Who Shot It: Gordon Willis. Willis, it is safe to say, did a lot to change the look of films, pushing the limits of screen darkness to their breaking point and inspiring countless imitations (in particular, Darius Khondji and Bradford Young practically owe their careers to Willis). Willis started out working with the likes of Alan Arkin (Little Murders), Irwin Kershner (Loving, Up the Sandbox), and Hal Ashby (The Landlord) before starting two collaborations that would go onto define his entire career. The first one was with Alan J. Pakula, with whom he shot the acclaimed trilogy of paranoid thrillers, Klute, The Parallax View (which features some remarkably disturbing widescreen images), and All the President’s Men, in addition to Comes a Horseman and the much-later Presumed Innocent and future series entry The Devil’s Own, the latter making for a tragically pathetic send-off to both men (Pakula died the year after it was made, and the production troubles turned Willis off of making any more movies). The second was with Francis Ford Coppola, whose work together consists solely of the three Godfather films, where Willis really took off as a pioneer of pure darkness in mainstream cinema. After meeting both men, Willis started a collaboration with James Bridges, which led to The Paper Chase, Bright Lights, Big City, September 30, 1955, and Perfect, in addition to bouncing from director to director, making films with James Toback (The Pick-up Artist), Robert Benton (Bad Company), Herbert Ross (Pennies From Heaven), and Harold Becker (Malice), and even directing one himself (the misbegotten former entry Windows). But what I really want to talk about today is his work with Woody Allen. The two started working together with Annie Hall, where Willis’s visual invention helped to bring Allen to a higher level of filmmaking, which only grew as the two continued to work together. They worked together to craft the chilly, bleak imagery of Interiors, the jaw-dropping black-and-white imagery of Manhattan, Stardust Memories, and Broadway Danny Rose, and the ingenious faux-degraded footage of Zelig. Their final film together was The Purple Rose of Cairo, perhaps the culmination of Willis “training” Allen as a filmmaker, and where Willis and Allen create possibly the most realistic fake old movie-within-a-movie ever and contrast its monochrome vibrancy with the main character’s dull, washed-out daily existence. And they also made A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy together.

What Do You Mean, Story?: Every year, Woody Allen releases a new film. Sometimes, when we pray to the sun god, we get two new films in a year (although in 1987, we caught the sun god in a bad mood and he only gave us September as a bonus film to Radio Days), or, in the case of this year, two projects. This year, Allen has seen fit to give us Cafe Society, a period piece in 30s/40s Hollywood and New York that didn’t quite get the “return-to-form” notices I expected it to based on its trailer, but still sounds like everything I want in an Allen film (a loaded cast, jokey looks at gangsters and Hollywood phonies, third-person narration, in this case from Allen himself) as well as the too-good-to-be-true prospect of him working with Vittorio Storaro, in addition to an Amazon TV series which features a multitude of great comedians, character actors, and actresses known for playing pop stars with secret identities. So, in honor of this momentous occasion, I have decided to feature a Woody Allen film on this series, for the first time since a monthlong series nearly two years ago. Hopefully this will wash out the taste of fucking Hot Tub Time Machine 2.

I’ve talked about how Woody Allen’s run from 1983-1987 is my favorite run of any director ever, using Allen’s abilities for both comedy and drama to extents that they probably weren’t used before or after (my two favorite Allen films, and two of my favorite films of all time, come from this period). But like all great periods in between a director’s beginning and end, they’re inevitably bookended by lesser works. The second bookend for this period is September, my pick for Allen’s worst, an airless chamber drama enlivened by the typically good technical aspects and a terrific Elaine Stritch performance. The first bookend is the film I’m covering today. In actuality, A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy was made entirely after the beginning film of this period, Zelig, but that film took so long to finish due to its complex special effects that Allen’s bosses at Orion Studios insisted that he whip up something quick. He did, writing Sex Comedy‘s script in two weeks and getting it into theaters a year before Zelig. While the film was better-received than Allen’s previous film, Stardust Memories, its reputation has diminished to the point that at least a few Woody Allen fans might be completely unaware of its existence. But I’ve defended plenty of other forgotten/maligned Allen films in the past. Is this one of them?

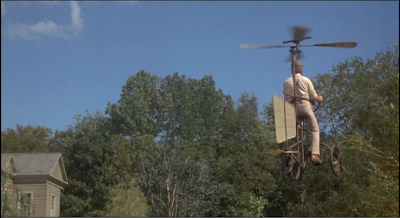

The film centers around three couples in one house in the country, sometime during the early 1900s. Andrew (Allen) and Adrian (Mary Steenburgen) are married, but their sex life has stalled, leaving Andrew to work tirelessly on his various crackpot inventions (in case you’re wondering, yes, Allen does get to look like those schmucks in the stock footage of failed flying machine tests). Philosopher Leopold (Jose Ferrer), Adrian’s cousin, and Ariel (Mia Farrow, in her first of 13 films for Allen), Andrew’s lost love, are about to be married, and have come to Andrew and Adrian’s house to do so. And bawdy doctor Maxwell (Tony Roberts), Andrew’s friend, and his nurse Dulcy (Julie Hagerty) are mostly just along for the ride. As befitting a film with “sex comedy” as part of the title, couples begin to split apart and fall for others. And befitting the Shakespeare reference as part of the title, spirits enter the picture, possibly guiding the couples to find love.

Like I said, this script was written in two weeks. I don’t know if even just another week would have ironed out some or all of the kinks, but this feels like it could’ve used at least one more tightening session. The script is a mixture of outright goofy comedy (like a botched lovemaking session between Andrew and Adrian in the kitchen where he tells her not to fuck him where they eat oatmeal) and drier conversations where the comedy is theoretical, if it’s there at all. This leads to a bit of ping-ponging between tones, making it harder than necessary to completely give oneself over to the film’s charms. Not helping with that is the ending, which is abrupt enough that it feels more like the final reel got chopped off than a natural end point. In this regard, the film looks ahead to Allen’s more clumsily-scripted later work from the vantage point of Allen near his artistic prime, fitting for a film where a spirit ball unleashes visions.

Look, I’ve said before that I love Mia Farrow as an actress (that qualifier is important). I think that the complaints about her as an actress are post-split BS. In fact, she’s given at least two of my all-time favorite performances, in The Purple Rose of Cairo and Broadway Danny Rose. So I’m sorry to report that I think that she’s one of this movie’s biggest problems (I’m even sorrier to note that I now agree with the Razzies, who nominated her performance here for Worst Actress). To be fair, more than a touch of this is on Allen. He wrote her role for Diane Keaton and gave it to Farrow when Keaton was too busy. Farrow has said that Allen was too hands-off with her during shooting, and Allen has agreed. Her performance on film certainly looks like one from someone who’s a bit adrift. Really, she’s wrong for the character, who’s portrayed as such an erotic being that she can draw any man to her, which Farrow doesn’t really pull off. And she looks like she knows she’s wrong for the part, because she looks pretty uncomfortable, sporting a pained smile through much of it, which helps to kill the laugh lines or scenarios that she’s given (you can really imagine Diane Keaton throwing herself into those jokes with aplomb, which makes matters worse). The rest of the cast is more than able, especially Roberts, Hagerty, and Ferrer, but none of the characters are really as central to the film as Ariel, which means that the film ends up centered around a black hole.

If those last two paragraphs make it sound like I’m completely down on the film, I should establish that, overall, I liked it. Yes, I’m a very easy sell on Woody Allen (there are maybe four movies of his where “I liked/loved/adored it” would be going too far to describe my opinion of it), but despite the many hiccups along the way, I found myself more often than not being engaged in a comfort food sort of way with the film and its charms, however slightly obscured they are. In particular, I was pretty delighted by a sequence where everybody sneaks out on their partner, many not getting what they came for, and two of them, separate of each other, come back and concoct the same story about falling asleep in the bathtub. It’s a featherweight trifle with not a lot to say and not a lot for the viewer to chew on, and I say that with all due respect.

Screw That, Let’s Talk Pretty Pictures: I am fully aware of both Woody Allen and Gordon Willis’s visual prowess when I say that this movie has some of the most gorgeous color photography of both men’s careers. From the first shot, where Jose Ferrer walks out of the darkness, on, this movie is a visual delight. The first half of the film takes place entirely in beautiful sunlight, shining on the house and its surrounding nature in a way that just celebrates life (there are some shots here worthy of Days of Heaven). Allen’s preferred wide shots are used here (there’s one early on that harkens back to the shot of everyone ready to play tennis in Annie Hall, and one that wonderfully frames Allen and Steenburgen in the corners of a mirror as they venture away from the camera), but here they reveal the extent of the beautiful grass and trees surrounding and overwhelming these small little people with ultimately small problems. A concentrated dose of Willisian darkness really doesn’t show up until the second half, which takes place at night, a perfect time for violence to strike and shadows to begin to appear (the arrival of these blacks coincide with one character attempting suicide and missing). But by the end, the characters have learned to live with the darkness, Andrew and Adrian even indulging in a lovemaking session so surrounded by negative space that it calls back to that gorgeous shot of Isaac and Tracy on the coach in Manhattan.

Favorite Shot/Sequence: This one was a no-brainer. There’s a particularly gorgeous sequence early on that shows a montage of nature sans humans of any kind that’s the anti-urban equivalent of the opening sequence of Manhattan.

Is It Worth Watching:

Stray Observations:

- This is the first movie to feature the Woody Allen credits that we all know and love; Windsor Light Condensed credits with old music (in this case Felix Mendelssohn’s “The Wedding March”) playing over them, with the cast members assembled in alphabetical order.

- Guys, I cannot wait for Cafe Society.

- Well, I made it this whole piece without directly mentioning wait, nevermind. Man, that was close, we almost had a disaster on our hands.

Up Next: Please make sure to bring your Pepto-Bismol with you for the next entry.