The missing link between Richard Lester and Peter Greenaway, A Clockwork Orange bears the look and themes of its time and place more than any other Kubrick film since Fear and Desire. Watching it, I had much the same reaction as I have to Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers or early Cronenberg: an appreciation of the themes and the skill in executing them that stops short of actually liking the movie. If we consider the second half of Kubrick’s career separately from the first, this a classic gonzo, overstuffed second film that follows an acclaimed debut, the kind where a director can indulge himself in whatever comes to mind.

Indulge himself he does; Clockwork is the most visually busy and aggressive of all Kubrick’s films. Slow motion, fast motion, point-of-view shots including one from Alex’s (Malcolm McDowell) as he jumps from a building, imagined sequences, fast cutting, cuts to paintings, rear projection, a production design straight from Ken Russell (“More nudity! More genitals!” I imagine Kubrick yelling; with the curves and blobs of the art and the lettering, it’s the most 1971 aspect of the film), and a lot of the old zoom-in, zoom-out. Contrasting to this, he stays in and around London for the entire movie; this is the only one of the later Kubrick movies that’s filmed where (and when, sort of) it’s set. It’s the most naturalistic setting he’s used since Killer’s Kiss, and the least realistic style.

At least a few elements of this are interesting as well as excessive. One aspect that works is the repeated use of stages and proscenium arches, with the camera hanging back and watching from a distance. The fight that takes place in a theater, early in the film, is as staged and composed as a martial arts demonstration, with precisely one piece of furniture broken per shot. Coupled with the yob-Victorian narration from Alex (straight out of Anthony Burgess’ novel, I believe), it makes Clockwork feel more like a pageant than a proper story, with a set of incidents and spectacles played for our benefit; heightening the style like this inevitably makes us aware of not just the director’s presence but our presence as an audience. Another element of style is the use of women’s bodies as mannequins, something that also goes back to Killer’s Kiss. There he used real mannequins, but here it’s naked women, almost always still, almost always in a fashion model’s pose. In one scene, these two ideas come together, with a woman (Virginia Wetherell) on a stage for Alex to get sick over and demonstrate the success of the Ludovico technique for an audience. Kubrick shoots her like a statue from Alex’s POV, looming over him and us, and when it’s over, she breaks into a smile and does a perfect dancer’s exit. (Darn, she’s real after all.) We’ll see this again in The Shining and Eyes Wide Shut; visually, Kubrick presents women naked but without any sensuality, certainly nothing like the sensuality of the men of Spartacus. In these films, women are substitutes for statues and mannequins, a neat reversal that I’m sure a lot of theorists have already written up. (If not, contact me and we’ll start talking prices.)

The color scheme is the best part of Kubrick’s style here. He signals it right away with the credits; it’s bright and lurid and dominated by primaries but stops short of the Technicolor-level saturation of Spartacus or the Star Gate sequence in 2001. In doesn’t heighten the look of what’s there and it’s not a hallucination either. This is an entirely artificial world, but not a dream world. The sets give the same feeling; the statues of naked-women-as-furniture echo the couches and chairs in 2001’s space station. It’s one step short of psychedelic, the look of the world from the perspective of someone coming off a trip, or better yet, a world made by people coming off a trip (the “ultimate trip” of 2001 perhaps? The soundtrack appears in the record store, and Alex replaces a Ligeti microcassette with Beethoven early on) and trying to replicate that in the world.

That’s not a bad description of 1971 England. A Clockwork Orange, as much as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, is about the hangover of the late 1960s, when the energy had started to burn out and liberation began to seem like a bad idea. Alex’s slightly unruly Beatles haircut tips us off to that, but it’s something embedded in the structure of the movie. It’s the story of Untamed Youth, the cunning plans and crazy capers of A Hard Day’s Night pushed into rape and ultraviolence, and Burgess’ insight was how that youth would be tamed. Burgess makes Alex a psychopath, a rapist, a killer, and also more culturally sensitive than everyone else (a trope that goes from Bram Stoker to Thomas Harris), but he doesn’t just use this character as a warning. He and Kubrick portray how this character gets brought back into society.

That’s done, of course, through the aversion therapy of the Ludovico Technique, where doctors condition Alex into becoming sick at the thought of sex and/or violence. That allows a priest (Godfrey Quigley) to raise Clockwork’s most interesting question, on the difference between good/evil and sick/healthy: if we condition people to not do evil, can there be any real good any more? For the most part, this isn’t played out beyond “yes, it is possible to do this,” although the plot of Alex getting tortured by one of his victims (Patrick Magee) demonstrates that there’s no getting rid of the need for revenge. The staginess of Clockwork reinforces the sense that we’re seeing a morality play, but if it is one, the morality has to be much more interesting than this; The Vanishing and Bad Lieutenant both hit similar themes with much more force.

The priest’s question gives Clockwork has a fair amount of power, though, especially at the end. That ending can be read as the failure of the Ludovico Technique, and Alex will be back to his old ways soon enough, this time with government sanction. He was going to be the poster child for the Technique, and now he’ll do the same for its opponents. The ending can also be read as identical to Brazil: the man who attempted to escape society’s system has been captured at the end, and he only has his mind as refuge; whether the ending is fantasy, and if it is, whether it’s essentially different from Sam Lowry’s, is left as an exercise for the reader. (Both films end with a key piece of music to signify literally transcendent pleasure.) Also left as an exercise: which ending is the more despairing?

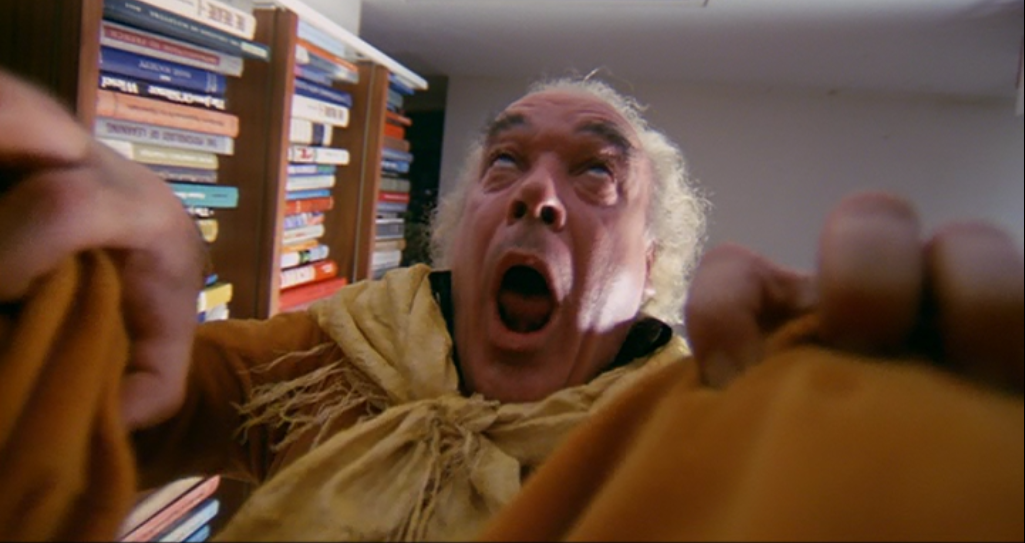

More than anything, the Ludovico Technique gives us the most interesting variation on the face-down-eyes-rolled-up look known as the Kubrick stare. It’s been there since Fear and Desire and Clockwork gives the fullest expression to that, um, expression–even Ludwig van has it. Kubrick begins the film so powerfully with a closeup of Alex’s Kubrick stare, and then the Ludovico technique actually pins Alex’s face into an inverted version of the stare. (This is not an easy thing to watch if you’re sensitive to eye trauma.) Any visit to a poster store will show that these are the two most iconic images from the movie. Magee does a full horror movie variation on it when he realizes Alex is the man who paralyzed him and raped his wife; the horror isn’t just in the expression, it’s in the cut to it when Alex sings “Singin’ in the Rain.” scb0212 noted that The Killing was the beginning of Kubrick’s fascination with grotesque masks, and he never used that more than here.

As Alex, Malcolm MacDowell has to be more than a series of masks; he has to hold this film together as much as James Mason did Lolita. Alex is another essentially aristocratic, entitled character, and his voiceovers have even more third-person self-regard than Humbert Humbert’s. He does well, and he’s a remarkably physical actor, throwing himself into every situation (I can think of no higher compliment for his performance than to note that his last scene of being fed got copied by The Simpsons), but there’s something missing, something not fully realized. He’s never as sympathetic as Kirk Douglas or as evil as George Macready or as funny as Peter Sellers, and the movie really needs him to be all three to work. A good point of comparison to McDowell’s Alex is the work of Matthew Rhys and Jonathan Rhys-Meyers in Julie Taymor’s Titus, another highly stylized, stagy film. Rhys and Rhys-Meyers also played feral, lethal young ‘uns, but they both showed how much their lethality was bound up with that youth, and that made them both horrific and sympathetic.

I can see that McDowell’s performance makes sense as a man who isn’t really sympathetic or evil, but what makes A Clockwork Orange work as an argument weakens it as a movie. Clockwork manages to be both frenetic and flat, because we see the same things going on in all parts of society and all scenes of the film. The droogs have just as much rules and backstabbing as the greater political society; we see that in the attempted coup against Alex at the beginning, in that two of his droogs wind up as cops, and in the Minister’s speech to Alex at the end. Society’s violence to the mind matches the droogs’ violence on the body. Kubrick and Burgess go one step past Max Weber, in that here the State has not only appropriated violence, it’s appropriated the crazy: everyone, be they droog, bureaucrat, family, victim, or killer is stylized into caricature.

Those caricatures resemble each other too much to be interesting, though. Especially compared to Strangelove, you can see the problem. Where Strangelove had such a variety of crazy people, really everyone here plays more aggressive and grotesque variations on Col. Bat. Guano: everyone knows only what they’re told and they have to follow the rules. Clockwork‘s mania feels so forced and even sterile compared to the goofiness and strangeness of Strangelove, or even compared to Peter Sellers’ Clare Quilty. Going back to Titus, Taymor (and Shakespeare) had the Rhys and Rhys-Meyers characters get well and truly owned by Harry Lennix; she showed the difference between their playing at evil and the real thing. For that matter, Monty Python’s Flying Circus (running concurrently with Clockwork) provided a much greater range of caricatures–youthful, bureaucratic, political, British, familial, or any combination of the above–in any given half-hour than Clockwork did. Jumping forward a few decades, American Psycho had a lead character who was into the old ultraviolence (and had his own posse of droogs) but Mary Harron placed him in greater range of types as well. Harron cited Kubrick as one of her influences, but Clockwork doesn’t have anyone like the achingly naturalistic Cara Seymour or Chloe Sevigny in it. I can see the value here as an argument, in that we’re seeing a society where everyone has been processed into becoming identical. It’s just not that funny or dramatically compelling. Starship Troopers had the same problem, in that Verhoeven had to drain the life out of the main characters to make an effective satire.

There’s no question, given all the other movies I’m reminded of, that A Clockwork Orange has been influential. (Even the trailer has been influential; Michael Haneke used it as a model for Funny Games‘ trailer, but at no point does ZORN appear on the screen.) As well as the novel, it’s part of a tradition of satire that goes back to Jonathan Swift and “A Modest Proposal,” but what he does here has been done better by others, and by Kubrick himself–but more on that in the next two films.

Previously: Soundtracking: Kubrick and Ligeti

Next: Barry Lyndon (1975)