Like so many post-apocalyptic films, The Bed Sitting Room opens with bleak images of a destroyed world – molten rock, deserted beaches, the decaying face of a burning doll. But the next thing we see is a man wearing an outfit entirely made from mirrors, followed by a cast list, the actors listed in order of height. It is immediately clear that this is not going to be a standard tale of life after the bomb.

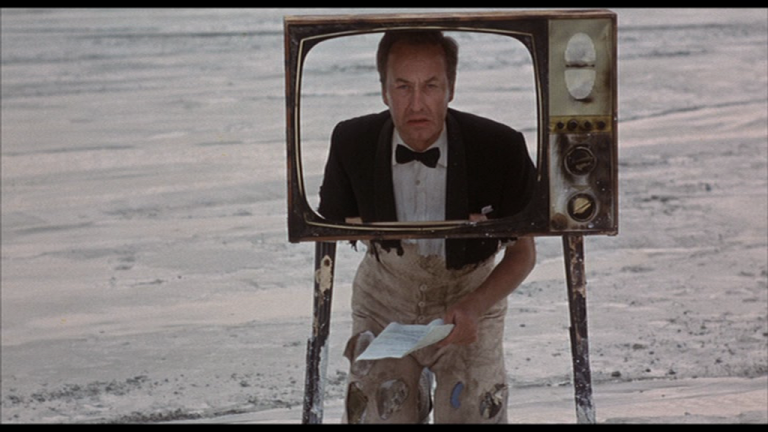

The opening scenes introduce us to the small group of survivors that still inhabit the radioactive remains of London. Three years (or possibly four – records are already spotty) after the exceedingly brief events of World War III – which we are told lasted just under two and a half minutes, including the signing of the peace treaty – there are roughly 20 people left alive, at least in London: Mrs. Ethel Shroake of Leytonstone, who has been deemed the closest in line to the throne and placed into power and the rest of mankind, who desperately cling to whatever deranged version of society they can. A former BBC employee hosts news broadcasts by crawling into a hollowed out television; a doctor attempts to offer advice to his hopeless patients; a family of commuters endlessly ride the last working Underground train, powered by one man on a bicycle.

The Bed Sitting Room is, at least by some broad definition, a comedy. It was adapted from a play written by John Antrobus and Goon Show legend Spike Milligan (a huge influence on both The Beatles and the Monty Python team), and the cast is stuffed with a who’s-who of late-60s British comedy talent. Dudley Moore and Peter Cook play the last remnants of the police force, shouting instructions from a rusted-out car that dangles beneath a hot air balloon; Harry Secombe emerges from a bomb shelter rambling incoherently about his ex-wife; and the wonderful Marty Feldman plays a sort of anarchic, barely helpful nurse. Milligan also appears, carefully carrying a cream pie across the devastated landscape in what inevitably, torturously turns into one of the most long-winded pie-in-face jokes in cinematic history. Richard Lester directs, and at times the madcap strangeness feels like an evolution (or perhaps a radioactive mutation) of his work with The Beatles on A Hard Day’s Night.

There’s a haunting, bleak sadness behind it, though, despite the surreal comedy. This is not a film to take the nuclear apocalypse lightly – every one of the survivors is badly shaken by the events of the war, and the constant threat of radiation poisoning is never forgotten… even if, in this case, the end result of succumbing to radiation is physical transformation, a surreal touch that gives the film its title. Veteran British actor Ralph Richardson plays Lord Fortnum, an aristocrat convinced – with good reason, it turns out – that he is turning into a building. After this transpires, many of the other characters end up using him as shelter from the radioactive fog. And it is around this point that describing the film starts to feel like talking about a particularly messed-up dream. The finale gradually turns up the bleakness, with a plot involving Rita Tushingham’s long-overdue baby giving Threads a run for its money, but the film has one last bizarre joke up its sleeve that turns a seemingly impossible situation into an extremely unlikely happy ending of sorts. Even if Dudley Moore does end up transforming into a dog.

Perhaps surprisingly, given its stage origins, a lot of what works in The Bed Sitting Room is visual. The bizarre settings do a wonderful job of conjuring up an unusual post-apocalyptic world – piles of abandoned shoes or broken crockery; a ramshackle carwash spurting dirty water over a wedding party; the makeshift Queen of England posing beneath an arch of broken-down kitchen appliances. Much of the time it’s hard to imagine how this would have worked as a play, but there are a few scenes in which characters embark upon weirdly touching, strange monologues where those origins suddenly make sense. As a film it’s so utterly baffling that it’s hard to say whether it truly works or not; it was barely released at the time due to a perceived lack of audience, and even with fifty years’ distance it feels more like a fascinating curiosity than a rediscovered gem. For fans of bracingly strange cinema and surreal humour though, it’s well worth seeking out; I remember my first viewing being a thrilling one, and while revisiting it made me more aware of its flaws it remains an incredibly interesting film.