It starts with a warning. The bass is a jabbing finger, a series of threats, strings rattling with anticipation. And then the riff begins, the sound of a stocky, powerful person stalking your way, getting closer. Drums rustle and a trombone enters in ominous counterpoint, its long unhurried reach holding you in place as the piano’s low chords bar the door. The riff is no longer approaching, it is here and pummeling as the drum fill slaps off and then back into the beat, a crisp bludgeoning swing as saxophone squalls over the trombone and piano, five men making a racket that sounds sounds like it’s coming from a gang, a mob, an army of pissed-off people with violence on their mind, and there’s still 10 minutes to go.

It is Charles Mingus’ centennial this year (technically two weeks ago). Mingus was a sideman, a bandleader, a composer, one of the great bassists of the 20th century, a musician who once had his psychiatrist write the liner notes for his latest album. He was a man of many and contradictory parts and the 1993 compilation 13 Pictures recognizes this, showing facets of the man instead of attempting to provide a complete portrait. There’s the ambitious (and anxious) composition “Half-Mast Inhibition,” written when Mingus was 18, and “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion,” a massive yet lesser-known piece from his final years in the 1970s, before he died from ALS. There’s the raucous “Better Get Hit In Yo’ Soul” and the sorrowful and gorgeous “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” probably his most famous pieces, and “Wig Wise,” Mingus playing one of his idol Duke Ellington’s tunes. And then there is “Haitian Fight Song,” which refers to the Haitian Revolution of the 19th Century and which grabbed and shook me the moment I heard it more than 20 years ago, after my bass teacher handed me 13 Pictures and told me to check this guy out.

The band pulls back after the beatdown of the opening but maintains a simmering intensity and clarity – Mingus and his collaborators can be knotty and obtuse elsewhere but the playing here is direct and easy for a novice listener to follow. Jimmy Knepper’s trombone punches with precision and then flings a fury of jabs as the song moves into double time. Wade Legge’s piano is cooler, laying back, and Shafi Hadi’s saxophone snakes and weaves before he too lets loose in double time before slowing down for some final, confident shots. Underneath all of this drummer Dannie Richmond is pushing and punching, his toms and snare have a slight echo that emphasizes not a hollow boom but the sound of a heavy bag thwacked – he’s an enormously underrated drummer who was entirely keyed into Mingus at all times, including the rolling waves of his bass under the soloists here.

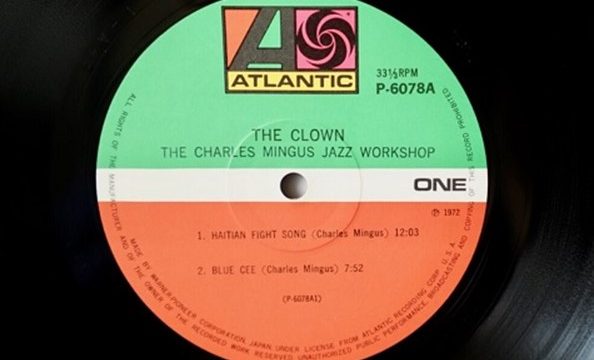

And then Mingus himself takes over, the low end more prominent than it was in his opening solo but his plucking ruthless and his tone clear. He floats like a butterfly and stings like a hornet, coming in off rhythm and letting the listener move into spaces he is not before dropping the hammer – THUMP, THUMP THUMP. But he’s still melodic in his phrasing, in his runs and as they fit into a larger whole, unified in anger. “My solo in it is a deeply concentrated one. I can’t play it right unless I’m thinking about prejudice and hate and persecution, and how unfair it is,” Mingus says of “Haitian Fight Song” in the liner notes to The Clown, the 1957 album where the most famous version appears. “There’s sadness and cries in it, but also determination. And it usually ends with my feeling: ‘I told them! I hope somebody heard me.’” Other versions, like the full-bore large band version “II B.S.”, have even more punch but they don’t have the power of what Mingus plays here.

The solo leads back into a reprise of the opening, Mingus’ riff calling the band together for one last blast of a beatdown before slowing to a coda that is exhausted but not defeated. I need to take a deep breath when it’s over but it’s because I’m exhilarated. And then I want to hear it again. Mingus got a lot of use out of “Haitian Fight Song” and reworked it numerous times (and frequently slipped its horn riff into other compositions), this website does a great job tracking the various versions and samples. The opening bassline, unresolved, is fantastically propulsive in the third verse of Gang Starr’s “I’m The Man.” There are less pleasing uses, though. A Volkswagen commercial uses “II B.S.” to shill Jettas, and Cameron Crowe infamously makes the song a goof in Jerry Maguire, a tune Tom Cruise’s wacky jazzbo neighbor puts on a mix CD for sexy times and that Cruise and Renee Zwelleger laugh off – what is this noise? Somehow I doubt Crowe would’ve done a gag like that with “Fight The Power” or “Fortunate Son,” two of the extremely small number of songs that can match the ferocity of “Haitian Fight Song,” an intensity that no one would ever mistake for anything else. It makes me mad.

But overall that’s a pretty minor thing to be mad about. There is much worse out there, as Mingus knew and wrote about again and again. And you can get too angry. Mingus sometimes hurt people when his wrath took over. During an argument a few years after “Haitian Fight Song” was recorded, he punched Knepper in the face and destroyed his ability to play trombone for two years (the two eventually reconciled a decade later). In an insightful write-up of 13 Pictures, the online magazine Elsewhere quotes writer Geoff Dyer’s impressionistic imagining of Mingus: “His rage never left him. Even when he was calm the pilot light of his anger was blinking away, ready to erupt at any moment. Even when he was quiet some part of his head was yelling. He didn’t know why he was the way he was, but he knew he had to be that way and no other. His rage was a form of energy, a fire sweeping through him.” “Haitian Fight Song” is a fire that jumps into you. It’s burned for more than 50 years and its flame is undimmed, ready to fuel any fight.