Les Blank’s documentaries cover a range of subjects but keep coming back to some fundamental elements, places, and communities: Cajun life in and around Louisiana, the work of artists, everyday life in a variety of settings, and music and cooking everywhere. It’s tricky to talk about what’s unifying in a filmmaker who takes the diversity of humanity as a first principle, but watching a collection of his works (with the best example being the 14-plus film Criterion box set Always for Pleasure) shows a strong vision, even stronger because it’s never really proclaimed, only felt. What binds Blank’s best work together is the feel of tradition, of a past that hasn’t been dissolved by the passage of time.

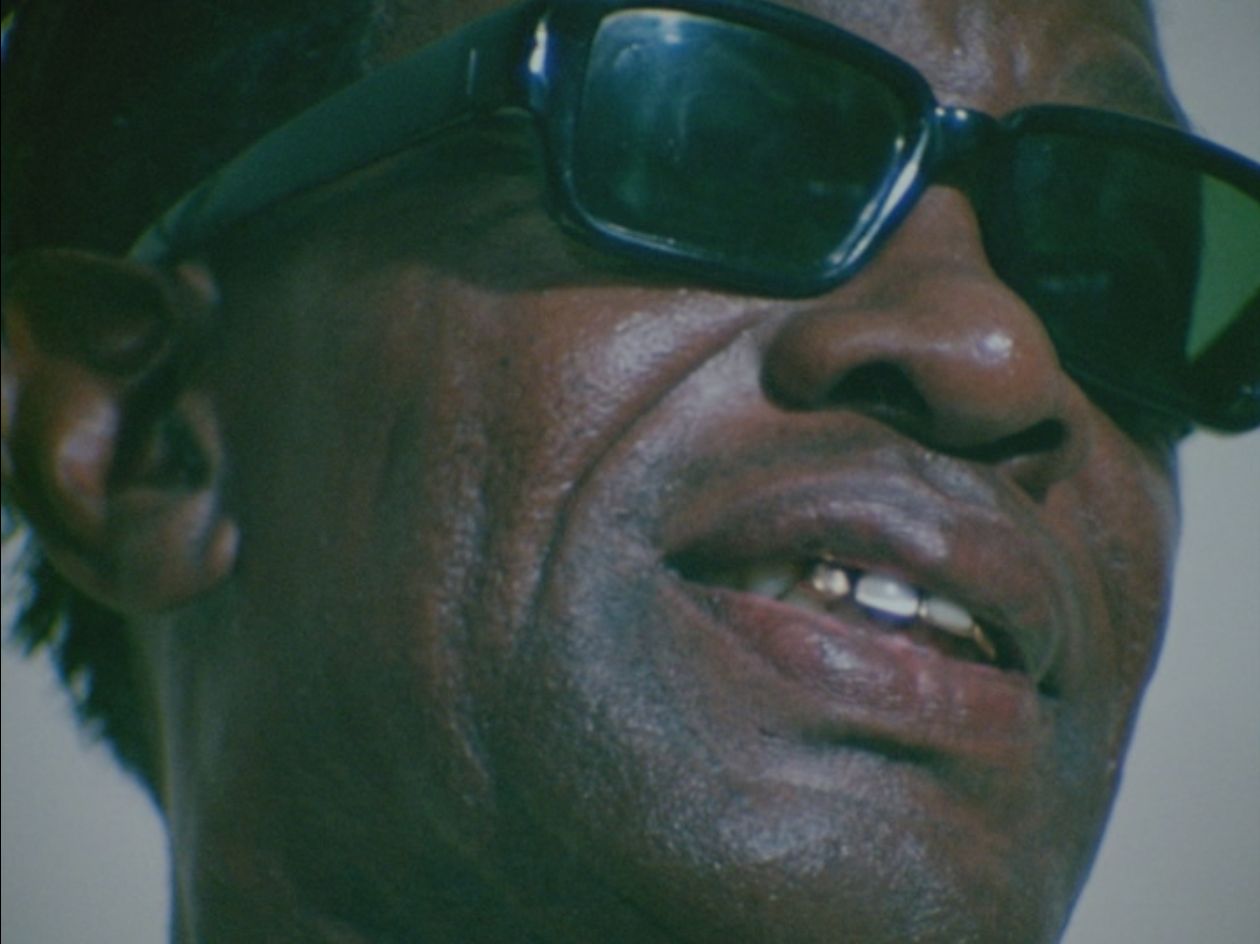

The value of the past first appears in Blank’s choices of subject matter. Several of his films take an artist as a central figure: The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins, A Well Spent Life (about another bluesman, Mance Lipscomb), Hot Pepper (about Clifton Chenier), Sprout Wings and Fly (about fiddler Tommy Jarrell), The Maestro: King of the Cowboy Artists (that would be Gerald Gaxiola), and all of these are artists who have strong ties to tradition and to a community, who unavoidably invoke the past in their work. (Blank taking on a figure of Modernism, someone who consciously rejected tradition, would have been a real challenge for him. I wish he had done a documentary on Elliott Carter.) Other films are directly about the preservation of tradition in the contemporary world: Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers, Yum, Yum, Yum: a Taste of Cajun and Creole Cooking; In Heaven There Is No Beer? That last one is about polka music in the upper Midwest, and remains my favorite Blank. An average-to-good documentarian would teach us a lot about the past just by honestly presenting these subjects, and Blank is one of the best.

It’s not just the subjects and doing the job that matter, though; Blank embeds community and tradition in the images and rhythms of his films, and that takes him from the “very good” to “great” category. Teasing out how he communicates value through style is trickier. Unlike Errol Morris or Werner Herzog, Blank doesn’t make his presence as director known; his creativity can only be understood in how he shapes, edits, and presents his material. These films rarely have any kind of overarching narrative, feeling more like time spent in a place. That absence makes Blank’s editing choices (Maureen Gosling edited most of these films) even more crucial, because the films are never boring. At their best, every cut gives us something new or interesting to see.

One of the structural characteristics of Blank’s best work is that the only speakers–really, the only characters–are from the community he’s filming. He rarely gives the voices of experts, those for whom the community is a subject to study rather than a place to live. Gap-toothed Women is an exception to this (there’s another one I’ll discuss below), because being gap-toothed is an interesting common characteristic but it doesn’t actually create a community. Another defining aspect of Blank’s subjects and speakers is that they never seem to be answering questions, even when we can hear questions asked in the sound. They speak at length about their lives and their worlds, long enough so we can hear the cadences and inflections of their speech as well as their meaning. (Jennie Livingston would use the same strategy, and to the same effect, in Paris Is Burning.) That’s necessary, because their speech doesn’t just convey information, but a sense of their world.

Blank does so much to convey the surfaces and textures of his worlds; he is as sensual a director as Morris is philosophical (epistemological, if you wanna get all technical about it) and Herzog is ecstatic. The sensuality begins in all the kitchens and backyards and riverbanks where Blank’s subjects engaging in the most important activity: cooking and eating. Hannibal gets praised as “food porn,” but as porn, it’s the equivalent of Cinemax–all elegant smooth surfaces and images we’ve been conditioned to accept as delicious. Food in Hannibal is an expression of Hannibal, a man of wealth and taste; food in Blank is just plain yummy-looking. Blank always shows cooking from the earliest step possible (this is practically the plot of Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe), giving us the grinding of the meat, the peeling of shrimp; he gets close to the stickiness, messiness, and colors of cooking and eating, and always shows both as a communal ritual. Hannibal makes you want to find the recipes; Blank makes you hungry. The sensuality extends outward from the kitchen to everything we see. A repeated sequence in Blank’s work is the shot that just watches the landscape or the interior spaces, and observes people moving through them; occasionally he catches them reacting to the camera. He always attends to everyday rituals: conversation, baptism, hog-killing. Again, there’s always attention to how things look, what the surfaces are like; Blank holds shots for longer than necessary to just convey information. He lets us see what things look like. The way that he holds on images like these make his films feel less like narrative and more like a visit to a distinct world.

The sensuality extends outward from the kitchen to everything we see. A repeated sequence in Blank’s work is the shot that just watches the landscape or the interior spaces, and observes people moving through them; occasionally he catches them reacting to the camera. He always attends to everyday rituals: conversation, baptism, hog-killing. Again, there’s always attention to how things look, what the surfaces are like; Blank holds shots for longer than necessary to just convey information. He lets us see what things look like. The way that he holds on images like these make his films feel less like narrative and more like a visit to a distinct world.

Music comes in as another necessary sensual layer in these films. Although there are a lot of great musicians here: Hopkins, Chenier, Lipscomb, so on, we don’t see them perform all that much, if by “peform” we mean “play music for an audience.” There are more rehearsals here than performances. Blank often uses their music on the soundtrack, but he’s much more interested in, for example, Chenier and his brother packing and driving to a performance. What matters is hearing what they have to say, and even more so, seeing their relationship to the community around them. The music becomes one more element of the world, not something that comes from a specific person. Robbie Robertson of the Band said that the South is the only place we’ve been where music seems to come from the air; music has the same feel here. Blank has no interest in the Romantic ideal of the singular artist who brings forth works from his own soul; without ever diminishing the individuality of his subjects, he makes music feel like cooking or conversation, one more tradition passed down through generations.

For better and for worse, politics are not a part of Blank’s films. Maurice Lipscomb of A Well Spent Life spent that life as a sharecropper, and that’s not presented as injustice. For what Blank does, that’s a necessary absence, because treating that life as an injustice would mean to treat it as not ordinary. Sharecropping was part of Lipscomb’s life, of his community’s life, and it always was, and that’s what Blank wants to show us. Change, like politics, isn’t part of these films either. It’s a distinctly modern idea that there’s an obligation to make the world better–according, of course, to the modern definition of better–and it creates the feeling that if you’re not working as a reformer, you’re not a Good Citizen. Conservatism understands change as something that happens organically and slowly, though, not something that Good Citizens can create. Blank’s communities have a value in themselves, not as a symptom of a larger social problem to be cured. (If you consider this the normalization of inequality, that assumes equality is normal.) This can be seen as an abdication of responsibility; it can also be seen as honest.

Blank’s films give to the famous their ordinary lives, and the value of them. Following Clifton Chenier in Hot Pepper, we first see him rehearsing with his brother, and then driving with him; we go from there to meet his family, especially his grandmother. Blank gives us several shots of the wall of photographs of his extended family, and spends time in the small barbeque restaurants and the barbershop of his hometown. (That barbershop is quite the big deal.) In another film, these would be digressions; here, they’re the point. You never see the King of the Zydeco here, only someone living his life, a life that’s about food, family, and music. He’s like anyone else in his community, which is to say he’s the opposite of a famous person. Fame, in our world, means separation from everyone, a kind of sacredness or at least alienation. That’s exactly what Blank never shows; the subjects of Dry Wood, A Well Spent Life, Sprout Wings and Fly, and Lightnin’ Hopkins are all legendary, but you’d never know that from watching the films. Everyone is known but no one is famous. Even The Maestro, maybe the Blank work that’s the most about a single person, situates Gerald Gaxiola in his home and among his audiences. Blank’s lack of interest in fame as a subject may have been what led to the non-release of A Poem Is a Naked Person, about rock musician Leon Russell; in Noel Murray’s review, “a good third” of Poem “consists of local color, shot around Russell’s native Oklahoma”; “rumor has it that a big reason [it] didn’t get distributed back in the 1970s is because Russell didn’t like Blank’s zig-zag style, and. . .he had the power to kill the project.” If Russell was expecting Poem to be about him (the way, say, D. A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back was about Dylan), he had the wrong director.

Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe does indeed have a single subject. It could have been an exploration of fame, but it comes across more as a monologue from Herzog about the potential of films. Again, Blank crafts a narrative here without any overt indications, tracking the day Herzog arrives in Berkeley, prepares and eats his shoe before a screening of Errol Morris’ Gates of Heaven. (Herzog said that if Morris ever completed a film, he’d eat his shoe, and there’s no way the guy who ran full-speed into a cactus wouldn’t make good on that bet.) Herzog, through his manner and openness (he’s never come across as more accessible) implies a community of artists that we don’t have to see to feel. When he says, filmmakers need to create “adequate images. . .a new grammar of images,” it feels like Blank’s mission statement. It’s completely appropriate, even necessary, that it’s not Blank who says it.

The emphasis on communities outside of mainstream America calls up a particular strain of American culture and optimism, that of the New Deal and the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP). Blank’s films can evoke the guides to small cities and villages that the FWP commissioned in the 1930s; they can also evoke, especially in the early films, the photographs of the era that documented the effects of the Dust Bowl, especially the migrant camps. Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother is the most famous of these, and some of Blank’s images have that iconic power but not the distance in time of Lange’s work. He has truly taken an old grammar of images and turned it into something new. The strongest connection to the 1930s comes with the feel of a common culture, the idea that in the absence of wealth and the striving for it, people of different lifeways can connect and find a common humanity. The New Deal, the cornerstone of modern liberalism, was a deeply conservative project, all about the older values of community and work. (Warren Susman makes this argument in Culture as History in great depth.) Perhaps in this way Blank’s truest ancestor is Frank Capra; when he takes a moment towards the end of Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers to step away from the chefs and festivals and watch the real producers of America–the farmworkers–and drops SUPPORT THE PEOPLE WHO GROW THE FOOD WE EAT on the screen, you can feel the heritage.

The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins has that FWP feeling. One of Blank’s earliest films, it’s much-more self-conscious in its artistry, less about a community than what Blank has to say about that community. There’s a repeated shot of Hopkins in silhouette here that tries to make him into an icon, and he alone gets to speak for most of the film. There’s a sequence of shots–portraits, really–of black children that evoke the Walker Evans portfolio that opens Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Blank composes the sequence of photographs of Clifton Chenier’s relatives the same way in Hot Pepper, but the feeling is much different: that film gives you Chenier’s perspective, this film gives you Blank’s perspective. There are also a lot of dissolves, something you don’t see much of in the later films. Somehow dissolves come across as more composed, more artificial, than cuts, and that statement really deserves an essay of its own. (Here’s one.) Blank has a lot of the kind of community shots that define his later works, but for the most part this film is about people in isolation, with Hopkins the most isolated of all. As Blank developed, his films became less about a single person and more about their community, even if they formally had a single subject. Many of those works don’t put the name of who they’re about in the title.

In the Criterion box, the latest film, Sworn to the Drum: a Tribute to Francisco Aguabella stands as another outlier, something that illustrates what Blank does so often by not doing it. In description, this does what so many other of his films do: use someone as a way in to a community and a culture, here the Afro-Cuban drumming world. Yet Blank made the most conventional documentary I’ve ever seen from him: concert footage (the shots of the crowd are the most Blankish), talking heads against uninteresting backgrounds, footage of other films, both fictional and documentary–there are crowd scenes from Cuba from another Blank film, Routes of Rhythm. (I’d rather be watching that.) We don’t see much of family or community here, but we do see celebrities: Bill Graham, Dizzy Gillespie, Carlos Santana, Sheila E. It ends with the information that Aguabella has been recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts, which feels all too conventional a blessing. The last thing we see is Aguabella and a few other performers on an otherwise empty stage, an unusually alienating image for Blank. When Expert John Santos (identified as “Percussionist, Composer, Historian”) explains about the role of drumming in African communities, the difference between this and Blank’s best work becomes clear: this film explains what the other films demonstrate. I came away from Sworn to the Drum having learned something, but not having felt it.

Sworn to the Drum and, to a lesser extent, The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins create a distance between us and its subject that’s unique in Blank’s work. So much of what he does brings us into these communities with old roots; perhaps his most important and affecting accomplishment is a sense of the past without nostalgia or romance. In The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics (one of the most essential conservative works), Christopher Lasch calls nostalgia “the abdication of memory.” Lasch gets that nostalgia is “only superficially opposed” to the idea of progress; in fact, it’s an essential component of progress. No matter how accurately nostalgia portrays the past, no matter how much it romanticizes the past over the present, nostalgia says the past will never come back.

In Blank’s films, the rituals, foods, sounds, and people of the past fill up the frame. There’s nothing dead or gone about them, and there’s nothing special about them either. His camera catches the way past rituals get embodied in people; one detail I particularly love is almost no one ever measures anything when they’re cooking, they just toss in the crayfish or salt or red pepper like they’ve always done it that way, which they have. Those actions, performed through generations without thinking, are what Edmund Burke meant by “prejudices”–knowledge so deep in a people that it didn’t have to be thought about anymore. We see these rituals as part of everyday life, in the dinners and dances and work, not as some kind of separate, specialized, nostalgic festival. Blank’s style of catching rather than staging things further emphasizes this; it matters that he watches the rehearsals and warm-ups and kitchens, because that’s where the past gets enacted unselfconsciously. It also helps that we see so many contemporary, ordinary details, the brand names that are part of our present. (It’s that 7Up sign in the header image that makes it, as Werner would say, adequate.) One of the characters in Yum, Yum, Yum! insists on that point; she’s puzzled why anyone would use anything but the most generic spices. It’s the opposite of the artisanal foods movement, which makes a class of foods a signifier or fetish object for the past. It creates someone else’s tradition as a thing to be sold to the contemporary urban classes.

Among recent works, the first season of True Detective had some of this feeling of the rituals and landscape of the Louisiana past colliding with the present; I wonder if director Cary Joji Fukunaga is a Blank fan. (Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson having lunch at a roadside Vietnamese café feels like it belongs somewhere in the Criterion box.) Unsurprisingly, a lot of Blank’s films are set in Cajun country, where past, present, history, and multiple races all collide and live together, a place where the progressive ideal of assimilation hasn’t happened and possibly never will, where community doesn’t come from the Enlightenment’s abstract idea of common humanity but from the specific, old rituals–cooking, performing, talking, working–that specific people share. Like Paris Is Burning, Blank’s films are demonstrations rather than arguments about the diversity and messiness of people. Writing in The Old, Weird America: the World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (originally and more evocatively titled Invisible Republic), Greil Marcus spent a key early chapter on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. This six-record set was the founding document of the American folk revival of the 1960s, and as such it’s one of our most necessary cultural artifacts. Marcus described the songs of the Anthology as making up its own community. He called it Smithville,

Writing in The Old, Weird America: the World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (originally and more evocatively titled Invisible Republic), Greil Marcus spent a key early chapter on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. This six-record set was the founding document of the American folk revival of the 1960s, and as such it’s one of our most necessary cultural artifacts. Marcus described the songs of the Anthology as making up its own community. He called it Smithville,

a mystical body of the republic, a kind of public secret: a declaration of what sort of wishes and fears lie behind any public act, a declaration of a weird but clearly recognizable America within the America of the exercise of institutional majoritarian power.

(He named the community defined by the Basement Tapes Kill Devil Hills, and Todd Haynes renamed it Riddle and portrayed it in the Richard Gere section of I’m Not There.) It’s an elegant critical move, giving just enough descriptive unity to the world Smith created or found and embedding it in something we can all imagine. Blank, an artist who was as much a curator of America as Harry Smith, deserves the same treatment. The community defined by Blank’s documentaries would of course be Blank City, apparently a few hours upriver from New Orleans but also just down the road from the Bay Area.

It’s not like Smithville. There, the “ruling question of public life [was] how people plumb their souls and then present their discoveries, their true selves, to others.” That question doesn’t matter nearly as much in Blank City as “what’s for dinner?” Identity, that value so prized in the Enlightenment, the value that has been corrupted and commodified in our world as celebrity, means separateness, and Blank City is the home of communities and families. What’s deep here isn’t the soul but the history; what’s most important isn’t the legendary event (Smithville has so many of them) but the everyday. Creativity doesn’t come from individuals but from everyone, and it’s happening all the time; even gossip is a creative act in Blank City. Someone’s always cooking here, someone’s always playing music; no one is wealthy, no one is a stranger, and no one goes hungry. The brand names, clothing, and colors all tell us that this city exists in our world, and all the actions are the same as hundreds of years ago.

As a name, take “Blank City” in the same way Richard Hell meant his album title Blank Generation; he said it should be read as “________ Generation,” and you fill in the blank however you like. (A poster for The Blank Generation appears behind Werner Herzog’s head after he eats his shoe. Watch for it.) Blank gives the world so many different cultures, people, and histories in his films, but what really counts is the way he gives you your own history. He takes what would be exotic and makes it familiar, everyday; the filmmaker who makes Werner Herzog seem like the guy sitting with you at the bar won’t be thrown by anything. Peter van der Merwe wrote “the biggest danger lies in underestimating the strangeness of these cultures”; Blank’s alchemy makes these cultures strange but not one bit distant, as unique and accessible as your own. In cutting itself off from the past, the modern world deprived itself of that strangeness; Max Weber called this process “the disenchantment of the world.” Blank doesn’t underestimate the strangeness of anything. He shows it from within, as ordinary life, and that makes you feel the strangeness in the ordinary. After watching Blank’s films, you start imagining the film he could’ve made about your community; all great filmmakers give you their perception, in the same way that all great novelists give you their consciousness. After watching, you can look at your own day and see all the rituals and community and history that are there at every moment. The past isn’t a foreign country anymore. It’s home.