Saturday morning cartoons were always a crapshoot. Late in the day, you could count on an X-Men episode but could also almost certainly count on it being aired in random order, part three of a four-part story in which the previous chapters ran five months ago. Middle of the morning involved skipping between channels, hunting for something watchable. And of course after noon was non-cartoon programming — a blasphemy.

Early in the morning seemed to be the most solid — an hour of Looney Tunes. Classics! Bugs, Daffy, the hope of a Road Runner. But occasionally there was something less familiar that apparently the CBS affiliate had the rights to, like that pathetic and loathsome rodent Sniffles the Mouse who somehow showed up every third week or so. There were surprises here, not always welcome ones.

Like this weird story of a guy who finds a frog. No dialogue outside of the frog singing nutty old music, which he only does when he and the guy are alone. The frog bankrupts the guy, drives him insane, and the guy finally throws the frog down a hole. And a century later, another guy finds the frog and the story starts again.

“One Froggy Evening” is widely considered to be one of the great cartoon shorts, a standout even in the oeuvre of the master Chuck Jones. I suppose the people of 1955 — specifically those people of Dec. 31, 1955, the original screening date — liked it, and Michigan J. Frog went from unnamed star to the face of the WB network as the century closed. But when I watched the short, several years before he danced across basic cable bumpers, he was as surprising and ultimately unwelcome as he was to the nameless schlub who discovers him.

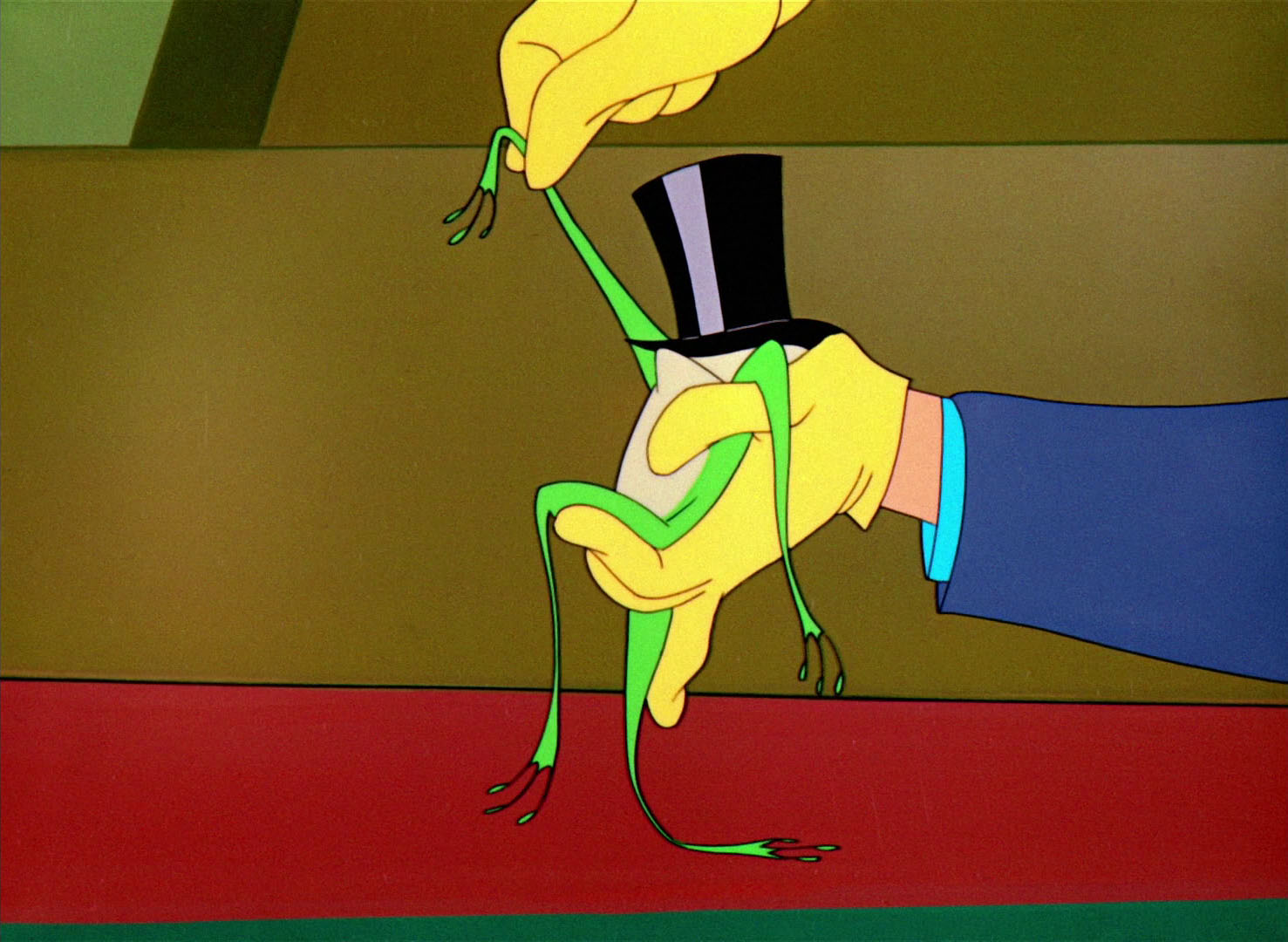

This is, of course, entirely on me. Today it’s obvious how much craft is present here. Michigan is a marvel, with the blaring cheerful voice of an uncredited Bill Roberts and the wide, expressive face that demands that you put on a show with him. His unnamed victim is a model of schlubbiness in comparison and the short’s genius is how it see-saws between their reactions, never in equilibrium or release — whenever Michigan is energetic, the man is aghast or amazed or beset, and when the man is enthusiastic and ready for entertainment, Michigan is inert.

His limp spaghetti movements while being forced to dance at the talent agency are a highlight, but his animation in repose is even better. He conveys not only stillness but the utter implausibility of making the movements we just saw, his bored posture denying all, revealing nothing. This is the foundation of this deranged Twain tale; the madness escalates as both the man and the viewer are unable to reconcile what we know with what the world is shown and believes — this drove the tightly-wound younger me nuts, but it makes for a merciless story.

And under the solid construction of a greedy man’s increasing folly is a weird background. Per Wikipedia, the story is a rip-off (as so manyLooney Tunes stories and jokes were) of prior pop culture, in this case the 1944 Cary Grant vehicle Once Upon A Time, about a theater promoter trying to turn a quick buck off a musical caterpillar. It’s hard to get box office numbers but it’s not in the top twenty movies of the year. And were people getting second chances for this to seep into the culture, the way movies did on video four decades later?

So the story is a decade old, maybe half-forgotten. The details of the story are outright impossible. Michigan is released from a cornerstone dedicated in 1892 — seven years before the song most associated with his performance, “Hello, Ma Baby!” was written and decades before other tunes he performs, like “I’m Just Wild About Harry.” What, are we to believe this is some sort of *snort* magic frog? Well, we better — in addition to surviving 63 years in the first cornerstone, Michigan lasts another century in his second prison before being released, just as full of music and mischief as ever.

.jpg)

This is ultimately what fascinates me about the cartoon — it’s a 1950s remake of a 1940s movie with songs from the Tin Pan Alley era of the beginning of the century, set in motion by events in the 1800s that predate all of these things while still referring to them. Listen: Michigan J. Frog has become unstuck in time.

And because of the looseness of copyright, he was still unstuck enough for me to discover him in the early 1990s, free from the context of greatness, in all of his frustration of tension and mockery of resolution. For a time, “One Froggy Evening” became itself, a twisted joke sprung on the unsuspecting.

Michigan’s status as Official Corporate Mascot a few years later likely stopped that for viewers a bit younger than me, and I feel like this was the unnamed man’s revenge at last — the ageless demon that tortured him with dreams of glory now forced, finally, to dance and sing on stage for an audience of millions. And as much as I sympathize with that guy, this seems like a punishment that’s worse than the crime.

But the WB is gone, the Looney Tunes evolving into the next attempt to grasp young eyeballs, and Jones’ glory is just another chapter in the history of animation. I hope that means Michigan J. Frog is back in his box, waiting, for a chance to come out again and surprise some new viewer with the same endless trick he’s had for ever, the only one he needs. He never sleeps, that frog. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.