When I was young, I loved magazines. At one point, I subscribed to 10 magazines simultaneously and went to two libraries on a regular basis to read others. I grew up in rural poverty and their glossy pages were like catching a glimpse into another universe. I read teen magazines, music magazines, and best of all: fashion magazines.

Fashion magazines have had “arts and culture” sections for as long as I can remember. These sections have things like TV and film reviews , short profiles actors and filmmakers, and coverage of film festivals and premieres. In my life, I’ve watched more movies thanks to these sections than anything else.

In an article that appeared in the fashion magazine ELLE in 1997, I first learned on the Cannes Film Festival. I had never heard of anything so glamorous. Sure, I’d heard of film festivals, it was the 1990s, so Sundance was a big deal, but seeing directors of independent films dressed in jeans and parkas during a Utah winter was no comparison to seeing European movie stars and models dressed to the nines on a beach in France in May.

The person covering the festival for ELLE raved about a film that had won three awards, but had been “robbed” of the festival’s top award, the Palme d’Or.

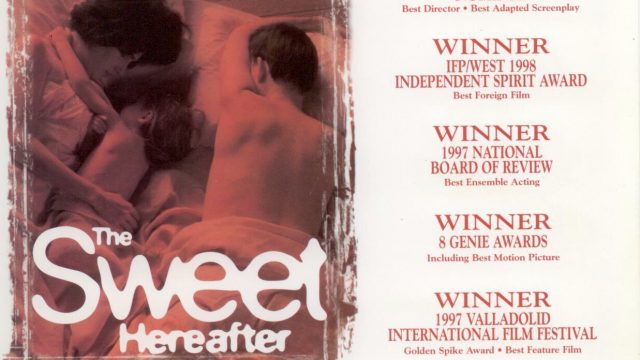

That film was The Sweet Hereafter.

I became obsessed with the film long before I ever saw it. I read the novel it was based on, I scoured other magazines to find more information about, and because my family didn’t have a computer at the time, when I was at the library, I did internet searches about the film and just about every member of its cast and crew.

Based on the novel of the same name by Russell Banks, and adapted by and directed by Atom Egoyan, the film The Sweet Hereafter uses a nonlinear structure to tell the story of a small town ripped apart after a school bus accident kills numerous children, particularly after townspeople get involved in a class-action lawsuit over the crash.

I’m not a fan of most nonlinear films, because it’s often a cheap way for filmmakers to try to give their works unearned depth, but Egoyan, who uses it in multiple films, never uses it as a stunt. One reviewer said that The Sweet Hereafter is about, “the beginning and ending of emotions, not about the beginning and ending of a story.”

Despite the suit being the ostensible center of the story, it’s really more of catalyst, as much as the crash, for telling the story. The lawsuit doesn’t matter because the parents in the film can never get their children back. There is no form of restitution or relief that will ever make their families hole again.

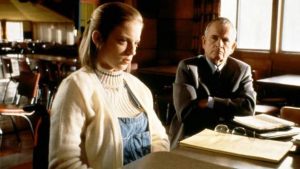

The film primarily focuses on four characters: bus driver Dolores (Gabrielle Rose), Billy (Bruce Greenwood), the father of two children that died in the accident, Nicole (Sarah Polley), a teenager that survived, but was paralyzed in the accident, and Mitchell Stevens (Ian Holm), a lawyer who comes to town and spearheads a class action lawsuit against the manufacturer of the vehicle.

As the movie goes on, we learn that there are many secrets and unresolved tensions among the townspeople that have been brewing for a long time, and that the lawsuit brings them to the surface. In many ways, it recalls Twin Peaks, another story about the far-reaching implications of a violent death on an isolated community. In one scene, Stevens interviews a couple, Wendall and Risa Walker (Maury Chaykin and Alberta Watson, two fine actors that are both sadly no longer with us), whose son died in the accident, and Wendall shares with him all the gossip he’s acquired about his friends and neighbors over the years. He sounds like he’s been waiting to say the stuff forever, but never got the chance until then.

Stevens has his own secrets under his calm facade, which seems to be why he becomes so enraptured with the case. Around the time of the crash, his own daughter, Zoe (Catherine Banks, Russell Banks’ daughter), a longtime drug addict informed him that she was diagnosed with HIV. He relates to these people who’ve lost their children, because his is essentially gone too. As he tells Billy Ansel, “Because we’ve all lost our children. They’re dead to us.”

In the film’s most stunning sequence, while travelling to visit his now-dying daughter two years after the bus crash, Stevens tells Zoe’s childhood friend Allison (Stephanie Morgenstern), whom he ran into on the plane, a story about how when she was two-years-old, Zoe was bitten by spiders and he had to hold a knife to her throat while his then-wife drove to the ER. While he’s excellent throughout the film, this scene propels his performance to one of the greatest in any film, ever:

Michell Stevens believes that he can save the town with his determination, just as he knew he could cut his daughter’s throat to save her life if he had to. He believes that if he does this, he might be able to save his daughter once again.

One of the great things about the film is its use of Robert Browings’s poem The Pied Piper of Hamlin, another tale of lost children failed by clueless and selfish adults, as a recurring motif throught.

Billy Ansel, who in addition to losing his children, also witnessed the accident as he was driving behind the bus at the time, sees how the lawsuit is ripping the town apart and tries to stop it, “We used to help each other, because this was a community,” he says.

But, it’s young Nicole who ultimately stops the suit. By lying in her testimony. Prior to the crash, Nicole was sexually abused on a regular basis by her father Sam (Tom McManus). Nicole, to punish her father, but also to heal the town, claims that Dolores was at fault. This kills the lawsuit.

When Stevens arrives at his destination two years after the main events, he sees Dolores driving another bus, and Nicole intones on a voiceover, “As you see her, two years later, I wonder if you realize something. I wonder if you understand that all of us – Dolores, me, the children who survived, the children who didn’t – that we’re all citizens of a different town now. A place with its own special rules and its own special laws. A town of people living in the sweet hereafter.”

In a way, we’re all in the sweet hereafter. Everyone last lost someone and can never go back to the time before, but the memories live on in the hereafter of the times that we shared with them.

Miscellaneous Stuff:

-The film that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes that year was Abbas Kiarostami’s A Taste of Cherry.

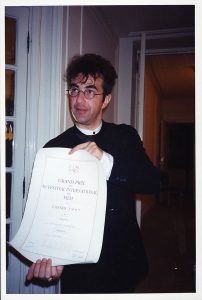

-Egoyan was the first ever Canadian to receive the Grand Prix at Cannes. Xavier Dolan became the second in 2016.

-Egoyan received Oscars nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay for the film. This makes him the first, and thus far only, Canadian director ever nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director a Canadian film. Other Canadians have been nominated (in fact, Egoyan was beaten by fellow Canuck James Cameron for Titanic), but they were all nominated for American productions.

-I didn’t see this movie until 1999, when I found a used copy of it for sale. As I said above, my family was poor and lived in the middle of nowhere, so we didn’t rent movies like everyone else or have cable. What I watched was confined to what was on network TV, what I found at the library, in bargain bins, thrift stores, and the previously viewed movies section at video stores when we ventured into town. This (combined with my severe ADHD) are the reasons why I haven’t seen as many movies as most people and will forever be The Embarrassment of The Solute ™.

-I never really read movie magazines (the closest I came was Entertainment Weekly), so I have no idea if there were obsessed with independent films in the 1990s-early 2000s as the fashion rags. Anyone know?

-I focus on the acting and story structure, but I want to give a shout out to the excellent score and cinematography, both of which are absolutely gorgeous. Everyone really brought their a game when making this movie.

-The actresses playing Nicole, Zoe and Allison look extremely similar. Egoyan admits this was a conscience choice on his part. When Entertainment Weekly put this film on their “Best of” list in 1997, they misidentified Stephanie Morgenstern as Sarah Polley.

-Shortly after this film was released in the US, Sarah Polley was profiled in the January 1998 issue of Seventeen magazine. As I had already heard of the film, this made me feel incredibly sophisticated and grown-up when I read it.

-I blame this film (and a weird show hosted by a pair of autistic bankruptcy lawyers that aired on local TV when I was young) for my incredibly stupid decision to attend law school. But, that’s another story for another therapist.

-Nicole and Billy are far less heroic characters in the novel, but I think the change works.

-The Pied Piper motif, one of my favorite things in the film, is also missing from the novel.

-The cover of the song “Courage” by the Canadian band The Tragically Hip that Polley sings in character in this has had an interesting afterlife, showing up in commercials and even an episode of the original Charmed.

-The original novel was inspired a 1989 bus crash in the small town for Alton, TX. In that accident, 21 students were killed when the school bus that they were riding in collided with a Dr. Pepper delivery truck, causing it to fall into a caliche pit of water. The Valley Coca-Cola Bottling Company paid out $133 million dollars in settlements due to the accident. Plus, the bus manufacture paid out around $1 million dollars for each child that was killed. 5 years later, the Los Angeles Times did a story on the aftermath of the settlements, and the discord it sowed.