In the spirit of this movie, we present a hasty and unworthy follow-up to Sam’s essay on King Kong. Made on less than half the budget of the original and completed in only six months, Son of Kong* is an unwise cash-in on a scale that impresario Carl Denham could appreciate.

Denham (Robert Armstrong) is our main character now. Much of the Kong gang in front of and behind the scenes returned – or more accurately never left with barely time to pack a suitcase between the first film’s release and this film’s production – but not romantic leads Fay Wray or Bruce Cabot. Of the original two directors, Ernest Schoedsack returns but perhaps the most crucial retentions are scriptwriter Ruth Rose and effects supervisor Willis O’Brien.

The saga of O’Brien will wait since his contributions don’t show up until 75% of the movie is done, but Rose comes out of the gate swinging her strategy: make the movie funny when it can’t top the original in scale. Given the budget and delivery schedule, this accounts for that front 75%. I wouldn’t assume anybody who wasn’t an avid AMC watcher in the early 90s to be as familiar with this as its classic progenitor, so to recap:

We open on a shot of a poster advertising the disastrous Carnegie Hall appearance of King Kong, perhaps slyly reminding the audience that a grander movie just came out and possibly still plays at the theater down the street. It’s one month after the incidents of the first film, and Denham is being sued from all directions for the destruction caused by Kong (destruction of property, shock, anguish and a sprained ankle according to the latest summons). Later blockbusters would inspire many ex post facto tee-hees about the aftermath of monster destruction, and naturally Marvel would turn the idea into very serious business, but it’s worth noting that Song of Kong got there first.

Denham gets tipped off about a pending grand jury indictment, so he escapes to commiserate with the only two people who can sympathize, Charlie (Victor Wong) and Captain Englehorn (Frank Reicher) whose ship piloted Kong back from his home island in the first place. Englehorn is having legal troubles of his own and cuts Denham on his cunning plan: get the hell out of there before the authorities impound his boat. They jet away from their (alleged, pending a jury’s decision) responsibilities, leaving the superimposed names of half a dozen Asian port cities in their wake, until they reach one capable of rear-projection.

This film has a curious pace. It’s not quite 70 minutes long, and expository dialog gets spat out like that slim runtime was mandatory. And still every scene that denies us a Kong creates impatience. The first film also withholds its giant ape action for a surprisingly long time, and it’s impossible to claim anybody went into that movie without anticipating the main attraction, but somehow the wait feels longer this time. Maybe too much is put on the shoulders of Denham, who now pulls duty on the requisite romance plot in addition to getting the movie back to Skull Island. He meets the lovely Helene (Helen Mack, probably best remembered as the defenestrating girlfriend from His Girl Friday) as she performs a song at a sideshow in the port of Dekang. Her opening act is a band of tiny monkeys – Denham’s irritated boredom at the paltry primate show is another example of Rose’s wit – and her emcee is her drunken, racist father (Clarence Wilson). He’s soon killed by his drinking buddy, Nils Helstrom (John Marston) a stranded Dutch captain with a shaky accent to almost prove it, in a fight that also burns down the show tent.

Turns out the perpetually drunk and occasionally accented Helstrom is none other than the man who sold Denham the original map to Skull Island. Denham and the Skipper are broke and in their own words “bored,” and Helstrom soon has them convinced they left behind a hidden treasure on Kong’s island. They set out to sea with a skeleton crew and a stowed-away Helene.

Helstrom’s plan to get away from Dekang starts easily enough, but the second phase to radicalize the crew and incite a mutiny works a little too well. Within sight of their destination, the crew forces Denham, the Skipper, and Helene off the ship (Charlie leaves of his own accord) and then tosses Helstrom overboard after them when he declares himself the new captain. “Row, you blasted bourgeois!” snarls the newly collectivist crew from the deck. If their lack of hierarchy doesn’t make them all equals, the starvation following the loss of Charlie the cook certainly will.

Denham claims that the island’s inhabitants will “throw a party” when they see their lifeboat, conveniently forgetting that he unleashed Kong on their residence before he did the same for New York. The islanders have not forgotten, however, and the only thing thrown upon their arrival is a series of spears. The natives, of course, are an uncomfortable aspect of the original movie, but the positive thing is the studio brought back Steve Clemente and Noble Johnson to reprise their roles. Their ridiculous, stereotypical roles. You know what, forget I said anything, the positive thing is the natives are onscreen for an extremely short time.

Nothing stays on screen for long because we’re almost 45 minutes deep into this movie and it has a lot of ground to make up. Finally, the five remaining characters stumble across the promised SoK. “Well, if it isn’t a little Kong!” exclaims Denham as if they’ve bumped into an old high school teacher. “I didn’t know Kong had a son.” Never came up in their chats, apparently.

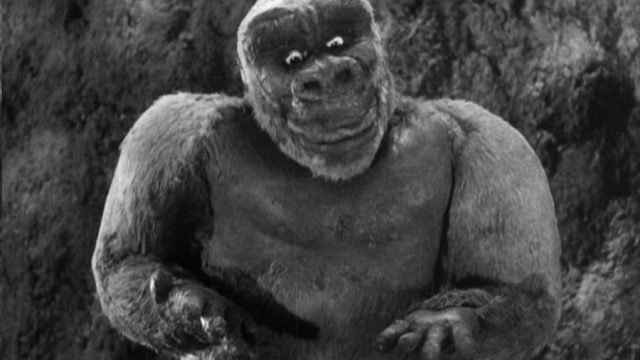

Kiko, a production nickname for the Son of Kong that I will use here**, differs from his father in several key ways. In addition to being an albino, he’s only twelve feet high as opposed to his father’s 18-24 feet (varying according to his proximity to a skyscraper). Temperamentally Kiko is as apt to provide comic relief as menace, gesturing and mugging in the style of a silent movie ham. He backs away, hand over face, when he witnesses Denham and Helene locked in a goodnight kiss and he comically knocks coconuts onto the pair when he notices them trying shake food from a tree.

Finally we’ve reached the monster mayhem we plunked down our nickel for. But again what can’t be made grand is made silly. The best parts of the fights fleetingly recall iconic moments of the first Kong, but they’re more often stop-motion WrestleMania. Kiko defeats the bear by putting him in a headlock and delivering blows. The bear taps out for a moment and when he returns Kiko beats him with a tree. During a fight with a giant bear he gets tossed against a cliffside and the film punches in for a close-up on his rolling eyes and even provides wacky clarinet accompaniment.

Kong was the monster with a gentle side, Kiko a gentle being who can pull monster duty as required. He’s more vulnerable. After the bear fight, the film’s best special effect shot composites the stop-motion Kiko with a practical hand. Denham wraps one of the giant, injured fingers in a bandage. “This is sort of an apology,” Denham remarks. Even “sort of” oversells it. It’s an apology befitting a guy who thought the village he nearly wiped out would celebrate his return: Sorry I got your Dad shot and tossed off the Empire State Building, here’s a bandage.

In a mere twenty minutes, Denham and Helene save Kiko from quicksand, Kiko reciprocates by saving them from the aforementioned giant bear, the other three in the party get trapped by a styracosaurus, Denham discovers there really is treasure on the island, Kiko fights a lizard monster, Helstrom is eaten by a what appears to be a hand puppet in a bathtub, and all remaining (non-native) persons make an escape in the lifeboat as a simultaneous hurricane-earthquake strikes the island until it sinks into the sea.

Denham, busy pocketing the treasure, nearly sinks as well, but he and Kiko climb to the highest point where Kiko lifts Denham above the rising waters until the lifeboat can come to his rescue. Kiko then disappears under the waves, bandaged hand lingering last.

It’d be giving way too much credit to say this is an Intolerance-like attempt to correct the racism baked into the original. Yet one can read something like a half-assed attempt in Rose’s acerbic script. The fact that Kong’s son is covered in white fuzz is likely just to differentiate the design from his famous father, but it also pushes against the idea that darkness is essential to the monster’s design. The film’s most verbal racist, Helene’s father, is killed by the drinking buddy he chose for being white. Mostly it’s interesting to see Denham, the guy who conquered Kong and dragged him away from home, grovel a bit before Kiko. On his way to getting a giant hand up when stealing the island’s treasure. You know what, forget I said all this, too. It’s too depressing to even entertain the idea that this might be somebody’s idea of setting things right.

Also depressing: the life and times of Willis O’Brien, the brilliant effects animator whose work inspired the original movie and gave its wonderful creatures life. To once again pick up the crumbs after Sam, O’Brien was less than enthusiastic about doing a sequel that he dubbed “cheesy.” Then his two young sons were murdered by his estranged wife during production and O’Brien’s already desultory participation dropped to somewhere around nil, with many of the effects handled by his assistants. Even so, he was clearly a strong tutor – while the animation is less grandiose than before, it’s still entertaining as hell, and the fact that Kiko can give a performance more along the lines of a Jar Jar Binks represents technical progress (if maybe a regression in other ways).

The real final word in this story is the reforming of Team Ape for 1949’s Mighty Joe Young – with Merian Cooper returning to produce, Schoedsack directing, Robert Armstrong on camera, and a more content O’Brien handling effects alongside his protégé Ray Harryhousen. But at the tail end of 1933, Son of Kong, like so many poorly conceived sequels after it, failed to impress audiences. A disappointing box office scuttled plans for another hasty film called The New Adventures of King Kong that would reportedly have taken place during Kong’s trip from Skull Island to New York, a strange “midquel” that may have anticipated the scrambled chronology of modern franchises the way Son of Kong apes resembles the supposedly modern urge to not leave well enough alone.

* The movie, technically The Son of Kong as appears on the screen, is nonetheless referred to as Son of Kong in most contemporary reviews and other places. It will be referenced as such here due to a lazy typist.

** Lazy typist.