The Big Trail was the beginning and the end of a lot of things. It was John Wayne’s first starring role, and it tanked his career so hard that no one questioned John Ford’s often-told story of “discovering” him on the set of Stagecoach nine years later. It brought the Western into the sound era and promptly killed that off too. And decades before Cinemascope, it was a 70mm widescreen epic that so few theaters were willing to buy the equipment to show that it lost millions of dollars and killed off the entire format.

In other words, this is, in My Year of Flops terms, a true fiasco. Estimates place the budget anywhere from one to two and a half million, or almost 40 million in today’s money. Most writeups like to detail where all that money went, and far be it from me to break with tradition, because it’s really something: 20,000 extras, 1,800 heads of cattle, 1,400 horses, 500 buffalo, and 185 covered wagons. No wonder audiences didn’t come to see the cropped-for-35mm version most theaters showed — you couldn’t see half of it.

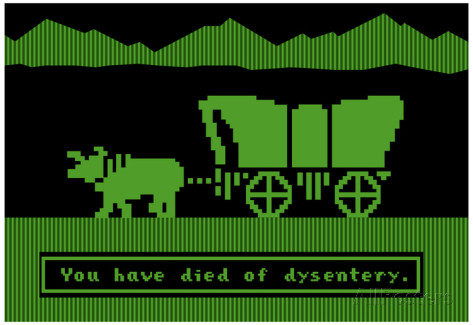

Director Raoul Walsh seemed to think the best way to film his story of pioneers was to haul all this across the country himself, all 4,300 miles of it. And don’t think they had it too much easier than the historical figures whose path they followed. If John Wayne doesn’t look like the beefy, burly figure we all know, maybe that’s because he lost twenty pounds to dysentery. Yes…

I can’t find the exact box office numbers, but I can tell you that investment didn’t pay off. How could it? Watching The Big Trail, I can’t say it was all worth it, exactly, because there’s no doubt it was an absolutely miserable experience, and it’s hard to believe it didn’t straight-up kill somebody. But it’s harder not to be awestruck watching it.

Seeing the pioneers steer their elephantine wagons across a narrow pass reminded me of Aguirre: The Wrath of God. But as it continued, it became obvious I as watching the precursor to Werner Herzog’s other Amazon epic — Fitzcarraldo, where the crew filmed a man hauling a cruise ship up a mountain by actually fucking hauling a cruise ship up a fucking mountain, as documented in The Burden of Dreams.

That’s Walsh’s approach to The Big Trail. When you see the pioneers lowering their wagons off a sheer cliff by enormous pulleys, many of them breaking along the sides, their carcasses littering the cliff face, you know they really did lower those fucking wagons. When you see hundreds of humans, horses, and cattle crossing a deep river, babies crying, some of the cows confusedly drifting away, you know they really did cross that fucking river, in violation of all rules of childcare and animal safety. And as if that wasn’t enough, they did a lot of that six times — once for the 70mm version, once for the 35mm, and again for the French, German, Italian, and Spanish versions that Hollywood demanded for export in the days before dubbing.

The format dictates the content. You really believe the scale of the world these characters live in and the undertaking they’ve set for themselves, both in the fictional story and the reality of bringing it to the screen. Jacques Tati won universal praise for using the widescreen frame in Playtime to create a movie where you could see something happen anywhere you look, but Walsh beat him to it by almost forty years.

At a time when filmmakers were retreating to controllable stagebound environments, Walsh goes outside to capture the real world in all its grandeur. When most filmmakers were struggling to make dynamic movies with the addition of bulky sound equipment, Walsh was thriving with even bulkier and more untested 75mm cameras. A lot of the most spectacular images are the result of the camera’s good fortune to be pointing at spectacular things, of course. But look at the Cheyennes’ attack on the wagon train. There’s complicated shots looking out from between the spokes of the wagon wheels, and others where the horses seem to trample over the camera. But the most impressive shots got my attention precisely because they didn’t get my attention, scenes where the actors seem to remain motionless in the frame as they ride across the prairie thanks to tracking shots so perfect they’re invisible.

That’s not to say Walsh and his crew didn’t have trouble adjusting to sound too. Most of the dialogue is, for want of a better word, hollered so the actors can be heard over the roar of all those wagons, horses, cows, etc. and get picked up by the mics that had to be hidden well from the camera’s omniscient view. But that doesn’t mean The Big Trail is wanting for great performances. As the trail guide Breck Coleman, John Wayne occasionally shows off his inexperience — there’s some hilariously big, wooden gestures to punctuate his dramatic dialogue — but he’s also much more relaxed and likable than in his more famous, mannered performances. Marguerite Churchill gets a seriously underwritten love story with him, but she sells the fuck out of it.

Best of all is Tyrone Power Sr. as our villain, Red Flack. Under the main plot of the wagon train’s journey west lies a grim, fatalistic thread of him and Coleman plotting against each other. Coleman originally passes up the job with the wagon train to take care of his own vendetta against the man who killed his friend Ben. We never see Ben or learn the nature of their relationship, but the ice-cold rage in Wayne’s eyes says all we need to know. He learns Flack’s responsible and joins the wagon train with him.

Wayne accurately describes Flack as a “he-grizzly.” Power plays him as the epitome of a vanished character type, the “heavy,” a huge, burly, beary baritone of a man. Power ratchets the character up to almost cartoonish archetypicality — he’s like a human incarnation of Mickey Mouse’s Pete or Popeye’s Bluto. But instead of making him laughable, it only makes him more of a credible threat. And it makes him a wonderful pair with Ian Keith as his perfect opposite, a genteel Southern gambler, what Steven Spielberg calls the “champagne villain.”

But there’s always going to be an imperialistic elephant in the room with any story like this. Ironically, Walsh lived with and advocated for American Indians for much of his life. Maybe that’s why at first The Big Trail seems to present a whitewashed version of manifest destiny that’s, if anything, even more insidious. Breck Coleman describes himself as a great friend to the Indians, and the wagon train picks up some nameless Pawnee guides to help them to the coast. (In reality, 1930 was so close to the frontier days it recreates that the crew really did need Indian guides to find their way, and supporting player Charles Stevens claimed to be Geronimo’s grandson.)

Coleman’s even friends with the Cheyenne chief Black Elk, who agrees to let the wagons pass through his lands. (He’s introduced in a hilarious scene where his hundreds-strong war party apparently sneaks up on the wagon train somehow.) In other words, this is revisionist history where western expansion came and went without anyone getting hurt.

But the truth can’t help rearing its ugly head. Churchill gets some skin-crawling lines blowing up at the “savages” tittering over her and Wayne’s love affair. And then the mask of civility slips off. We get a full-blown Indian Attack Sequence, and the Cheyenne aren’t treated any differently than the natural obstacles the pioneers face. The movie doesn’t seem to give a thought to why they might be attacking. They’re simply a hostile, outside force, without any consideration of the reality that it’s the movies’ heroes who are the vanguard of an invading force that will eventually wipe the Cheyenne out.

In The Big Trail, as in most attempts to retell it, the colonization of the West is unambiguously heroic, as explained in many fawning title cards. And yet, for all the horror at the heart of its story, Walsh’s telling of it is never less than awe-inspiring.