Monuments topple as we attempt to separate the laudable from the merely memorable! The movies are where we can preserve, change, examine, and celebrate culture. And the debate lies in which of these things we’re doing and which we can be doing better.

Thanks to Rosy Fingers for contributing this week, may he only repeat the best parts of history. Please send articles in the next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post and discuss articles from the past week below, and have a Happy Friday.

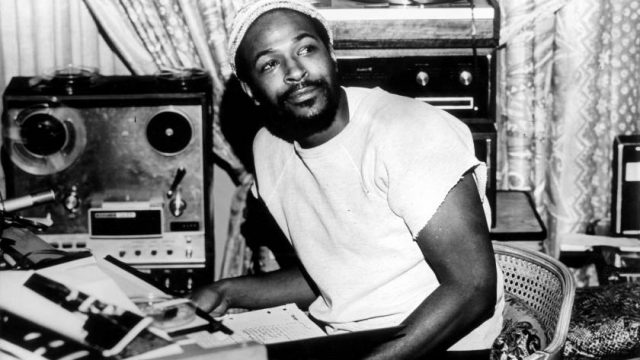

As Spike Lee’s Da Five Bloods makes its debut on Netflix, the LA Times‘s Mikael Wood sees it as another notch in the ongoing cultural legacy of Marvin Gaye’s album “What’s Going On”:

The style Gaye developed for “What’s Going On” — which he produced himself, much of it in Detroit over a single 10-day stretch — was lush but mournful, peppered with Latin percussion and lightly gilded with strings played by members of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. […] Vocally, Gaye “finally learned how to sing” on “What’s Going On,” he told biographer David Ritz. “I’d been studying the microphone for a dozen years, and suddenly I saw what I’d been doing wrong. I’d been singing too loud.”

A double entry at Vulture. Mark Harris makes the case for “problematic pop culture” in light of HBO Max’s decisions to remove the film from its platform, then return it to the platform with a warning…

In a way, putting a warning label on Gone With the Wind will, I fear, be used as an excuse not to explore any of these questions — the end of a conversation rather than the beginning of a more complex one about whether we want entertainment corporations to serve as custodians of cinema history, or as (be careful what you wish for) active curators of it. (We may be just one home screen away from “Other Movies in the Cultural Doghouse You Might Enjoy.”)

…which segues into a reprint of Angelica Jade Bastién’s continually relevant essay about cinematic monuments to the Confederacy from 2017:

Some have argued for Gone With the Wind to be viewed a Confederate monument, and others against. My position skews more toward the latter camp: Whereas these monuments have one message — to celebrate and uphold a painful time in American history, whose scars linger to this day — a film, especially one with so many influences as Gone With the Wind, rarely holds a single message.

Marlow Stern at The Daily Beast investigates how the rabble-rousing Texas studio Cinestate kept producer Adam Donaghey employed until his recent arrest for sexual assault, even though he had a well-known reputation in the state for harassment:

When Cinestate joined forces with Donaghey in 2017, handing him producing duties on a number of its genre films—The Standoff at Sparrow Creek, VFW and Satanic Panic among them—it was met with a raised eyebrow by many in the Texas film scene, who were well aware of Donaghey’s reputation as a serial predator. “The first time I was ever on set I was warned about Adam Donaghey,” a female filmmaker tells me. “I was told he was the Harvey Weinstein of Dallas.”

And finally, Zach Vasquez explores the late Stuart Gorden’s often overlooked American Trilogy including King of the Ants, Edmond, and Stuck:

Even at the height of his success, Gordon remained a cult figure, so this period of his career tends to get overlooked by gore hounds and genre aficionados (to say nothing of square audiences), even though the films themselves are entirely of a piece with his more notorious efforts, featuring some of the most disturbing and stomach churningly visceral imagery and ideas found throughout his filmography. Considering said filmography includes [multiple descriptions redacted] that’s saying something.