Memorable movies emerge when their unique limitations become assets. There’s Val Lewton’s low budgets, Steven Spielberg’s malfunctioning shark and Herk Harvey’s background as an industrial and educational filmmaker. Harvey’s Carnival of Souls is the one and only feature credit for the director of such shorts as “Why Study Speech?” and “Pork: The Meal with a Squeal”. His day job at the Centron Corporation in Lawrence, Kansas gave him a comfort and competency around the equipment, technicians and schedules of a low budget film shoot, but little practice with other narrative filmmaking skills like extensive set design or eliciting nuanced performances from his actors. Carnival of Souls appropriately occupies a strange place between worlds: It’s an amateur production put together by professionals.

Souls began with a place. Harvey, travelling back to Kansas from a Centron shoot in California spotted the isolated remains of a carnival pavilion on the edge of The Great Salt Lake in Utah. The abandoned structure was a shuttered boardwalk attraction called Saltair. Birthed by the Mormon Church in 1893 as an attempt to provide a wholesome Coney Island that could keep out the less savory elements of carnivals, Saltair was destroyed by a fire in 1925. It was rebuilt but the resurrected versions were never accepted in the same way. In 1958 Saltair was closed for good and given to the state. Three years later, in disrepair at the terminal end of an abandoned train track and reeking of dead brine shrimp, the corpse of Saltair fascinated Herk Harvey who conceived a movie around this relic of happy days gone by.

Harvey returned to Kansas and directed his friend and fellow Centron employee John Clifford to write a feature that would feature Saltair at its climax. Clifford took a similar location-oriented method to writing the rest of Souls. “While thinking about a character and a story, I was also trying to think of locations that would put atmosphere on the screen at little expense,” he writes in his notes for the Criterion release of Souls. He wrote the script in three weeks.

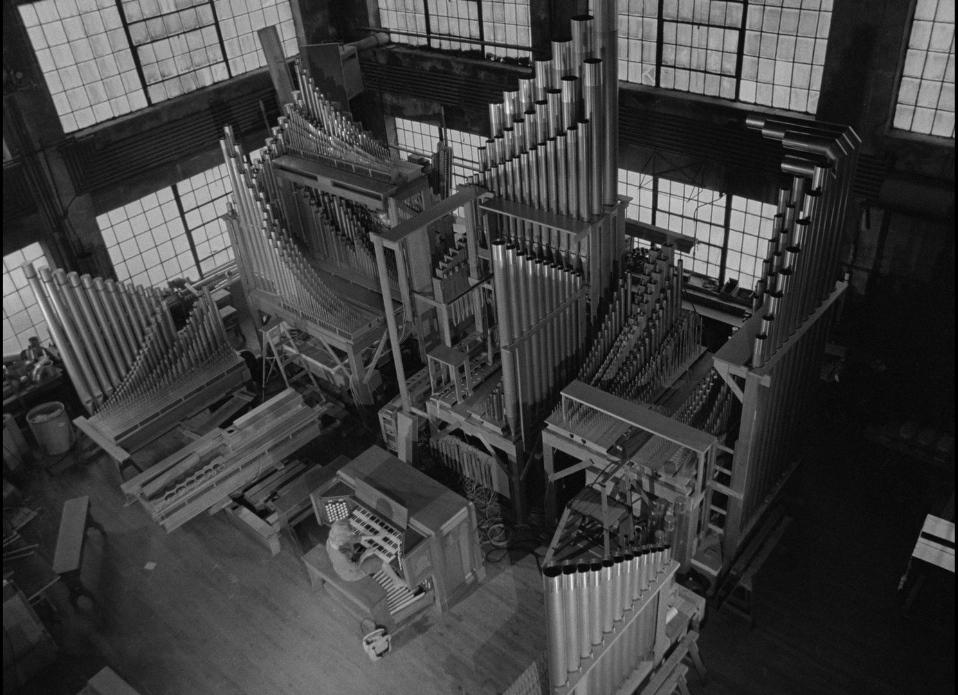

The resulting story moves between locations chosen because they were either appropriate for or, more often, available to the cash-strapped production. In the movie, Mary (Candace Hilligoss) is the apparent lone survivor of a car wreck that leaves two other women dead at the bottom of a river (the local Kaw). She lives an isolated life as an organist in Lawrence, Kansas (established in a Lawrence organ factory at the base of a massive pipe organ) and leaves to take a new job at a church in Salt Lake City (actually a historic church about ten blocks from Centron’s studios). Along the way she’s haunted by a ghoulish man (played by Harvey in heavy white makeup) and by a flesh-and-blood creep rooming in the same house as Mary. Mary spots Saltair from the road and finds herself drawn there even as she finds it increasingly difficult to navigate the world of the living. You can likely see where this is headed. Reportedly in the 1962 it was less obvious.

There are many things people claim to find appealing in a movie and one of them is a certain degree of verisimilitude. Carnival of Souls does not always provide this. The dialog is overblown and given alternately stiff and hammy deliveries by non-professional or inexperienced actors. “I wrote fast and little time for revision, and it was my first film,” John Clifford says defensively in his Criterion notes, (while making sure to point out “screenwriters also write the quiet, eerie atmospheric scenes”). But leaving aside the subjective value of these things – e.g. Lynch fans will not argue that natural performances are always desirable – these shortcomings do not interfere with the film’s frequent appeal as a moody and artful work.

In his Centron films, Harvey was used to providing a visual naturalism rather than a performative one. Performers were responsible for their own wardrobe, hair and makeup and give an unfiltered glimpse of daily fashion in the early 1960s (or, this being Kansas, possibly the late 1950s). With one exception that requires a ghostly effect, vehicles are filmed with handheld cameras on real streets rather than using a process trailer or rear projection on a soundstage. Lacking the resources to build sets (aside from a single-sided psychiatrist’s office), Souls takes place entirely within real business and real houses, the action spilling onto streets of unaware passersby (a couple of whom make furtive glances at the camera).

Providing a horror bent to verité-like footage comes naturally to Harvey, and the titles of a few of his other credits like “Dance, Little Children” (1961) and “Shake Hands with Danger” (1979) suggest there’s a fine line between health and horror films to begin with. Harvey shoots his locations largely with unassuming objectivity – the organ factory may have been a comfortable selection not just for the excuse it provides for the film’s eerie soundtrack. But he possesses the eye to make frames pop as well. The organ itself feels like it sprawls even as it’s contained within the frame – a monstrosity somehow responding to the impossibly small figure playing it at the bottom.

Harvey’s fascination with Saltair permeates his quiet, unsettling compositions of the pavilion viewed from afar. Before it turns into a funhouse of sorts, the interiors have a quiet menace as Mary explores the decrepit rooms. The camera discovers along with her, rather than presenting a construction made with the camera in mind. The contrast of locations does much of the heavy lifting from a thematic standpoint. Mary is drawn away from these real, living spaces populated by real people, basically unaltered from their day-to-day look and compelled towards a real, dead space in Saltair, a rotting space with roots in spiritual aspirations that has absorbs and reflects decades of dreams and failures.

Souls found belated success during a revival on the festival circuit in 1989 when the technical knowledge to produce a competent film was still relatively scarce. Audiences familiar with that other early 60s film about a blonde moving from her hometown toward imminent danger, Psycho, knew what an auteur could conjure from scratch. In Souls they discovered what a craftsman could make out of the spaces we move through every day.