The final FAR of 2022 wants to acknowledge each and every one of you who contributed articles throughout the year, making this feature possible on a weekly basis. For anybody who sent regularly or even just one article: Thank You.

This Week, Days of Auld Lang Syne Teach Us About:

- expiring copyrights

- pro wrestling icons

- the end of stardom

- Iranian film

- digital filmmaking.

Take a cup of kindness yet for scb0212 and Drunk Napoleon for contributing this week. Send articles throughout the next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post articles from the past week below for discussion, and Have a Happy New Year!

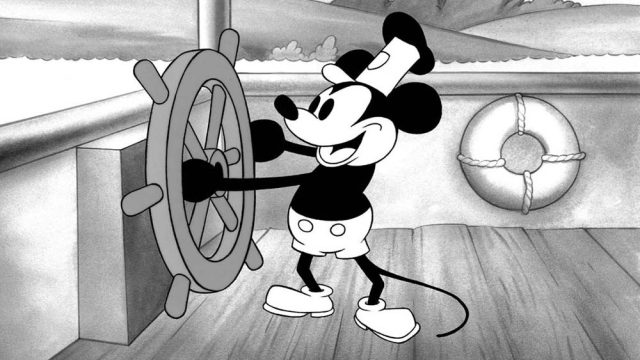

The copyright on the earliest version of Mickey Mouse will expire next year. The New York Times’ Brooks Barnes wonders what this could mean for the world’s most iconic mascot:

Winnie the Pooh, another Disney property, offers a window into what could happen. This year, the 1926 children’s book “Winnie-the-Pooh,” by A.A. Milne, came into the public domain. An upstart filmmaker has since made a low-budget, live-action slasher film called “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey,” in which the pudgy yellow bear turns feral. In one scene, Pooh and his friend Piglet use chloroform to incapacitate a bikini-clad woman in a hot tub and then drive a car over her head. Disney has no copyright recourse, as long as the filmmaker adheres to the 1926 material and does not use any elements that came later. (Pooh’s recognizable red shirt, for instance, was added in 1930.) Fathom Events will give “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey,” directed by Rhys Waterfield, a one-day theatrical release in the United States on Feb. 15.

For ReverseShot, Farihah Zaman reviews Jafar Panahi’s latest film No Bears:

Just more than halfway through the 20-year filmmaking and travel ban imposed on him by the Iranian government, Jafar Panahi has famously—and miraculously—spirited film after film out of the country. These are works that elliptically address living under a violent and oppressive regime without being reduced to or defined by them. Each is a message in a bottle to the outside world during a moment when the so-called Islamic Republic of Iran is attempting to isolate its people and hide the abuses toward them by restricting freedom of expression and the press, as well as controlling access to the internet. Panahi’s body of work in this era of confinement (including This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and Taxi) presents one of the most elegant and ingenious contemporary examples of art as an act of political resistance. His latest thoughtful docu-fiction hybrid, No Bears, is deceptively gentle, initially even comedic, lulling with a ruminative pastoral quality that is gradually pierced by painful reminders that these are more than stories—they are the contours of people’s lives.

In Filmmaker Magazine, Mark Asch recaps the march of consumer-grade digital images into pop culture ubiquity this past year:

This year also saw the continuation of one of the defining artworks of the digital century: Jackass Forever furthered the legacy of a show and film series which use digital cinematography to capture the antics of a group of friends looking gradually the worse for wear, and glimpses of its early, grainy camcorder days, like Alice Diop and Charlotte Wells’s home movies, take on the poignancy of a tattered family photo album. Jackass emerged in the rough-and-ready early days of prosumer DV, though its roots and inspirations go even further back, to a world of amateur skate videos traded virally in the years before YouTube—which, like all the major video platforms that emerged in the same decade that Hollywood shifted from film to digital, was seeded from its earliest user uploads with imitation-Jackass clips. As such, one of the near-death experiences captured in the Jackass cycle is that of cinema itself.

At The Ringer,

In the grand scheme of WCW’s success, Scott Hall’s Blockbuster card may be as important as Ted Turner’s Diners Club card. Al Pacino’s turn as the cocksure, ruthless, aggressive Tony Montana in Brian De Palma’s Scarface helped Hall craft his “Razor Ramon” WWE persona, which he’d parlay into his given name’s gangland enforcer character in WCW. Later, when helping form his new faction’s ultimate foil, Hall recommended Steve Borden check out Brandon Lee’s solemn, haunting portrayal as the titular character in The Crow. Sting’s always wanted to be something new, something people haven’t seen and something they wouldn’t expect. “Surfer” Sting—with his bright tights, usually emblazoned with a large scorpion, his Bart Simpson–esque bleached blonde haircut and cowl-shaped warpaint—was meant to separate him from the gruff and grizzled look of typical ’80s professional wrestlers.

Reaching back a few months – it’s the end of the year, the FAR is allowed to do this – to a piece from Nick Duerden at The Guardian that came from interviews with 50 pop stars about their lives after the spotlight moved on:

A great many never bothered to respond. Others enthusiastically agreed, only to later bail out. The guitarist from one of America’s most stylish modern rock acts, someone whose skinny jeans no longer fit quite as well as they used to, was initially keen, but cancelled at the last minute because, his manager informed me, “his head just isn’t in the right place to discuss this right now. It’s a difficult subject.” Those who did speak, however – 50 in total, from Joan Armatrading to S Club 7; Franz Ferdinand to Shirley Collins – were endlessly revealing and candid in a way they would never have been at the peak of their fame. I sensed they enjoyed the opportunity to talk again, to be heard above the din of Ed Sheeran and Adele and Stormzy. All were humble, replete with wisdom, resolute. (Many were divorced, too; at least one was high.) They’re the true Stoics, I realised. We could learn a lot from them.