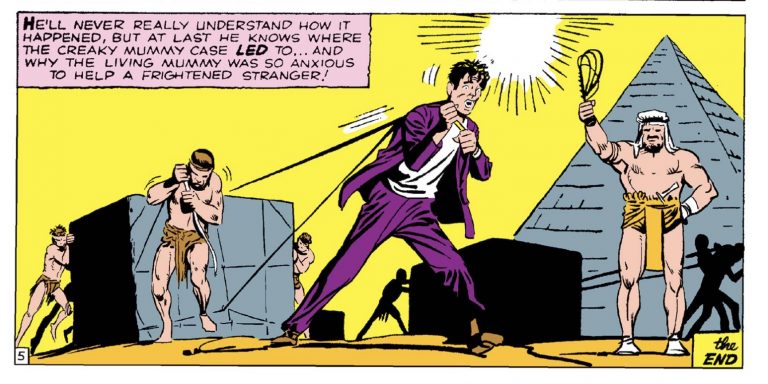

Amazing Fantasy 15 was the final issue of the Marvel anthology series Amazing Adult Fantasy, which had also been called Amazing Adventures. It more or less keeps the format it had throughout the series: short stories with a sci-fi or fantastical premise and an ironic twist, typically in the final panel.

For instance, the short story “Man in the Mummy Case” opens with a criminal fleeing from the police. He dives through a window of a museum, where he encounters a mummy. The mummy helpfully offers to hide the crook from the police in the mummy’s sarcophagus. The criminal of course is scared of being turned into a mummy, but the mummy helpfully (and honestly) reassures him that he won’t be turned into a mummy, that he’ll have plenty of air to breathe, and that the mummy will open the case when the cops are gone. The police enter the museum and open the sarcophagus, but the sarcophagus is empty! Somehow, through some arcane Egyptian magic, the man has been hidden from the police, and he definitely will not be caught. How did the mummy save the crook from the cops?

So this is the context in which Spider-Man first appears. He was originally just a one-shot character in an anthology series – your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man wouldn’t even show up again in print for seven months after his debut. (The editorial page anticipated that there’d be more Spider-Man in future issues of Amazing Fantasy, but there were no future issues).

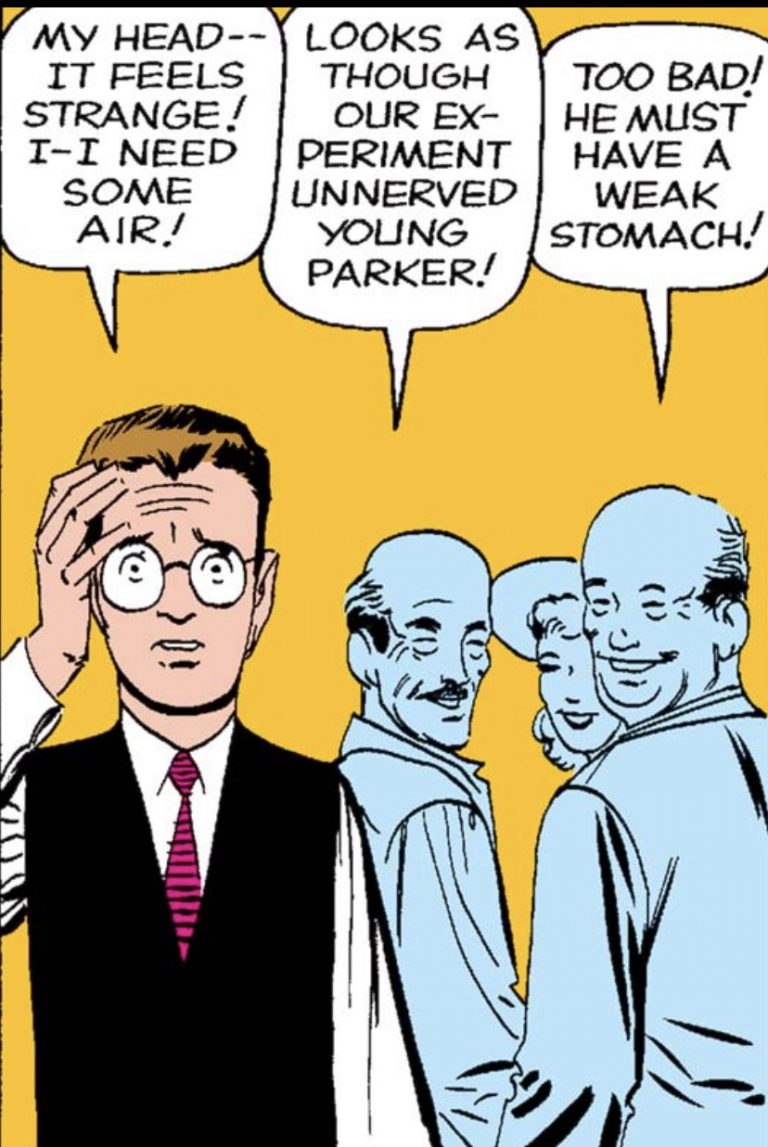

As a one-shot – setting aside everything that comes later, setting aside the rogues’ gallery, Gwen Stacy, Mary Jane Watson, J. Jonah Jameson, and Spider-Ham, – it’s a great, economically told short story. We’re introduced to Peter Parker being excluded from a school dance because “that bookworm wouldn’t know a cha-cha from a waltz,” which I’m sure was an eviscerating insult in 1962. He’s being raised by his doting Uncle Ben and Aunt May. He’s good at school, but not popular. When everyone else is going out to have fun, Peter is going to a science exhibit by himself. Here, we see the first real hint of an aggrieved Parker that could turn selfish, instead of heroic, with Parker muttering to himself between sobs that “one day they’ll be sorry they laughed at me.”

At the science exhibit, of course, he gets bitten by the radioactive spider that gives him his powers. Perhaps more importantly, after he’s bitten the scientists running the exhibit gently mock Peter, saying “Looks as though our experiment unnerved young Parker” and “too bad, he must have a weak stomach.” Ditko’s art relishes in the scientists’ mockery. Just look at those smug, grinning jerks:

Unlike in the Sam Raimi movie, Peter does not enter the wrestling contest because he needs money. He enters it for fun. He asks himself “what [he] can do with this unbelievable ability which fate has given [him]” and settles on wrestling for cash as a way to test his strength. He doesn’t first put on a mask because he wants to keep his powers a secret, but because he’s afraid of being embarrassed if he loses. His performance in the ring impresses an agent, the agent puts him on TV, and he’s a smashing success.

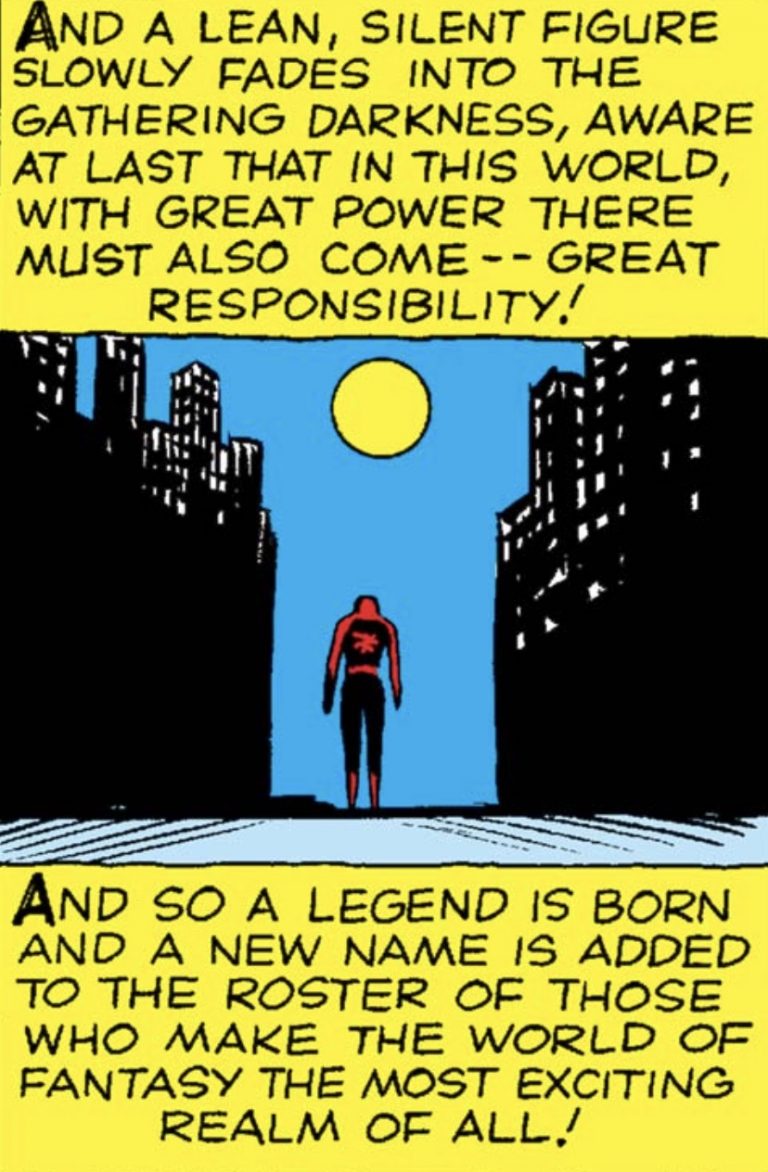

Next, Parker fails to stop the crook that shoots his uncle. Reading the story against later iterations highlights the extent to which Spider-Man is just a jerk at this point. In the Sam Raimi version, Parker lets the crook get away with the money after the wrestling promoter ripped off Parker. The promoter had it coming. In the first telling of Spider-Man’s origin, he just lets the crook get away because he does not feel like helping. In his own words to the cop, “Sorry Pal, that’s your job. I’m thru [sic] being pushed around — by anyone! From now on, I just look out for number one — that means — ME!” Like the other stories in the anthology series, this leads to an ironic twist: Ben gets killed, Spider-Man finds the killer, and he discovers it’s the guy he didn’t stop. Parker blames himself. The narration box chimes in at the end to provide the moral: “With great power there must also come great responsibility.”

A minor theme here is Parker’s own arrogance and toxic masculinity, though I doubt Lee and Ditko would have used exactly that phrase. It is developed somewhat over Ditko’s run, as most of the villains are evil mirror images of Spider-Man. His early villains (the Chameleon, Mysterio, the Vulture, Doctor Octopus, and the Tinkerer) are all aggrieved geniuses who decide to use their talents for personal gain and violence against innocents. Parker, having learned that great power must be paired with great responsibility, accepts his responsibility and fights the various evil geniuses, but there remains a bit of the arrogant Parker who took up wrestling just to test his strength. This is also developed more in some of the Spiderverse related spin-offs, including a version of Parker who really embraces his toxic masculinity after he gets his powers, and a version who turns himself into the Lizard and ultimately dies after his friend gets powers and he doesn’t because he desperately wanted to be special.

The tension between being an aggrieved nerd on the one hand, and embracing all the responsibility that comes with your power on the other, is what makes this such a compelling origin story. It’s an essential part of maturing, and not just through adolescence and young adulthood. You have the choice between looking out for number one or accepting the responsibility that comes with your lot in life. Parker’s recurring, internal conflict between those two options drives the character, much more than the external conflict of how he’s going to beat Doc Ock or the Kingpin.

In conclusion, here is a video of a cha cha (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QjcWXpvA5e8) and of a waltz (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBKTN6c_MEQ) . Now you know the difference, and you don’t have to be a professional wallflower.