“For those who came in late…”

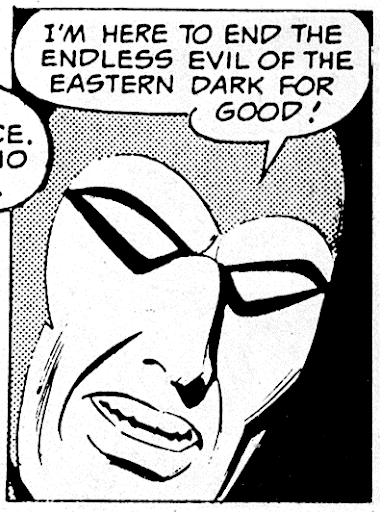

Across the dark realm of the Orient exists a legend of a white man. For more than four hundred years this legend has been spoken in furtive whispers from the unexplored depths of the jungle to the desert plains. This legend inspires reverence within the native tribes; terror amongst pirates, villains, and roughnecks alike. He cannot die, they say… His anger is terrible to behold… His justice is swift… His strength is that of ten tigers… He is the Phantom, though he is known by many names: The Ghost Who Walks, The Man Who Cannot Die, The Guardian of the Eastern Dark.

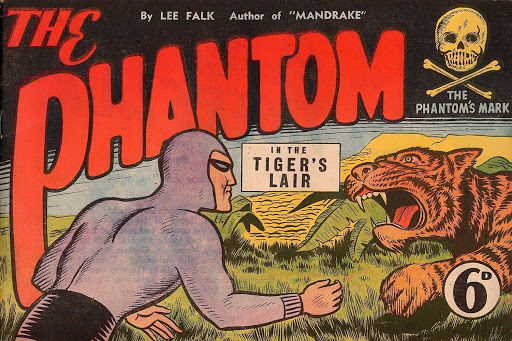

Published since 1936, the Phantom’s adventures in Oriental justice continue to be read worldwide (though he seems to be particularly popular in Australia and Scandinavia). The Phantom is a prototypical superhero – he’s the original masked avenger clad in skin-tight bodysuit – who lives by a sworn oath “to devote my life to the destruction of all forms of piracy, greed and cruelty.” Oriental evildoers beware, for the Phantom is Law, and his authority is limitless. He is both an instrument of rule and a figure of colonial morality: colonialism personified. In Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the “insolent black” boy declared, “Mistah Kurtz – he dead.” But the boy spoke too soon. Kurtz lives on in the form of the Ghost Who Walks.

Of course, the Phantom is not immortal, nor a ghost. In fact, he is not even vaguely supernatural. He is just a man. The current Phantom (from 1936 to present) is the twenty-first descendant in a four-hundred-year-old dynasty. The Phantom legend begins with a sailor washing ashore on a remote beach in Bengal, the solitary survivor of a pirate raid on his sea-captain father’s merchant ship. Nursed back to health by the friendly Bandar, the “pygmy poison people,” the man swore the “Oath of the Skull” on his dead father’s remains and became the first Phantom.

From that time on, the Phantom’s law has ruled his territory. He rules by intelligence, strength and discipline. Choosing to stay with the Bandar in the Deep Woods, the Phantom made his home in the Skull Cave, from where he acts as a self-appointed colonial administrator: holding council, lording it over the Bandar, and venturing out to dispense his violent justice and retribution.

The Skull Cave is a monument to his mission. Through the cave’s gaping mouth lies the cavernous Throne Room, a vast hall festooned with flaming torches and dominated by the imposing Skull Throne of the Phantom. Beyond this chamber lies the Minor Treasure Room, a collected fortune in piles of gold and jewels, and the Major Treasure Room, packed with relics of immense (Western) cultural value, including the sword Excalibur, the original hand-written manuscript of Hamlet, and Homer’s lyre. Further still, and we come to the Crypt, containing the tombs of the Phantom’s twenty predecessors, and the Chronicles Room, where the adventures of the ancestral Phantoms have been recorded for posterity. The contents of the Skull Cave manifest the Phantom’s immense wealth generated through centuries of adventurous exploitation.

“The Guardian of the Eastern Dark”

The Phantom’s territory is a kind of imaginary Orient. Although the Phantom was originally said to inhabit the Indian region of Bengal, following World War II his location shifted to the mythical country of Bangalla. An ill-defined, geomorphous space, Bangalla is an Oriental hybrid nation that seems to shift from Indonesia to Asia to Africa as the narrative warrants. It’s a nation of nomadic slavers, big game hunters, primitive tribes and tyrannical, medievalist royalty. In recent decades, Bangalla’s location has become more fixed, being located in central (though sometimes coastal) Africa.

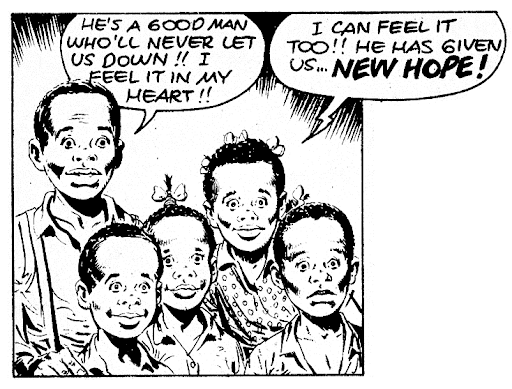

The center of The Phantom’s world, the Deep Woods, is peopled with tribal villages of superstitious, loincloth-wearing natives. The Phantom’s primary duty is to guard these noble, though gullible, savages from the corrupting influences of the modern world. His colonial rule forbids the intrusion of poachers, drug dealers, bandits and urbanized natives into the simple world of the tribes. The Phantom’s protection allows the natives to maintain happy and carefree lives in their tribal villages, as long as they never leave.

But even the Phantom’s protection could not prevent the great tide of modernity from engulfing Bangalla. The colonialist ideology of Phantom comics must to some extent keep pace with political discourse lest the comic be seen as an offensive and shameful throwback. In recent decades, the Phantom has seen his absolute colonial rule gradually dismantled while Bangalla has transformed into a modern nation-state. What was once a dark and dangerous landscape has developed into an enlightened and liberal democracy, complete with modern metropolises and a popularly elected, humanitarian president.

“There are occasions when the phantom leaves the jungle and walks the city streets as an ordinary man…” – Old jungle saying

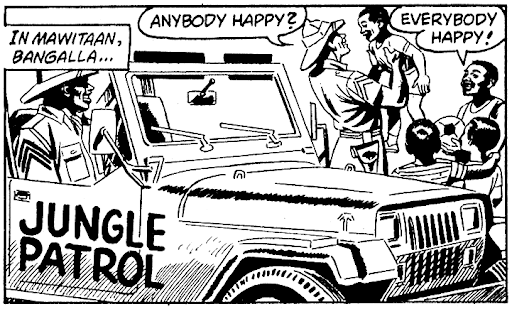

Bangalla’s capital city, Mawitaan, is the very model of a prosperous, modern metropolis. A coastal city sprawling around its industrial sea-port, Mawitaan is a dynamic urban center of crowded streets, sleazy bars, skyscrapers and Bangalla’s Presidential Palace. But it was not always such. Mawitaan has developed and grown with the times.

For many years after 1936, the city was known as Morristown, a small colonial settlement where travellers could purchase supplies or hire jungle guides and suchlike. And drink, of course. It was the kind of frontier town where pack-mules stood tethered out the front of saloons. Although bar fights were common enough, briny sailors on shore leave could often be seen seated alongside well-scrubbed colonial officers in relative peace. In those days of colonial rule, Bangalla was officially administrated, “with an iron hand,” by the white governor from his office in Morristown. Crime was rare in colonial Morristown. The town’s population were benign settlers. Any major crime was usually the result of a notorious gang of mobsters or pirates visiting town to pull some kind of one-off jewel heist or bank robbery. These were the times when the Phantom would don his full-length tweed coat, hat and sunglasses, and venture into the city as Mr. Walker (for the Ghost Who Walks) on a mission to reinstate order in the colony.

Over the decades Morristown slowly grew, affecting more of an urban environment as the process of decolonization was subtly undertaken. Morristown was renamed Mawitaan, instigating an ideological struggle between opposing factions of Phantom writers; those who accepted the new, Africanized appellation and those who insisted on using the Morristown title. This struggle continues to the present, with the city still bearing its colonial name in some Phantom comics. During the late ’60s to mid ’70s, it became apparent that Bangalla’s colonial administration had simply departed, leaving the nation’s governance in the hands of its people. All of a sudden, and without fanfare, Bangalla was a democratic nation-state with an indigenous President and a Presidential Palace in central Mawitaan.

Along with all this modern progress, decolonization and democracy, come the attendant problems of metropolitan life. Modern Mawitaan is infested with crime and poverty — drug dealing, gang violence, homelessness, organized crime, teenagers — most of it from within the urban population. Mr. Walker cannot restore order to the chaos of the modern city; the task is impossible. The Phantom knows the city is a lost cause. Whereas Morristown was an innocent settlement of virtue true, post-colonial Mawitaan has become a site of corruption.

“No man can refuse the voice of the Phantom”

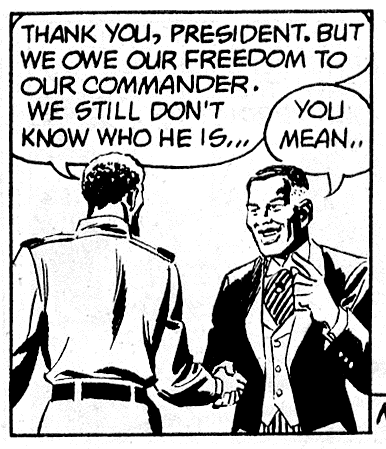

The Phantom’s friend Dr. Lamanda Luaga is the first President of the Republic of Bangalla. A gracious, educated, and well-mannered man, Luaga was swept into the presidency on the basis of his humanitarian works. He governs his native Bangalla with absolute integrity and benevolence, never hesitating to speak or act upon what he knows to be right, whether it’s aid for the suffering Rhodians, United Nations-sponsored crisis interventions, or refusing to approve a licence for oil-drilling in the deep jungle because it “could endanger the jungle animals.”

President Luaga is an honourable leader and a protective father figure, and he has just enough class to look good in his tailored suits. But aside from his admirable character traits, it is the Western education Luaga received that qualifies him to lead Bangalla. He understands modern democracy because he is himself a thoroughly modern citizen, and he knows that the actual source of his power is the colonial legacy that props him up. Frantz Fanon would be shaking his head. The Phantom rests assured that Luaga will never challenge Phantom’s self-appointed status as the lawmaker. Luaga is well aware of who is the actual authority over Bangalla, and it is not the post-colonial President.

So the Phantom’s ultimate superpower is administrative justice and discipline. This aspect of his character is represented through the machinations of the Jungle Patrol, a “paramilitary peacekeeping squad” organised three hundred years ago by the sixth Phantom. The Jungle Patrol polices the landscape with a range spanning five countries. Each year, thousands apply from all over the world to join the famous squad, but a mere ten are selected, ensuring that the Jungle Patrol remains “the most elite force on Earth.” The troops of the Jungle Patrol are, to a man (they are all men), the most downright honourable, decent and clean-cut chaps one could ever hope to cross paths with. Like good boy scouts, they are devoted to taming the wilderness, and they go about their mission with a diligent and efficient manner.

The Phantom acts as hidden Commander of the Jungle Patrol, issuing his directives through a complex network of locked safes and secret tunnels, although sometimes he does telephone, which seems easier. None of the Jungle Patrol has any idea who their unseen Commander is, not even Colonel Worubu, the Phantom’s second-in-command and the Jungle Patrol’s operative director.

The first appearance of the Jungle Patrol in Phantom comics came in 1952 and it’s easy to see the Jungle Patrol as being a quasi-United Nations peacekeeping force. Indeed, the Phantom’s publishing company has said that the Phantom himself “has increasingly come to function as something of a United Nations troubleshooter-at-large.” Unconstrained by national borders, the Jungle Patrol has the power and, it is implied, the popular consent to impose order on the land. Like the United Nations peacekeepers, or the Phantom’s individual heroics, the Jungle Patrol functions on the myth of unbiased intervention, of disinterested violence.

“The horror! The horror!”

The Phantom has embodied the colonial spirit for over eighty years now and still he walks the imaginary pathways of the Orient. His story has survived the worldwide dismantling of colonial powers. He has stoically borne the encroachment of modernity into his exotic realm while he patiently nurtured the myth of the adventurist warrior. The Phantom will endure until the colonialist dream of absolute rule is truly diminished. He knows that his power is righteous. He knows… And in the meantime, he will manage. The Phantom is good at adapting.

So the Phantom now wears the mantle of peacekeeper, preaching the discourse of human rights. Which works for the character. That’s what the mask is for. The Man Who Cannot Die has time to kill. And as he abides, he silently reiterates, “Exterminate all the brutes!”