation whom we’ve fed/Looks upon us with scorn.” Whose city has been built? Who is living there and why?

But the song’s pestilence and famine only cover two horsemen. “Sacrifice,” which is allegedly based on an anti-World War I poem and which the Melvins have covered for years (King Buzzo asserts both of these things, and he’s definitely right about at least one of them) handles the rest. Shatter wrote the song, but Loose sings it with loathing and contempt.

Can’t you smell their stinking breath?

Listen to them.

Wheezing and gasping and

Chanting their slogans.

It’s the gravedigger’s song,

Demanding a sacrifice…

So the nation will live!

So the people will remain as cattle!

They demand a sacrifice OF YOUR LIFE!

Loose is furious, DePace is marching the song to war, Shatter is running the bass riff like a meat grinder, and Falconi, well, Falconi served two years in Vietnam, working in a radio bunker subject to enemy rockets. In the song, he is off somewhere else, guitar careening along with no regard for life. Because they have no regard for yours.

Falconi is credited with the music for the album’s final song, “One by One,” and it’s the rare Flipper song that opens with a guitar playing actual notes. A relatively delicate and ominous guitar, before DePace comes in with drums and congas that forecast further destruction. And then Shatter enters on bass. Live footage of the song shows he’s just bashing the strings, and while this self-produced album has some blunders that fatally fuck with at least one song, here the sound is devastating, a tolling bell echoing forward to the heat death of the universe and reverberating back in time so John Dryden could write about it in 1687’s “Song for St. Cecilia’s Day”:

So when the last and dreadful hour

This crumbling pageant shall devour,

The trumpet shall be heard on high,

The dead shall live, the living die,

And music shall untune the sky.

The sky, the earth, the universe: all is untuned. Cutting through this this is Loose’s finest vocal, implacable and irrevocable:

Each moment,

Each road,

Every wall,

All prisons,

Every bank

Shall cease to exist.

One by one,

The waves crash

Onto the rock

And the rock, it will fall.

“CEASE! TO EXIST!” Loose bites off, over and over, with merciless certainty. The bass thunders over all, never playing real notes, never needing to, echoing, and then relentlessly rumbling into the downbeat. It’s the sea that crushed those fucking hippies in “Survivors of the Plague.” It leaves no stone unbroken, no beach unwashed. And look what it destroyed — banks, prisons, walls. Is this so bad? The darkest thing about Flipper is how the band will go as far as it can into negation and still find things to love, to celebrate without hedging.

But they also love life. Right? “Life is the only thing worth living for!” Shatter shouts across “Life,” from their first album. He sounds like he’s trying to convince himself and has a fighting chance of succeeding. And where there’s life, there’s hope, or at least the knowledge that you’re here and now, however shitty here and now may be. Maybe you can have a laugh while you’re there.

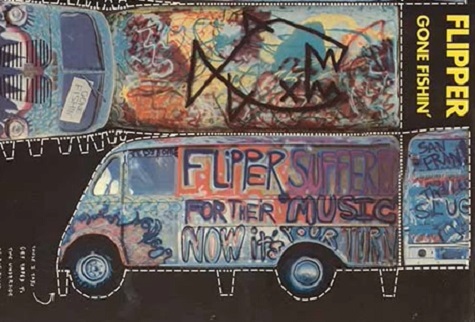

The cover for Flipper’s first album anticipates Repo Man: “Generic” is not just the name of the album but the aesthetic of its presentation — a barcode and a title on a boring background. Gone Fishin’ is far more ambitious, with the front cover presenting a cutout of the band’s beloved(?) tour bus and the back showcasing paper dolls of the band members themselves. Create your own Flipper diorama! Get an A in school! It is goofy as hell, and clearly visible on the side of the bus is the graffiti “FLIPPER SUFFERS FOR THEIR MUSIC, NOW IT’S YOUR TURN.” Seriousness and self-importance are for failed hippies; Flipper never denied its darkest moments, and it never excused its pisstakes.

“In My Life My Friends” isn’t quite a joke, but it’s cynical in its advice, which is adapted from an early 20th Century poem by W.S. Harris, “Sermons by the Devil.” Over Shatter’s furious staccato bass riff and Falconi’s thrashing guitar, which eventually overwhelm the song as they throttle each other, Loose bites off aphorisms of indifference and rejection:

Be not deceived by the toiler’s thrift,

Get what you can as nature’s gift.

Let all things take an easy drift

Til all comes right…

Rewards all come in the present slice,

So don’t look for future paradise.

Take heaven now is my advice,

And you will be right.

That’s close to hippie talk! It’s certainly not the order of the day in the mid-’80s, a time of toilers and working as hard as you can, no easy drifting. And the band wordlessly beats the riff into the ground at the end of the song — is this effort pushing back against the lyrics, or is it willing all to come right through sonic assault?

“One By One” closes the album with apocalypse, and “The Lights the Sound the Rhythm the Noise” opens it with a different kind of obliteration. And it’s an unfortunate opener in one major way: the production buries Falconi’s guitar and muffles DePace’s plodding drums and Shatter’s driving bass. Highest in the mix is a creepy, echoey clavinet; it’s a cool addition to the band’s sound, but I did not put a Flipper record on for a goddamn clavinet. The song is largely neutered.

The album’s production improves from there, and luckily there are live versions that put the meat back in the song, like one from 1983 that somehow made its way to Kazaa or Soulseek or Audiogalaxy or some damn filesharing system back in the day, where I could grab it because I liked “Sex Bomb” and I liked the name of this song. It’s raw and sludgy as shit and when Shatter’s bass rolls in at the ten-second mark, it opens up something bottomless to fall into. “The lights, the sound, and the rhythm, and the noise, hits my body like a million years,” Loose wails. “Our lives flash before our very eyes…Forever lost.”

A decade down the road, Th’ Faith Healers would tap into the infinite as an act of acceptance. Flipper is too negationist to give themselves over to anything without a fight: they put the self in self-destruction. But while “One By One” furiously thrashes into the abyss, forgoing any kind of melodic drive, “The Lights the Sound the Rhythm the Noise” rides its descending, plodding bass riff, like many a Flipper song before it. It’s something to hold on to for the band and for the listener, even as the song trudges into the void. The song’s title doubles as a description of any live show worth going to and any live show worth going to needs an audience. Flipper makes the chaos into a pact. They will harness it and we will hear it, a few humans flashing furious light together before ceasing to exist. Forever lost.

In 1984, the losers lost and the winners kept winning. It was just another damn year, no more dystopian than the one before. They built a city on rock and roll and guess what, it sucked. Rock and roll can be romanticized and faked just like anything else. Flipper resisted that: their rhythm and noise were their own, for anyone who wanted to hear it. Perfect pitch can be found by anyone with a tuner and a metronome. Flipper resonates with the frequency in my head. “If you’re never IN tune you can’t be out OF tune,” King Buzzo writes to conclude his notes on Gone Fishin’, celebrating a band of negationists and fellow survivors of the plague who walked away from the rest of the world, in tune with each other, untuning the sky.

*As always, King Buzzo is too good not to keep quoting: “Let me get something straight right now, Black Sabbath and Motörhead or bands of that nature don’t fucking MATTER to me. Those bands are horrible, horrible shit compared to Flipper and I am in no way kidding or blowing smoke up Flipper’s ass.”

**Various others have stepped in over the years, especially as Loose had to stop playing due to back injury. Rachel Thoele was on bass for the band’s 40th anniversary tour last year and Jesus Lizard madman David Yow handled vocals. This is what happened when they came to Boston.