When I was in college, one of the first ways I started discovering music I hadn’t heard before was by visiting AllMusic and looking for bands that influenced some of my favorites; finding connections between, say, Big Star and a host of power-pop type bands that came afterward, like the dB’s, Game Theory, or Mitch Easter’s Let’s Active. One day, a note I saw in the random trivia box piqued my attention: “R.E.M. has cited Television and The Soft Boys as major influences on their work.”

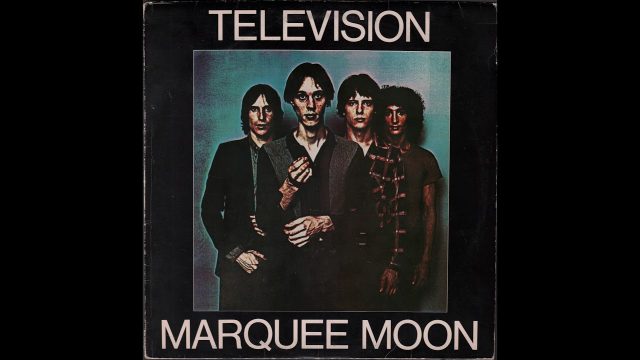

That was all I needed to hear, and figuring out where to start with Television was pretty easy: They only made two full-length albums in their initial run as a band. The second, Adventure, was generally considered “solid.” The first, however, was regarded as an all-time, epochal album: That, of course, is 1977’s Marquee Moon.

Television came up in the same New York City mid-70s punk scene as so many great acts of its day, but one particular element distinguished them from their peers: The guitar virtuosity of Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd. While many other punk bands stayed anchored in tighter essentially-pop song structures or more traditional blues-rock phrasing, Television abandoned that completely and allowed Verlaine and Lloyd to go on rhythmic and melodic runs and unique phrasing unlike any of their peers, just as often trading off showpiece solos as complementing one another. Rather than a typical lead/rhythm setup, the two guitars traded rhythm and lead parts and riffs as every song needed– and sometimes that meant both playing lead or rhythm parts. (This is not to discount the contributions of drummer Billy Ficca or bassist Fred Smith, who replaced Richard Hell in the lineup before Television began recording; Hell would achieve his own notoriety with Richard Hell and the Voidoids.)

In particular, it’s that interplay that made Television unique: Other bands in their scene simply didn’t have two guitarists this talented, and that allowed Television to create a back-and-forth with Verlaine and Lloyd’s play that often defied all sense but was compelling and indelible all the same. Sometimes the guitar intricacy is subtle, sometimes it’s in your face, but it’s always unique. (Apparently, Lloyd’s solos were precisely written and played, while Verlaine was more of an improviser.)

Verlaine’s songs are great, too; the eight tracks on Marquee Moon deliver lyrics both narrative (“Prove It”, for example) and impressionistic (“Marquee Moon”), perhaps no surprise given that Verlaine published a book of poetry with Patti Smith two years before the album. Verlaine told stories (largely formed in some way by his experiences in Manhattan) in a manner few other punk bands were attempting; with the band letting Verlaine and Lloyd’s guitar runs and expressions flourish at full length, these tracks were often quite a bit longer than your typical punk fare. The first three tracks are the shortest on the album, and the only ones under five minutes– closer “Torn Curtain” is nearly seven, and the centerpiece title track is over ten and a half minutes long.

The band managed to find a lot of variety in their signature sound in both the musicianship and the narratives. Opener “See No Evil” kicks off with a more standard, chugging riff before working in a more complex melody– and some nice call-and-responses and harmonies in the choruses, another technique the band uses well, including on the next track. “Venus,” lyrics about the heady intensity of love or drugs, combines its lower opening riff with a higher one that chimes in in response and also closes the verses, dancing around two different points on the guitar. “Friction” takes a groovy rhythm riff and lays an incredible melodic line and fills atop it, not to mention its frenetic solos. The great riffs of “Elevation” dropping out to let the drums carry the chorus. The picked-strum riff that opens “Prove It” would be echoed in X’s “Adult Books”; the song itself is a detective story of sorts, perhaps Verlaine’s take on New York noir, though the lyrics are so surreal and abstract it’s not clear what “that case that I, I’ve been working on so long” really is. Those rolling drums in “Torn Curtain” add to its stormy intensity. (Really, I haven’t mentioned Billy Ficca’s drumming enough, with his great fills and precise strikes.) The spareness of “Guiding Light” highlights Verlaine’s lyrics and makes for a moment of catharsis when the drums crash in and the instruments are released. All eight tracks are great, distinctive, and worthy in their own right.

“Marquee Moon” is one of the greatest tracks ever cut. The song alternates between verses of incredible interplay– the dueling riffs that drive this song are an all-time great pair– and long, inventive, frenetic solos, with equally wild and bombastic lyrics from the get-go: “I remember how the darkness doubled / I recall lightning struck itself,” for example. Verlaine describes the song as “ten minutes of urban paranoia”; remarkably, this comes across in only three verses (and a repeat of the first), mixed in with wild, unforgettable solos from both Verlaine and Lloyd, all anchored by the rhythm section to the origin point, where everything comes back before launching into the next verse. Tour de force has so rarely applied to a rock song as well as this.

Arguably, Marquee Moon is the most vital album in kicking off the post-punk era– taking the punk sensibility and expanding what could be done with it through inventive and talented musicianship and off-kilter, unexpected twists and turns through a song. (For an example: A couple of years later, Gang of Four’s Entertainment! would take inspiration and define post-punk in its own way, with tighter song structure but even more commitment to whiplash-angular guitar riffs, unexpected fills, and the like.) Their influence, especially in the dueling-guitar work, can be heard not only in other post-punk bands, but influenced everyone from indie-rock godfathers like Sonic Youth and the Pixies, to the guitarists of gigantic bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers and U2.

This isn’t even the first article I’ve written on the punk sensibility meeting guitar virtuosity; in Los Angeles, though, that meant showmanship, theatrics, and maximalism, laying everything bare and leaving nothing in reserve. In the New York punk scene, that meant an era-defining album, one just as full of inventive musicianship, but much more odd, mysterious, and sounding not quite like anything that came before: the marriage of punk sensibility, avant-garde poetry, and guitar mastery. Marquee Moon is one of the defining albums of the 1970s (even– okay, especially– consummate hipsters agree) and deserves a spot as one of the very best guitar albums in the entire rock-and-roll canon.