Welcome to Pictures of a Revolution, a year-by-year study of the output of Revolution Studios. This year, theatre kids and Ice Cube join forces to kill Revolution once and for all.

The Prelude

2004 was basically a not-terrible year for Revolution, and that’s not a small accomplishment after the catastrophe of 2003. They had a less unwieldy slate, a few solid hits, and only one out-and-out flop, on a $35 million movie and not a $100+ million one. With one year behind them where people weren’t constantly writing op-eds about Joe Roth being an idiot, Revolution comes into 2005 with a little more confidence than they had before. They’re not just backing their usual dumb comedies (though there are some of those too), they’ve got some serious awards plays and another $100+ million action blockbuster in the mix. This confidence is of course met with yet more humiliating failure, failure that finally signals the imminent end of this company. Some of it actually isn’t their fault. A lot of it definitely is.

The Films

In 2003, Ice Cube became the first actor after the initial three of Willis/Sandler/Roberts to sign a multi-picture deal with Revolution. Three movies were announced to be made with Cube at Revolution. One was Willie, the inspirational true-story sports drama mentioned in the last article because Joe Roth abandoned it to answer the question “what if Christmas… was with the Kranks?”. Another was Clash, a beyond-generic-sounding action movie with Cube as an ex-con seeking revenge against the gang of criminals who killed his family and left him for dead. And the third was Are We There Yet? ($97.9 million, $32 million budget), the obligatory pairing of the tough movie star with rascally kids and the only one of the three to get the greenlight. In a New York Times profile on Cube while Are We There Yet? was filming, Roth and Cube talk about AWTY? as a calculation to branch out Cube’s celebrity beyond his niche of adult comedies and crime movies; Roth seemed to believe that it could do for Cube what The Waterboy or Punch-Drunk Love did for Sandler. I don’t know about that, it didn’t make him a superstar nor did it win him any respect for the change in genre, but it was a hit and did prove both men right about Cube’s ability to reach beyond his established audience.

I’ve gotten lucky during this series that these movies have been interesting to write about. They can be good, they can be bad, they can be the most boring shit you’ve ever seen, but whether by virtue of the context surrounding them or the films themselves, I haven’t yet been at a loss as to what to say about them. This streak ends with Are We There Yet?. This movie is not funny at all, but that’s not necessarily a problem, I’ve covered plenty of unfunny comedies here with little trouble. It’s that AWTY? is not funny in the most boring, predictable ways imaginable. It starts with sub-sub-Home Alone booby-trap slapstick and every subsequent joke is similarly second-hand kids-movie bullshit: groin injuries, people getting sprayed with pee and puke, animals attacking Ice Cube, a racist joke or two (Cube bribes a Chinese auto-repair technician with a Yao Ming trading card). All this (other than the racism) is executed with complete competency behind and in front of the camera, which doesn’t make any of it actually funny. It’s just adequately-directed and -acted presentations of jokes I’ve seen done the exact way hundreds of times before. When I’m laughing this little at a movie designed to be 95% hilarious hijinks, the short 95-minute runtime passes by quite slowly (this means that the 5% of “emotional” scenes actually come as a relief). It really makes you appreciate the hard work of something like Daddy Day Care, which is every bit as predictable as this but finds some fun angles within its cliches. This is just a filmed checklist of those cliches, and how much can I really say about that? I look forward to trying to find more to say about its sequel two articles from now.

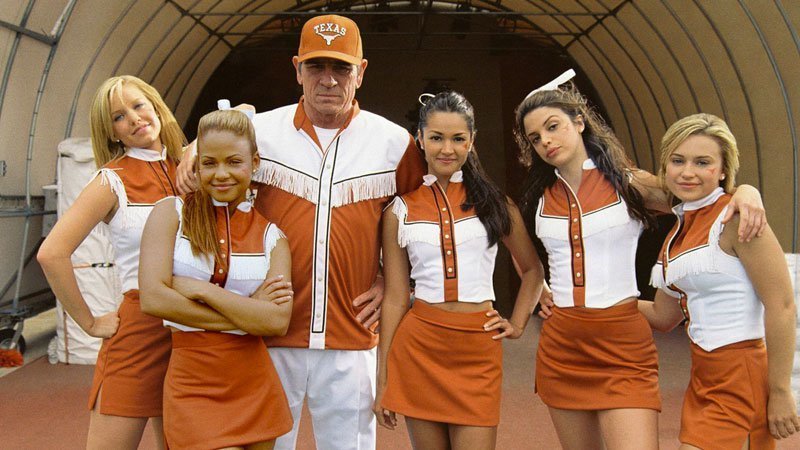

I don’t know if two years is enough to call an era, but if so, 2005 and 2006 were the era of Kelli Garner. It’s not that she stopped making movies after the mid 2000s but this was the time when she seemed like a star in the making, rather than just a working actor. It’s easy to see why she made an impression, she’s bubbly, conventionally attractive, and a strong comedic and dramatic actress. And Sony was more bullish on her than anyone, distributing (theatrically or on home video) four of the five released movies she made in this time period: Thumbsucker (which I’ve said my piece on), the solid Dreamland, the wretched London, and Man of the House ($21.6 million, $40-50 million budget), her one major-studio movie of this period. All of those movies either flopped or didn’t get the chance to flop, and after Lars and the Real Girl in 2007, most of her opportunities went to TV (including a Marilyn Monroe biopic for Lifetime and Pan Am). It’s a shame she stopped getting this kind of attention, because she’s good in all those movies and Man of the House points to an unfulfilled bright future as a studio comedy steady-hand.

When we last saw Tommy Lee Jones in this series, he was anchoring Ron Howard’s The Missing as a father very belatedly realizing the effect his leaving had on his family. It was a good part going deeper than just the gruffness that became his persona after The Fugitive, and he’s very good in it. Here, it’s all gruffness (he’s a Texas Ranger assigned to babysit five University of Texas cheerleaders when they witness a murder), and because he’s a pro, he’s still good in it. Blank Check posited that Tommy Lee Jones is so often good because even when he doesn’t seem to like the movie he’s inhabiting, he’s usually already playing a grump and his dissatisfaction just seems like good character work. This is the baseline of entertainment for Jones as the stone-face reacting to mischief, and Man of the House goes above and beyond that baseline. Jones seems to actually be having fun and making choices here, like him erotically describing a horrible-looking pizza that he’s ordered (he really draws out “extra-thick cruuuuuuust”) or how casually and unexpectedly he tosses off the easy joke of him saying his favorite movie is The Sound of Music. Jones isn’t the only one having a good time, his fellow grouch hall-of-famer R. Lee Ermey takes his 100th police chief part here and plays him more perpetually amused than angry, and a young(er) Shea Whigham is clearly enjoying himself in the perfunctory part of Jones’ eager underling Ranger. Even if you absolutely hate the rest of this movie, it might be worth watching just for the sight of Whigham in a “Keep Austin Weird” shirt.

In the history of indifferently-plotted action-comedies, Man of the House may have the most indifferent plot of them all. The movie can’t even pretend to care about whatever crime started this story, some rich guy named Courtland did something bad enough to need to bump off a government witness against him but fuck if I know what it was. There are periodic check-ins with Brian Van Holt as a hitman on the cheerleaders’ trail, but he’s an anodyne threat even by the standards of light comedies. Mercifully, the movie is very skimpy on these elements after the plot is set up and much of the rest is just TLJ learning from the cheerleaders how to be a better man to all the women in his life. It’s certainly not the most original plot, but originality isn’t a prerequisite for being fun and even a little sweet. I was previously taken by the female friendship angle of White Chicks and this handles that even better, there’s real camaraderie between the cheerleaders and an attention in both writing and performance to how their personalities bounce off each other. Garner is maybe the standout of the group, especially for how she avoids the traps of making her character (who’s failing her English class because she spends all her time practicing for cheerleading) a cliched airhead, but every girl in the group is well-performed and instantly endearing, you believe they have the power to melt Jones’ heart.

Back to Ice Cube. Revolution was in a pickle because Vin Diesel was refusing to return for the sequel to xXx. The studio commissioned two scripts, one by original xXx writer Rich Wilkes and the other by legendary studio hack Simon Kinberg, and Diesel disliked the Kinberg script enough to say no when that was chosen as the official script (director Rob Cohen meanwhile turned it down because he was busy destroying his career with Stealth). Revolution and producer Neal H. Moritz didn’t look particularly far for a replacement when they decided on making Cube the new lead, he had the Revolution deal and had just made Torque for Moritz. With Cube in place, Revolution went full-speed ahead on xXx: State of the Union ($71.1 million, $113 million budget) and bombed out in spectacular fashion. Anyone could’ve seen that a sequel to a megahit without the star who drove audiences to said megahit was asking for trouble, but these morons saw the writing on the wall and still decided to make State of the Union a full $25 million more expensive than xXx (even though an LA Times profile of Roth reveals that Cube’s salary was one-third of what Diesel would have made). Even after throwing obscene amounts of money at transparently bad ideas nearly killed them in 2003, they couldn’t help themselves, they lasted one year of relatively responsible financial decisions before kneecapping themselves again. This might have been the fatal blow to Revolution too, since its release came timed to negotiations between Revolution and Sony about possibly extending their distribution deal past its expiration in 2006. The deal was not extended, and Revolution partner Todd Garner (Roth’s second-in-command) resigned within a week of State of the Union‘s dismal $12.7 million opening weekend (on its way to an even more dismal $26.9 million domestic total).

While losing Cohen and Diesel was clearly a misguided financial decision, it’s not necessarily a bad creative one. Diesel, god love him, is pretty fucking bad in xXx, and even leaving aside that Cohen should be executed for the betterment of society, his direction of xXx is nothing any rando on the Sony lot couldn’t deliver. Of course, getting the once-promising Lee Tamahori, hot off the one-two punch of Along Came a Spider and Die Another Day, to direct instead has its own potential problems. Problems that come to light as soon as the movie opens, with an overcut, unexciting action sequence where masked soldiers siege the secret government agency (led by Samuel L. Jackson) that hired Diesel in the previous movie. For a high-octane action franchise, these first two xXx movies have action that doesn’t reach beyond bare competency, and this one has a new problem with an overload of janky CGI and digital speed manipulation. But there are improvements over the first to be had, some major. The biggest one is that Ice Cube is a much better lead than Diesel was. There’s little to Cube’s character Darius Stone except that he’s tough as nails, and luckily Cube excels at playing charming tough guys while Diesel strangled his own talents attempting to look cool and macho in the first one. And while I can’t say that xXx: State of the Union is a particularly progressive work (after all, Samuel L. Jackson reacts to a traitorous female character by repeatedly telling Cube to “kill the bitch”), there is some attention paid to the difficulties that would befall a Black secret agent wandering through the whitest areas of Washington D.C., which gives this a little more weight than the brainless boys fantasy of the first one (a scene where Cube embarrasses an NRA lobbyist by telling him to ask their membership to stop shooting Black people might even be a little gutsy for a Hollywood movie). And speaking of boys fantasies, with Cohen gone, there’s far less of the first movie’s puerile obsession with scantily-clad women. There’s even a running gag where Cube seems to be asking for sex but is actually asking for some good diner food.

Cube is a good enough lead that the James Bond-y spy elements of the movie, total afterthoughts in the first one, are a good deal of fun. But the fun doesn’t last ’til the end, when it all comes crashing down and Tamahori finally gives into his weakness for completely absurd digital chase scenes (remember, he’s the man who brought you this scene). The ending starts as Cube recruiting Xzibit and his team of professional carjackers to take on a military blockade (yes, they carjack a tank), a very fun idea reminiscent of the other, much better Diesel-less sequel 2 Fast 2 Furious. But it quickly gives up on that to eventually become a ludicrous chase between a bullet train, a sports car, and a helicopter, all three brought to life by very unconvincing CGI. It looks very bad, almost but not quite to the point of being charmingly bad. And it’s just not particularly satisfying to see Cube face off against Willem Dafoe, uncharacteristically sleepwalking through the movie as a Secretary of Defense with vague, possibly nonexistent motivations to kill the President. If you’re gonna demand the Speed 2: Cruise Control comparisons by making Dafoe the villain of your action sequel without the first movie’s main draw, at least let Dafoe have a little fun in the process.

Peter Pan was the only Revolution movie up to this point to have a distributor other than Sony, and even then Sony still coproduced and retained international distribution rights. But 2005 offers two Revolution movies with no involvement from Sony at all, both would-be awards players where Revolution came on-board as a coproducer. The first was Lasse Hallstrom’s An Unfinished Life ($18.6 million, $30 million budget), coproduced and distributed by Miramax and very nearly another Jennifer Lopez-starring headache for Revolution’s 2003. It was shot in early 2003 for a plum end-of-the-year awards release date, but Miramax pushed its release to 2004. Then it didn’t come out in 2004 either. According to the website Bomb Report, which unsurprisingly has pages on several Revolution productions, it and several other Miramax films were put on the back-burner to wait out the Weinsteins’ tense negotiations about their future at Disney. The Weinsteins even apparently offered Roth and Revolution the chance to distribute it themselves, but Roth declined. Please consider the weight of this rejection in light of the completely unpromising trash Roth was happy to distribute to 2000+ theaters. After it was announced the Weinsteins were leaving Miramax, An Unfinished Life was taken off the shelf and given an indifferent semi-wide release in 2005, alongside other Miramax titles that had been sitting in the reject pile (within a month, Miramax released this, Underclassman, The Brothers Grimm, The Great Raid, and Daltry Calhoun).

From 1999 to 2006, Lasse Hallstrom made six movies, all but one of them for Miramax (and that one, Casanova, was made for Miramax’s Disney neighbor Touchstone). This run made Hallstrom less of a director in his own right and more a personification of the idea of a “Miramax movie”: a well-cast, handsomely-shot, but terminally mushy drama always positioned as an awards player despite getting reviews no better than respectful. Whether or not these were the movies Hallstrom was passionate about making, they’re definitely the movies the Weinsteins loved to churn out, ones well-behaved enough to not hurt anybody’s feelings and ostensibly about serious enough issues to seem important (Miramax got Jesse fucking Jackson and the Anti-Defamation League to say that Chocolat was a powerful statement on intolerance and not the most forgettable piece of fluff ever made). An Unfinished Life is very much in this mold; it’s got beautiful Wyoming landscape photography, a trio of great actors doing solid work at the center, and messages about loss, redemption, and domestic violence, and it’s a complete snooze. It takes the path of least resistance at every turn, maintaining an almost insulting gentleness even through situations that would seem either too violent or too weird to merit such an approach; if it seems like Robert Redford is going to murder Jennifer Lopez’s abusive ex, he’s actually just going to point a gun at him and tell him to leave town. Mostly it’s just interminable scenes of people talking in short, slow bursts about the greatest tragedies of their lives: Redford’s son died in a car crash, Lopez was married to the son and behind the wheel during the crash, Morgan Freeman recently got mauled by a bear, even sassy restaurant hostess Camryn Manheim had a young daughter drown on her watch. They speak only in the mustiest old homilies about grief and forgiveness, so full of dramatic pauses it’s like the characters know that they’re saying the most profound, powerful things that will ever come out of their mouths (you can hear Freeman mentally polishing an Oscar with each monologue he gets about an obviously metaphorical dream he just had). There is no relief from this movie’s dramatic turgidness, not even when the ending involves a scheme by Redford to steal a bear.

Within John Carpenter’s miracle run from Assault on Precinct 13 to They Live, The Fog is a relatively lesser-heralded work. It’s well-liked among horror and Carpenter fans but doesn’t inspire the same level of passion as The Thing or Escape From New York, and Carpenter himself has expressed dissatisfaction with how it turned out. This is why the 2005 version of The Fog ($46.2 million, $18 million budget) is one of the few Carpenter remakes/sequels/whatevers to actually boast involvement from Carpenter, he and his early cowriter/producer Debra Hill produced it in an effort to get it right this time. But despite what they and others may say about it, the original Fog is a masterpiece, engrossing as both a shaggy study of a beach community and a nail-biting horror movie, and filled to the brim with gorgeous, eerie imagery. It’s a lot to live up to, especially since so much of its power is from Carpenter’s unparalleled mastery over the widescreen frame. But surely Rupert Wainwright, the man behind Blank Check (not the podcast, the “BUTT TO FACE” movie), will be up to the task.

One thing among many I like about the original The Fog is how it doesn’t even try to connect its various characters until they’re forced to band together against the evil fog ghosts at the end, they’re just living their own lives until something extraordinary pushes them together. Or it pushes them into their own corner, like how Adrienne Barbeau’s DJ Stevie Wayne spends most of the movie trapped in her lighthouse radio station on her own. An early sign that the remake wouldn’t be replicating this approach was a throwaway line, definitely not in the original, about how Nick Castle (played by Tom Welling here and Tom Atkins in the original) had been having an on-and-off affair with Stevie Wayne (Selma Blair). Then he picks up a female hitchhiker (Maggie Grace here, Jamie Lee Curtis in the original) like he does in the original, except this time she isn’t just a hitchhiker, she’s Nick’s ex-girlfriend returning to town and the daughter of the woman running Antonio Bay’s anniversary pageant (that I’ll maybe concede as a funny in-joke, since she’s played by Janet Leigh in the original). And she’s the one who delivers the exposition journal to Father Malone, instead of him finding it on his own and drinking away his sorrows alone until everybody hunkers in his church at the end. It neuters the original’s potent message about how all of us are liable to pay for the sins of those who came before us, becoming instead a movie about a few couples and families who these ghosts really fucking hate. Plus it makes Antonio Bay seem a lot smaller than it was in the original, a place where everybody needed for the plot are already familiar to save time. That lack of patience is all over this, abandoning Carpenter’s “the master shot’s enough” approach for boringly conventional cutting and favoring constant cheap music-sting shocks over Carpenter’s suffocating dread. Wainwright does craft some neat images from time to time, like a dinner-table set complete with candelabras washed up on the beach, but mostly he’s just working in less effective versions of what was actually scary the first time. His one opportunity to set this apart from the original is in the kills (the original is fairly bloodless and was even moreso before some bad test screenings), and they all look so fucking stupid that they just make me mad at this guy.

As the Tom Atkins-to-Tom Welling switch would make it seem, the bland new cast can’t hope to measure up to the personality of the original cast (everybody talking about how actors in the 70s had actual personality in their faces unlike the stars of now could be talking about these two movies; they even got some male-model-looking fuck to play Father Malone instead of Hal goddamn Holbrook). The one casting choice I had hope for going in was Selma Blair, even though she’s up against the best performance in the original. Barbeau in The Fog is one of the coolest characters in movie history, Stevie Wayne operates with the effortless chill of someone who knows they’re living their best life and seeing that chill broken by the end is as frightening as any of the bigger scares. I like Blair enough that I was optimistic she could summon up similar cool, but alas, she doesn’t deliver. Admittedly, she’s fighting an uphill battle to match Barbeau’s work if only because the remake’s focus on Maggie Grace means that Stevie gets a lot less screentime, but Blair is phoning in the time she does get, not doing much more than some serviceable radio-host snark. I was still rooting for her to overcome this junky movie until the scene where she witnesses (via Sony Vaio webcam of course) the death of Dan the weatherman, reduced to a screaming, flaming carcass getting tossed across the room (a pretty sick visual, I won’t lie). She reacts to this like someone just told her news of a C-list celebrity dying.

The second Sony-free Revolution production is Jane Anderson’s The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio ($689,028, $12 million budget), which also has the disheartening honor of being the first Revolution movie, after more than 30, to be directed by a woman (oh but don’t worry, there’s a whole one other of those coming soon). Based on the true story of housewife Evelyn Ryan sustaining her family on winnings from commercial jingle-writing contests, this was coproduced by DreamWorks via their production deal with Robert Zemeckis’s company ImageMovers. The book that was the primary source of my DreamWorks article, The Men Who Would Be King, says that DreamWorks executives hated Zemeckis and his refusal to actually produce anything for his deal, only stomaching working with him because he was Steven Spielberg’s buddy. Their antipathy for Zemeckis would go a long way to explaining why Prize Winner, another well-reviewed 50s Julianne Moore drama after the awards success of Far From Heaven and The Hours, was treated as something lower than scum by DreamWorks. It was shunted off to DreamWorks’ short-lived speciality wing Go Fish Pictures, which released it to 41 theaters in late September/early October and quickly gave up on it. I may give Roth plenty of shit, but at least he’s not this petty with his movies.

From what little I knew about it before watching it (mostly posters and DVD covers probably whipped by those same vengeful DreamWorks fucks), I figured Prize Winner would be a fluffy nostalgia piece, an ode to the bygone era of commercial jingles. It is that, and there’s a lot of charm in the cute montages of Moore explaining direct-to-camera how the contests worked or furiously working through a supermarket shopping-spree (Woody Harrelson as Mr. Ryan even makes sure to grease the wheels of the shopping cart before she starts). But the material is colored by a lot of scenes with Moore quietly struggling with the ramifications of being married to a violent alcoholic. Moore has to shoulder the burden of their extremely large family (ten kids in total) by winning contests because Harrelson keeps blowing his paycheck at the liquor store, and he is a frightening drunk. He’s filled with insecurities (particularly about a derailed singing career and Moore being the family’s “breadwinner”) that boil over with drink, he screams at his family and attacks whatever household item is nearest to him at the time. Some scenes play out in the feel-good manner you’d expect in the foreground (the Ryans celebrate the shopping spree by eating nothing but the most expensive food, Moore formulates a song about a sandwich), while in the background Harrelson stews in terrifying rage. The juxtaposition is especially brutal because Moore really does act like nothing is wrong in her household; it’s not that she’s holding it together for the kids, it’s that she seems to have actually gotten used to this behavior. It’s only when Harrelson craters the entire family rather than mostly just himself (he takes out a second mortgage on their house to get more drinking money) that Moore can’t look past his glaring problems.

Two articles ago, I covered Mona Lisa Smile, a perfectly pleasant movie with puddle-deep ideas of womanhood as it existed in the 1950s. Prize Winner is Mona Lisa Smile if it actually had anything meaningful to say on that subject. This is an unexpectedly wise movie with no easy answers about its protagonist and her life as a housewife. It isn’t a self-serious wallow in “gosh, being a woman sure is hard” like The Hours, there’s joy in addition to pain and sadness here and the movie understands that Evelyn Ryan fundamentally believed that she lived a good, meaningful life despite the hardship. It also understands that dramatizing that life makes it hard for the viewer to believe that too, especially when it boils down to Evelyn’s life only being in service of making sure her kids are more worldly and independent than she is. In the movie’s second half, Evelyn’s teenage daughter Tuffy comes to represent the viewer’s perspective (and also the burgeoning feminist movement that takes shape in the years after this movie is set) and tells her mother that Dad is an abusive lout and she has gifts that her standing as a housewife is keeping her from fulfilling. But Evelyn is genuinely happy with the life she’s been presented, even if brief tastes of other lives (a trip to Texas, a meeting with a group of fellow jingle-writing housewives led by Laura Dern) do seem tempting. This is a character and performance of the “you must imagine Sisyphus happy” school of thought, and Moore is remarkable at playing this kind of sad contentment without pitying or mockery, it’s easily the equal of any of her Oscar-nominated performances and definitely superior to at least a few of them. I don’t know if Prize Winner would have been too anti-inspirational for the Academy to support, but it really couldn’t have hurt DreamWorks to recognize that they had a powerhouse performance on their hands.

Sony kept one Revolution awards player for themselves, one that seemed like a surefire hit. Everybody in Hollywood wanted to bring the Broadway smash Rent ($31.6 million, $40 million budget) to the screen but the road there was long and full of people not willing to commit when the opportunity presented itself to them. Miramax got the rights soon after it premiered but had to wait until 2001 to do anything with them because the show’s producers didn’t want the movie to interfere with the original stage run. When 2001 came along, Miramax was set to make it with Spike Lee directing, a version that apparently got far enough along that Lee was considering casting Justin Timberlake in it. But Lee left due to budget disputes, and Harvey Weinstein attempted to throw together a cheap TV-movie version before Jonathan Larson’s family insisted on a theatrical release. When Chris Columbus expressed interest in directing it, Weinstein (like the generous, peaceful soul everyone agrees he was) let Columbus take his version to Warner Bros., a version that also fell apart due to budget disputes. Revolution was Columbus’s final destination, since he had a good relationship with Roth after he filmed Columbus’s Christmas with the Kranks script, and they greenlit it at twice Warner’s desired $20 million budget, plus $4 million to Weinstein to buy the rights. Everything ended up working out: Rent was another embarrassing bomb, likely because whatever zeitgeisty appeal Rent had greatly diminished in the nine years between its premiere and adaptation, it received zero (0) Oscar nominations, and Harvey Weinstein made out with $4 million that he probably spent on out-of-court settlements.

There are a few problems with the film of Rent that everybody brings up, the big one being that most of its cast is significantly too old to be playing their parts in it. Knowing this going in, I assumed this would just be true for the returning cast from the original Broadway run, a decade removed from when they could convincingly portray twentysomething bohemians. But then new addition Rosario Dawson, who had played a Will Smith love interest three years earlier, got a song identifying her as 19 or possibly even younger, like they decided to make everyone a problem instead of just fixing the problem with the original cast. Of course, now that Dear Evan Hansen takes the cake for most bizarre age-inappropriate casting, the difference between a 25-year-old and a 35-year-old doesn’t seem quite so egregious, and it’s far from the only thing wrong with this. The other oft-cited problem is the really insurmountable one, which is Chris Columbus. Rent aspires to be a gritty portrait of immediately pre-Giuliani New York, a setting that would be perfect for a filmmaker like, say, Spike Lee. Chris Columbus, meanwhile, works exclusively in broad family comedies and fantasies that don’t take place in anything resembling reality, which makes him a very peculiar choice for a tale of big-city drug addiction and the AIDS epidemic. It might still work if he gave up on realism entirely and just went for pure musical-theatre artificiality (again, this is something that Spike Lee could do extraordinarily well). But Columbus isn’t a strong enough stylist to do that, so instead he adopts a dull point-and-shoot approach to all the musical numbers that’s neither naturalism nor an interesting kind of Hollywood artifice. Any musical has to solve the problem of the inherent disconnect of people suddenly breaking into song, and Columbus’s flat canvas only makes the turns into song even more jarring than they might’ve been.

Ultimately, while Rent the movie has many flaws, they’re all academic next to the very glaring issue I do not like the music of Rent at all. Maybe I’m being unfair to Jonathan Larson’s great work because I didn’t listen to an original cast album or whatever as my first exposure to this music, but as presented here, these songs live down to the criticisms of this musical being obnoxiously squeaky-clean for a story about sad, depressing, and dirty things. Every song is either an overblown power ballad with limp electric accompaniment (Rob Cavallo produced the music for the movie and it sounds like it was produced by someone who made his living working with the Goo Goo Dolls) or exactly the kind of overly chipper, aggressively unaggressive number that makes people hate theatre kids in the first place. Occasionally a song will have some bit of clever writing, but every song is working in such a hammy, overwrought register that anything good gets buried underneath it (I want to enjoy the structure of “One Song Glory” but I’m too busy thinking about how much I hate listening to Adam Pascal’s bleating voice). It’s very sad that Larson never got to see his vision take off, but sometimes tragically young dead people’s visions suck just as bad as alive people’s visions.

The Conclusion

Those crazy kids in Rent raised a good question: How do you measure a year? Obviously, in terms of the financials, this is a cut-and-dry disaster of a year, but even in terms of film quality this is arguably a step down from the already painful 2003. Sure, Gigli is worse than all of these movies, but it’s the kind of grand miscalculation we’ll be telling our grandchildren about. The bottom three of this 2005 slate are the most contemptible kind of creative failures, they don’t even try and they still fail. And here’s Prize Winner in the middle of this write-off of a year, a beautiful movie never given a quarter of the chance afforded to the movie where a guy stops, drops, and rolls away from an evil ghost.

The Ranking (so far):

- Punch-Drunk Love

- The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio

- Peter Pan

- Black Hawk Down

- The Missing

- 13 Going on 30

- The One

- Hellboy

- Man of the House

- Stealing Harvard

- Anger Management

- Mona Lisa Smile

- Daddy Day Care

- The New Guy

- Christmas with the Kranks

- Maid in Manhattan

- The Animal

- xXx: State of the Union

- White Chicks

- Hollywood Homicide

- Rent

- Little Black Book

- America’s Sweethearts

- The Forgotten

- The Master of Disguise

- An Unfinished Life

- Are We There Yet?

- Darkness Falls

- Tears of the Sun

- xXx

- The Fog

- Radio

- Gigli

- Tomcats

Up Next: The prodigal Sandman returns to whip these fuckers into shape.