Two-bit town though it is,

This is where I am king.

There’s a beat to the stride. A drag that isn’t quite a trudge, more like a steady walk uphill into the wind, closing your coat around you against the chill and getting pissed off to stay warm. Going to work, going home, going to the bar, maybe the bartender won’t shoot you in the head, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if he did. But you keep walking anyway to that beat and listen to the music that matches it. There’s a lot of that rhythm in Boston, just like there are a lot of cold and windy streets here. Thalia Zedek plays it, the Beatings play it. And Black Helicopter plays it.

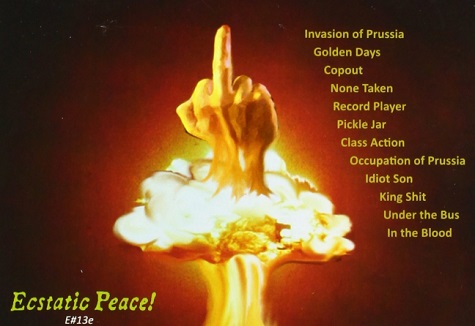

For a band that was ready to make a push for real success in 2010, Black Helicopter still wound up walking against the wind. A Boston Globe article from the time lays it out — the band’s third album was released on Thurston Moore’s indie label Ecstatic Peace!, which had a distribution deal with Universal. But Universal did not like the album’s title, “Don’t Fuck With The Apocalypse,” nor were they fond of the back cover art including a middle finger. And one of the songs had profanity in its title as well! Universal suggested changes, the band told Universal to pound sand, and the album didn’t get that big distribution push, although it did get some ink from the music press. It was their last full album to date.

The core of Black Helicopter, guitarist/vocalist Tim Shea and drummer Matt Nicholas, were working at a convenience store in the suburbs of Framingham in the early 2000s when they formed the band. An older guy would come into the store on a regular basis and subject them to whatever was on his mind that day, and after a while, Shea and Nicholas started recording him on the store boombox. With some tweaking, these rants turned into songs and the band’s first album. Some of this stuff is pretty crude (“Creme De La Bouche” is a truly vile story of sexual conquest), but then there’s something like “Mousemeat,” a circular narrative of despair that comes around to a chorus that’s simple and damning:

Go out

Go to the bar.

I’m drunk by nine,

Then I go to the store.

I buy the paper,

A Wall Street Journal.

Get a sandwich, cigarettes,

For the morning

When I wake up.

This is where the band found its groove, soundtracking tales of failure and day-to-day life with an ugly buzz of guitars over thick bass and remorseless drums. Shea’s plaintive drawl has drawn repeated comparison to Stephen Malkmus’ tone in Pavement, but Malkmus is “ironic and full of a smug wit,” as one reviewer noted, and there is no bullshit obfuscation in these songs. Shea isn’t always clear, but he’s never putting you on. The band can be as blunt as a middle finger rising out of a nuclear explosion, but the front’s Raymond Pettibon illustration of an angry Jesus brandishing a large snake is pretty explicit in tone if not quite scrutable in content. And the first track, “Invasion of Prussia,” eliminates all doubt of what to expect here. That beat kicks in immediately, heavy bass clomping away and soundtracking a doomed march into a dangerous land. “Don’t question the path,” Shea wails before heavily distorted guitars start squawking and blasting. “Don’t do the math.”

If there’s any happiness to be found here, it’s in the past, that place we’re constantly marching away from. “Golden Days” is a retreat to a place where someone “never left and said goodbye,” and while it has that plodding beat, it feels warmer. “Record Player” is a rare move to something overtly upbeat — a shuffle even! Shea sings about throwing on old records that you haven’t heard in forever and the joy that brings. “Play that song and turn it up … you haven’t felt this way for years.” It’s one of the shortest songs on the album, of course.

More typical is something like “Copout,” where a mournful lead guitar tracks Shea’s resigned lyrics. “Me, I’m doing fine,” he assures before he and fellow guitarist Eric Baird twine their sound into something that certainly suggests otherwise, but also says that of course that was how it would turn out. And then there are the stories. “Class Action” is a lengthy lurk in the mind of a guy getting evicted and how he’s sure that justice is on his side. “Idiot Son” is a rocker about, well, see title, a fucking schmuck whose family needs to figure out how to keep him employed:

And we’ll put in a call to Uncle Mike,

Get him a job out on the Pike,

Collecting tolls

And smoking bowls.

There’s gotta be something could be done.

The band excels at this kind of humor, which can be grim but also well-observed and rueful (although the Pike went full EZ Pass a few years back — where will the idiot sons go now?). What hurts this song in particular and the album overall is a lack of bite in the production. The band produced this album and frequently is wide of the mark on the full meat of their live sound. Everything is a bit too clean, and it rarely gets as harsh as the band should feel, the dynamic of raw sonics scraping against mundane frustration. That sense of the everyday is still strong, though, and it carries songs like “Pickle Jar,” the story of a guy who regularly rents one specific movie (what kind is pointedly left to the listener’s imagination), buys the biggest jar of pickles he can and then goes to town:

Now I’m back at my place,

I slap that flick right in.

Stop and rewind and slo-mo,

I like to watch it all blow-by-blow.

I got one hand on the clicker and the other’s in the jar

This has to be my favorite part by far.

“Pickle Jar” rules because its narrator is telling the listener what he does and how much he likes it, and any judgment is your own fucking problem. Anyone who’s watched a movie under less than savory circumstances can surely relate. The subject is comfortable with who he is, and Shea does not condescend to him in the slightest. It’s different on the album’s centerpiece, “King Shit,” the song whose title so scandalized those Universal twerps. The song’s first-person narrator is also in the music biz, he’s a promoter who thinks he runs the town. “I’ve been here since day one. Name the show, I’ve put it on,” Shea snarls over Nicholas’ backbeat and Zack Lazar’s thudding, menacing bass. Then the mournful guitar kicks in, and Shea and Baird drone over the empty space at the heart of this man, who promotes others’ work and talks a big game without having any core to speak of. The recognition of “Mousemeat” comes with the narrator realizing what he’s lost. Here, it’s the narrator understanding who he is. “Empty threats and posturing, I guess that’s my thing,” Shea confesses as the riff comes crashing down. “I’m on top of this town.”

Like “Mousemeat,” this is a song I can listen to endlessly, sinking into its remorseless undertow and self-loathing. I don’t have the regrets of these men, but who doesn’t have regrets? Who doesn’t feel protective of what they have because they know full well what they don’t? “King Shit” is a brutal song, but it is cathartic in its embrace of failure, and closing track “In the Blood” makes that embrace complete. There’s no menace here, just an understanding that it won’t get better. “The same mistakes, they happen all the time. Why they repeat I can’t identify,” Shea sings over guitars that almost sound cleansing. “I guess it’s in the blood. If I could overcome, I would.” You can’t beat what’s inside you. The song rides that weary beat for the final time, but ends in mid-step.

Black Helicopter has put out some EPs and singles in the years since Don’t Fuck With The Apocalypse and even recorded a live set for the local radio station last year. They’ve teased that they have material for a new album but have been quiet lately, even as the venues open up again. If they do put out a new record, I’ll be first in line, but I won’t expect it to break them wide. Reviews of Don’t Fuck With The Apocalypse were generally positive but not enthusiastic. Songs of weariness and acknowledgment of failure are not huge selling points. “Sometimes, though, the sense of futility achieves a kind of transcendence unavailable to younger, angrier punk rock,” a favorable reviewer notes. Another critic is less complimentary: “The songs did find their way into my head, but I’m not sure I was too happy about that,” they say, adding, “These guys are true rock and roll journeymen.”

I like that word, “journeymen.” It’s a status that can only be earned by time and work. A journeyman is a reliable person in his craft, according to old guild rules. To move beyond that, to become a master craftsman, you have to produce a masterpiece. I’d argue that people will be listening to “Mousemeat” and “King Shit” a century from now, but album-wise, Black Helicopter hasn’t produced a masterpiece yet. Then again, I don’t have any masterpieces to my name either. I have work that I do and try to do well, and when it’s done, I might check out a show.

For years, I’ve been able to hop on the subway or take a bus or even just walk down the street a ways and see Black Helicopter rock the everloving shit out of a cheapass venue in Allston or Somerville. Greil Marcus once looked back on 25 years of listening to Warren Zevon’s tales of destruction, self- and otherwise, and concluded, “From afar, he has been a good friend.” Black Helicopter have been good friends from close by during good days and bad ones, and I miss seeing them. Go out, go to the bar. I want to get out and hear this music live and loud again and walk home with my ears ringing and my head buzzing. And if not a spring in my step, a kick in my stride.