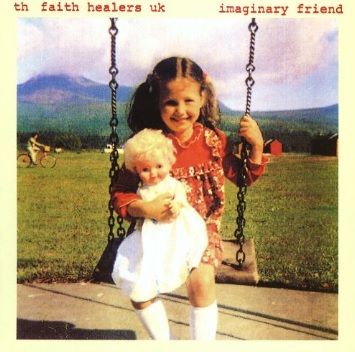

Th’ Faith Healers never gave much away. Their two albums didn’t list lyrics or even band members, and the only photos were inscrutable stock images, not the group itself. Not that they existed in a Residents-esque mystery; they gave interviews and, as befitting a British band with loud guitars in the early nineties, gained a following ready to make them the next big thing. And with 1994’s Imaginary Friend, after five years as a band, they gave up the ghost.

For most of their existence, the band worked the Bermuda Triangle between groove and riff and trance, taking the motorik of Stereolab out of the lounge and whipping it up into something fiercer. Guitarist Tom Cullinan, bassist Ben Hopkin and drummer Joe Dilworth had been playing gigs but not quite breaking through until Roxanne Stephens, who was working at a bar they were playing, asked to join on vocals. Hopkin and Dilworth rarely got fancy as a rhythm section. They were better than that, instead locking down the beat as uncrackable foundation. Culinane would layer guitars — spiky, distorted, sand-blasted, wood-chippered — as riffs knitting the songs together before ripping them apart.

And Stephens would scream or coo over all of this, sometimes intelligible, sometimes not, but always holding something out of reach, a mystery winking through the solidity of the swirling noise. Her vocals didn’t give easy hooks to hold onto, the songs were slabs you felt as the band beat the grooves into the ground. “Dolores,” one of their earlier tunes, is a good example of Th’ Faith Healers’ sound, Cullinan exploring all areas of skronk over seven minutes while Stephens promises to “whisper in your lobe.”

It’s a sound that is endlessly listenable, but in 1994’s Imaginary Friend, the band decided to augment it with mixed results. A lot of Faith Healers songs start at 10, if not 11, and the tension comes from how the repetition refuses to let up over a churning, driving tempo — the question is not when things will explode, but when they will stop. Imaginary Friend dials the tempos down to mid-speed, allowing for groove but less momentum, like opener “Sparklingly Chime” and its alternating riffs. And it instead mines tension from a loud/soft dynamic. “Heart Fog.” in particular, has a Pixies influence in its clean, quarter-note bass-led verses, but the Pixies rarely flipped the switch on their choruses this way. Stephens and the rest of the band careen into a distorted despair, wailing “Don’t say nothing now,” knowing it’s already too late.

But there’s such a thing as too much quiet. “Kevin” plays with a similar dynamic to diminishing returns, although it has some nice dentist-drill guitar work, and while “Curly Lips” has a sly vibe and some of Stephens’ deceptively airy vocals, it kicks into gear too late. These are still good songs, just missing the charge and weight of their other work. Even a nice chunk of distortion like “See-Saw” feels clipped by the generally slower tempos of the album. “The People,” though, is another highlight, pushing forward anxiously in its verses led by clean yet ominous guitar only to stomp down on the ferocious chorus, shards of distortion flying everywhere around a great line of ownage: “Don’t want a conscience, give me a reason.”

In some ways, it’s a classic Difficult Second Album. But it was also the last album, and maybe the band knew it — they’d break up shortly after its release. So they ended it with something that took some of the dynamics they’d been playing with but also doubled down on their past, literally — their debut album’s closer ran nearly 10 minutes and this final track is 20 minutes of “Everything, All At Once, Forever.”

Hopkin’s bassline is a perpetual motion machine, momentum looping it around itself as Dilworth’s drums take a cue from the Funky Drummer, laid back and pulsing. Cullinan’s guitar skitters and then the most massive riff outside a Sleep record tears open the song, a supernova dilating like a god’s eye, and time goes away. There are shifts and movements throughout: at one point the guitar shivers through a riff like the song is coming apart, and at other points it’s clean when the song downshifts before building up again, and Stephens sometimes sing-songs behind the wall of noise, the only clear words the title of the song. The full version on YouTube was taken down; it’s in two parts here but should be listened to whole if at all possible.

Because it is everything, it is happening all at once, it does feel like it can go on forever. I first heard this driving down I-95 and I’ve listened to it a bunch of times on the highway since. As a driving song, it removes the car and the road; there’s only the motion and being part of it. Wallflower, discussing Elliott Carter, gets close to what is going on here: “Narrative involves some sense of necessity, of leaving things out, and Carter continually pushes his work to be all-inclusive… They’re closer to their own living but isolated worlds, and he gives you a tour of it.” But the world of “Everything” implacably expands and absorbs. It makes the listener a component of an all-encompassing entropic world, but that is not a reduction, just a recognition. The final explosion somehow cracks even more distortion in the background, buzzing with the background hum of the universe itself.

It ends, of course. It has to. And there is a hidden track (remember those?) of the same song, but in a demo version; the recording is less layered and a bit sketchier, and it’s not bad but probably a mistake to put it on the album, even as a bonus. Maybe the band wanted to give us more of the song, but its brilliance is that even when it stops it feels like it’s playing somewhere else. An ending that doesn’t end. All bands eventually die, but not many of them can claim forever.