Mr. Narrator!

This is Bob Dylan to me

My story could be his songs…

— The Minutemen, “History Lesson Part 2”

The end of We Jam Econo: The Story Of The Minutemen is the Minutemen jamming econo. D. Boon has traded his Telecaster for an acoustic guitar, Mike Watt has another acoustic guitar instead of his trusty thud staff (that’s Pedro-speak for bass) and George Hurley is tapping out the rhythm on bongos instead of his drum kit, all of them sitting together on a small stage. They’re playing “History Lesson Part 2,” one of their quietest songs to begin with and here it feels almost like a folk tune — though the video footage is from the mid-80s the sound could be from the early 60s. But instead of narrating an old story or a current injustice, Boon is singing about he and his band, how they came to be and what they do. What they could be. “Our band could be your life,” is the song’s famous opening line, and embedded in that is another truth and hope: Your band could be your life. But what happens when your band is gone? Where is your life now?

The end of Inside Llewyn Davis is the same as its beginning: The title character is quietly strumming his own acoustic guitar on stage at New York City’s Gaslight Cafe in early 1961, isolated in a cold column of light dissolving into the cigarette smoke of the audience, shown up close by a camera that shudders with intimacy. He’s performing the 19th Century ballad “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” by himself and while Davis plays a pretty good accompaniment the real draw is his voice, a low and weary tenor that can carry the song’s story of a man who wants to set down a burden. As an opening scene it’s a show of what this man can do, and of course he is punched in the face and knocked cold shortly afterwards. The tricky structure from writer/directors Joel and Ethan Coen then flashes back to the week leading up to this moment for the bulk of the film without indicating it’s a flashback. When the performance reprises at the movie’s end, it has a different resonance — maybe its tale of longing and resignation is not literally true but it’s where Llewyn is. Your song could be your life. But was it really your song? “If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song,” Llewyn tells the crowd. They laugh appreciatively.

***

Inside Llewyn Davis is a sad film, sometimes painfully so, and one of the things that makes it so sad is how Llewyn misses and more often rejects connections — being a dick to people he cares for and fucking over people he’s fine with using — and how so many of these people in his orbit seem to be similarly lonely. But even as they’re all looking out for themselves, these satellites are part of their own universe, what is eventually called a scene. There are places like the Gaslight where people can play and places like a fellow musician’s apartment where they can stay — Llewyn spends the entire movie couch-hopping, sometimes crashing with his sister but more often with fellow singers, including a guy he just met. There are more intimate connections and ways for people in the scene to hurt each other, and Llewyn is an ugly participant here — he’s impregnated fellow singer Jean, who’s dating his buddy (and yet another fellow singer) Jim, and needs to pay for her to get an abortion. There are agents and money men, people sniffing profits and taking their rake, and more insidiously keeping the gates (literally, like the Gate of Horn club) from art that risks falling below the bottom line — but there are also fans and friends, like Mitch and Lillian Gorfein. They’re an older couple of academics who also put Llewyn up for the night and put food on his plate, and while their relationship can uncomfortably shade into a cross between condescension and totemization it is also forgiving and earnestly based in love for him and his music. We never find out how the Gorfeins met Llewyn or how they got into his music in general (although they seem to have an ethnographic interest in folk cultures), and if anything they might be an embarrassment — one of Llewyn’s comrades is fairly dismissive of them — but they are part of this scene too.

It is very clear how the Minutemen formed. A young Boon fell out of a tree onto Watt when they were in middle school in the 1970s and they became fast friends growing up in San Pedro (pronounced pee-dro), a working class neighborhood of LA with a strong shipping presence due to the port and old naval base. Boon’s mother encouraged him to play guitar and Watt played with him, although neither very well — in one of the funnier interviews in We Jam Econo, Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea laughingly recalls how the fledgling band assumed tightness and looseness of guitar strings was a purely aesthetic choice, not a way to perform the essential task of tuning the instrument. They listened to plenty of rock, but later in the decade discovered punk and that was it, they hooked up with drummer George Hurley and became a punk band named The Reactionaries. And when Boon and Watt went to a Clash show in 1979, they ran into Black Flag bassist Chuck Dukowski handing out fliers for a show in Pedro. Naturally, he asked them to play the show and the Reactionaries had their first gig. After the departure of the lead singer and a few shufflings not uncommon to dudes in bands in their early 20s, they’d reconfigured into the trio of the Minutemen and their first EP “Paranoid Time” came out in 1980 on SST, the label founded by Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn. It was the label’s second release.

Ginn, a notorious crank and weirdo along with being a virtuoso of ugly guitar and a person who helped create the independent music landscape, is not present in We Jam Econo. But a lot of compatriots from those days are and are happy to reminisce. The largely filmed-on-video interview subjects include journalists, roadies, SST producer Spot (whose treble-heavy sound defined the label); Black Flag and Circle Jerks vocalist Keith Morris, admiring contemporaries like Minor Threat/Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye. And tons of other musicians whose bands followed Black Flag’s lead and played house parties, VFWs, anywhere with a PA and that was willing, at least once, to accommodate a crowd of slam-dancing fans ready to tear shit up almost as a requirement of their fandom.

Hardcore, the meaner and faster style of punk that Black Flag arguably created, quickly became defined and trapped by its tribalism (although some people like Flipper defiantly proceeded at their own plodding pace). The Minutemen played as fast as anyone, their first LP The Punch Line has 18 songs and a runtime of 15 minutes, but they were not interested in continually toeing the line. Boon’s wiry guitar leads and chicken-scratch chords, Watt’s furious melodic basslines, Hurley’s manic drumming (former Black Flag vocalist Dez Cadena points out how Hurley leads from the top of the kit, not the bass drum) created a different sound that when (slightly) slowed down and stretched out became even more distinct, with Boon’s hoarse shouts of he and Watt’s often-abstract and abstruse lyrics adding another dimension. “I’m in a political straight jacket / my mind’s bent well defined ambiguity / I’m already on someone’s list as a casualty” is fairly easy to parse from that first LP’s “Straight Jacket,” a few years later Watt was writing things like “One Reporter’s Opinion,” he and Boon and Hurley using their twisting music to tie terse metaphors and koans together, laying out mini maps to where they were at:

What could be romantic to Mike Watt?

He’s only a skeleton, his body is a series of points

No height length, or width

In his joints he feels life

His strongest connection

Between the yelling and the sleep

Pain is the toughest riddle

He’s chalk, he’s a dartboard, his sex is a disease, he’s a stop sign

Punk has many possibilities, along with many definitions and many people eager to define it. I’m willing to define punk as whatever Mike Watt says it is and what Watt says in the film, from the vantage point of 2003, is both definition and possibility: that punk is doing your own thing. The paradox of his scene is how it is a place for people outside the norm trying to do their own things and that creates norms of its own, along with a framework for pushing back on those norms and anything else that’s pushing on you.

All that pushing can be antagonistic in a good way, or at least a fun one; at one point Llewyn bashes through “Green, Green Rocky Road” with the clear purpose of annoying people he’s trapped in a car with and it’s almost joyful spite, finding release in a song that lets you let that out of yourself. But later in the film he behaves far worse, heckling a woman at the Gaslight who is attempting to make her first public performance, and she breaks down in tears instead of performing “The Storms Are On The Ocean.” Which is an old Carter Family song that the woman actually heard growing up in Arkansas — she is the one true folk artist in the movie in the sense that she is continuing a lived tradition rather than glomming onto old music with a pedigree, and Llewyn savages her before saying he hates folk music altogether. His petty purism goes from dickish to completely wrong, but he’s also reeling from the just-obtained knowledge that his forthcoming Gaslight gig — the one we see at the start of the movie — is due to Jean sleeping with the club’s sleazebag owner on his behalf. His scene is full of phonies, his merits are meaningless and everyone is fucking each other. No wonder he wants out.

And the Minutemen’s scene has its own issues, as some wild footage of a 1981 gig shows. Watt yells at the crowd that has literally spat down his throat before he resumes playing, a little further away from the front of the stage as before. (Hurley, in an interview decades later: “Being spit on kinda sucks but you can’t see where it’s coming from so you can’t blame anybody.”) And as he’s driving around in the present, Watt passes the site of that first Reactionaries gig, then a Teen Post and now a different building, and has harsh words not for the changes now but what the audience did to the place then. The crowd came down from Hollywood to his hometown and trashed a community hangout, Watt recalls. “Funny how hardcore was supposed to be revolutionary but it works against people supposed to support, maybe that’s why it went racist? They come down here to this poor neighborhood, wreck these people’s Teen Post they just fixed up.” No scene is immune to ideals becoming dogma or people looking for excuses to be dicks.

***

The Minutemen’s scene eventually consumed itself in a circle pit of its own making, with plenty of politicking and shady business decisions along the way, but at least it gave its participants the chance to climb over each other literally as well as figuratively. Llewyn is on the bottom rung with no way up. He needs gigs at clubs, he can’t play a rec hall, and there’s no mad genius in a band named after an insecticide willing to put out his music — he can’t even get his agent to send his records out. Llewyn is trying to make his music his life but there is very little chance of that being successful when the hierarchy of major labels and promoters is involved, there’s only so much room at the top of the pyramid. So Llewyn looks for opportunities wherever he can — he takes a session musician gig to record the dopey novelty song “Please Mr. Kennedy” (especially because the payout will help him pay for that abortion for Jean, the sick irony is that Jim gets him the job in the first place) and he takes a road trip to Chicago with a horrible jazzman and his unnervingly Starkweather-esque poet accomplice just to make a pitch to one of those gatekeeping promoters. The ride is almost a parody of how the Minutemen and Black Flag and countless other punk bands would roll in subsequent decades, a bunch of musicians getting pissy with each other while crammed in a car on an endless drive to the next stop on the tour (former Black Flag singer Henry Rollins titled his memoir Get In The Van). Those trips might end with a show at an empty hall, Lleywn winds up facing something more damning.

Because he’s been on a last chance power drive. He has no prospects in New York but in a frozen and desolate Windy City, Bud Grossman is running the renowned club The Gate of Horn and his venue and label are able to make a folk singer into a pop artist, someone who can reach the masses and maybe get a damn roof over his head. Llewyn’s agent said he had sent Llewyn’s album (titled “Inside Llewyn Davis,” of course) to Grossman; when Llewyn cadges a meeting with the man, Grossman clearly has no idea who he is. But he is willing to give Llewyn a shot, and this reflects the Coens’ particular wry cynicism regarding the nobility of artists — they refuse to stand with them on principle and frequently give the money men integrity of their own. Earlier, the studio guy cutting checks for “Please Mr. Kennedy” tells Llewyn — twice! — how taking cash now will bone him on royalties later, there is no chicanery and even some caution here but Llewyn takes the short gain. He has his reasons, but he can’t say he wasn’t warned. And here, Grossman sits down and asks to hear something from “inside Llewyn Davis,” and Llewyn thinks for a minute and plays “The Death Of Queen Jane,” a ballad from the goddamned 16th Century about one of Henry VIII’s wives dying in childbirth. Childbirth and women being very much on Llewyn’s mind — while paying for Jean’s abortion, he’s learned another woman he knocked up secretly kept the child instead of getting the abortion Llewyn thought she did — and he plays the absolute hell out of the song, stopping his guitar to sing the final verse unaccompanied, staring directly at Grossman. In We Jam Econo, punk drummer Vince Meghrouni talks about punk as played by the Minutemen as something more than a set of signifiers: “It was immediacy, intensity, honesty, expression … exploring the things that interested [them] and exploring it hard.” This is what Llewyn is doing, but also with the instinct and confidence of a showman who has the juice to do this on a larger stage. Look at me, that final verse says. Look at what I can do. Look at what I have done.

What follows this performance is probably the most famous line in the film, as Grossman gives his judgment: “I don’t see a lot of money here.” It’s worth lingering on this for a minute. F. Murray Abraham’s delivery is dispassionate and timed with throat-slitting precision — it does not step on Llewyn’s performance, but comes after the least possible time needed to reach a decision like this. And the wording itself is just as precise, there is no hyperbolic condemnation and maybe even an acknowledgment of ability, the implication that there is a non-zero amount of money here. But not a lot. And a lot is what Grossman is looking for, and we know that despite the power of Llewyn’s performance that he’s right, a song like this won’t make a lot of money. Despite how a 400-year-old song can speak to and through an artist, it doesn’t have that commercial appeal, does it? Who even knows who Queen Jane is? The slyest and cruelest joke in the movie is how that novelty song Llewyn played on is just as ephemeral — a joke about an astronaut worried about what will happen back on earth should the president send him to outer space; a different president will be in charge when the moon landing defines the space program a decade later — but it is implied to be a hit, or at least on its way to becoming one. The Coens make sure to show Bud Grossman’s New York counterpart in the recording booth as Llewyn and his fellow musicians perform the song and his face shows the expression of a guy seeing a lot of money here. Queen Jane was the third wife of Henry VIII, a guy whose second wife Anne Boleyn is the only one to crack the popular memory these days. But she’s the subject of a folk song that has lasted to Llewyn Davis, and while the comical plea of a hapless would-be Alan Shepard could be a folk song in 400 years, it can definitely make money now. So who’s to say the reverse couldn’t happen, and that Queen Jane could have her moment in 1961?

Grossman is. He acknowledges Llewyn’s talent at least, and tries to recruit him for a trio he’s putting together, one that will play folk songs that regular people can really enjoy. Llewyn would have to clean up a bit, though, lose the facial hair. That’s a signifier, one of the things the Minutemen denied in spirit — their look rejected the uniform of punk’s safety pins and mohawks and leathers in favor of flannels and surfer hair and the world’s ugliest wingtips, which was its own purposeful indication of a blue-collar and “regular” life — but Llewyn can see what’s behind it. Grossman’s trio won’t be honest or intense, it won’t explore anything, let alone explore it hard. Llewyn can play his song well, can play it in a way only he can, and no one gives a shit. He doesn’t even have his scene to fall back on, partly because of his own selfish actions but also because everyone in the scene is chasing greater success over supporting each other’s truest expressions. Llewyn is all alone and he politely declines Grossman’s offer to join a phony group, but Grossman isn’t through with his advice. And the hell of it is, his advice is not bad. He tells Llewyn he’d work better with a partner, which Llewyn acknowledges he once had. Get back together, Grossman says. Good advice, Llewyn responds.

***

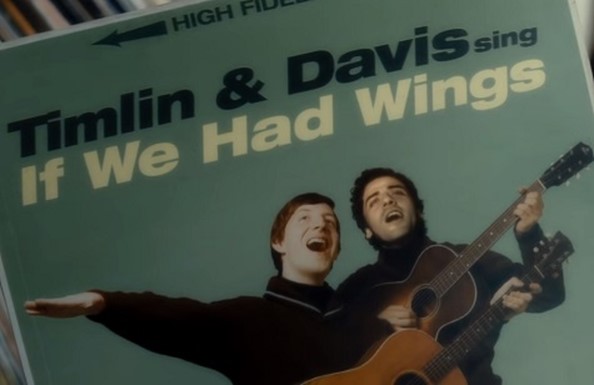

That partner, Mike Timlin, has been dead for some time. As writers, the Coens a far too good to fall into the trap of the unstated trauma, where everyone in a movie talks around something bad until the Big Reveal near the end. The full explanation that Mike suicided by jumping off the George Washington Bridge comes midway through the movie (and is revealed in the movie’s first trailer!), with Llewyn stating it outright, and before then it’s clear that Llewyn lost the partner shown early on via the cover to the Timlin & Davis LP “If We Had Wings,” and that that loss was permanent and painful. Llewyn and his friends don’t talk about it directly not because of a writerly affectation but because they can’t. This becomes agonizingly clear when the Gorfeins prod Llewyn into performing at a party and Lillian Gorfein begins to sing Mike’s part on “Fare The Well (Dink’s Song)” instead of leaving it silent. In a preview of his rant against the Arkansas singer Llewyn tears into her, and while he is horribly cruel it is plain how much this loss is still devastating him, and how an attempt to fill that void, however well-meaning, feels like an insult. Lillian and Llewyn share their musical scene but that’s not the same as sharing a band. Not just anyone can be a part of that. Your band could be your life.

We Jam Econo was released in 2005, 20 years after D. Boon died in a freak van accident. Director Tim Irwin and producer Keith Schieron structure the film chronologically, laying out the band’s history as it happened and not bringing up Boon’s death until the end, but even if the viewer has no prior knowledge of that his absence in present-day interviews is immediately apparent, much like the missing Timlin haunts Inside Llewyn Davis. And in particular Boon’s death is still devastating to Watt. In one of the movie’s first scenes Watt walks through a park and points out the tree Boon fell out of, landing on him and immediately launching into George Carlin bits. The tree is still there and Boon is not, just his memory. “I was quite smitten with him,” Watt recalls in his charmingly gruff voice that is clearly holding back tears.

Early in Inside Llewyn Davis we see Llewyn pull out “If We Had Wings” and put it on the stereo, and we hear Mike’s voice (provided by Marcus Mumford) joining Davis’ own on “Fare Thee Well,” the only time he’s actually present in the movie. But We Jam Econo is full of Boon’s music — guitarist Joe Baiza attempts to emulate his live-wire “brittle and bright” treble on the guitar, chuckling at his half-realized approximation — and his presence via concert footage. “I never saw a fat guy move that much,” Dinosaur Jr. guitarist J. Mascis recalls before footage shows Boon hopping and bopping while tearing through the immortal riff of “Corona,” known to anyone who’s ever watched Jackass. Watt generally stays in place while he plays, intensity radiating off him, and Hurley is a cyclone but still stuck behind the drum kit; Boon pogos across the stage like a madman, cracking the boards in his insanely ugly shoes, before sending a surprisingly clear tenor (when it isn’t barking or shouting) through the mic. And he gets to speak in old interviews, in particular a lengthy one that was filmed in 1985 at Bard College. In the footage Hurley is wearing a T-shirt with a Sharpied dollar sign design and Watt looks like he’s understudying for the role of Young Fidel Castro in fatigue shirt and heavy beard but Boon is just a husky guy in a polo, sometimes enthusiastic and sometimes bored or a bit annoyed with how things are going.

And at that point, things had gone surprisingly good! After continuing to tour and churn out EPs and short albums, the band had recorded another full-length in late 1983 when they got word fellow punks and friendly rivals Hüsker Dü had just recorded a double album. The Minutemen promptly recorded another two dozen songs to make their own two-LP set, “Double Nickels On The Dime”, which came out in 1984 and not only got good-to-great critical notices but sold pretty well to boot. It’s subsequently been recognized as one of the landmark albums of the 80s and has the band branching out into quieter material like “History Lesson, Part II” and “God Bows To Math” while still keeping more aggressive sounds like “Political Song For Michael Jackson To Sing.” In some ways it’s a departure, the band is more in sync with each other than ever but embraces a bit more space in songs — not that much, you don’t fit 46 tunes on a double album by writing epics — and its punk-funk turns almost jazzy at times, simmering rhythms underneath darts of poetry that are more audible than before. The songs are political and personal, full of frustrations and anger and also blues goofs like “Jesus and Tequila” and some of the funniest song titles known to man (“The Roar Of The Masses Could Be Farts”) along with lyrics that poke fun at the world and their place in it. “We were fucking corndogs / We’d go drink and pogo,” Watt writes and Boon sings in “History Lesson, Part II,” lovingly clowning on themselves in a way anyone who’s had fun at a show can understand. But this isn’t ironic distancing, it’s part of seeing where they are and planting a flag for anyone who cares to find it. “They made their own world in a rock band, that’s even more rare than being a good band,” rock journalist Joe Carducci says.

The Minutemen followed “Double Nickels” and their increase in stature — R.E.M., the biggest and most respected independent band in the game at that point, asked them to open on some 1985 tour dates — by recording the EP “Project: Mersh”, with “mersh” being Pedro-speak for merchandising. It was partially an ironic embrace of more commercial sounds and recording techniques — “’Project: Mersh’ is no more a career move than our first record, it’s just a different way for us to tell our story, we’re trying to get rid of the chains people had of our description,” a grumpy Watt says in the Bard footage, not realizing how much he sounds like a typical pop musician plugging the direction of his latest album — and partly what happens when two members of the same band have different ideas about what to do with their music. Longtime roadie and grade-school friend Richard Bonney calls Boon and Watt “twins with a secret language” but acknowledges that that language didn’t stop them from arguing. The Bard video has some amusing moments of them talking over each other, wrestling over the narrative of where they’re headed, but that is minor compared to blow-ups friends describe. A buddy who lent the band his garage to rehearse in recalls a neighbor calling to complain about the volume — not of the music, but of Boon and Watt yelling at each other. The two “broke up” the band at least once, during a massive argument in the van, and then had to wake up Hurley to try to persuade him which musician to stay with. Watt’s mom knew the score though. “They’d fight over ideas,” she says in an interview, “but you don’t fight with a stranger the way you fight with someone you love.”

***

Did Llewyn and Mike fight? It’s not clear. Maybe Llewyn’s anger with the world and his weariness with himself for not fitting in it came after Mike’s death. Or maybe his pissier qualities were there before but could be bounced off and mitigated by a friend he loved. The cover of Timlin & Davis’ LP “If We Had Wings” shows the two of them next to each other with Timlin’s arm and Llewyn’s guitar spread out, the both of them together suggesting the shape of a bird. It is cheesy as hell and this much is clear: They were fucking corndogs. And now there’s just Llewyn, no one to argue with or play with or even play for. He’s only a skeleton, his body is a series of points, his sex is a disease, he’s a stop sign. He somehow has a more dispiriting performance after his rejection from Bud Grossman, when he visits his merchant mariner father at a convalescent home and plays him “The Shoals Of Herring,” a seafaring song for a man whose faculties are mostly gone and who can no longer see the sea. It is gorgeous and full of love, and Llewyn’s father shits himself at the end of it.

It’s the final straw for Llewyn, who has a merchant mariner’s card himself and decides fuck folk singing, he’s going back to sea. But his union dues are overdue and another decision he made earlier in the film screws him over, marooning him on land and keeping him in a scene he is increasingly sick of. And just as the Coens play fair with the suits’ reactions to Llewyn’s music, they play fair with Llewyn’s reactions to the music around him. “The Last Thing On My Mind” is performed earlier in the film by the sweet-voiced Army man Troy Nelson, he’s the same guy that Grossman is building the next big group around, and Llewyn clearly can’t stand his earnestness and polish. One of the factors that sets Llewyn toward heckling that poor Alabama woman is the performance right before hers, a pseudo-Kingston Trio take on “The Auld Triangle” that is technically superb while sanding the edges off a song about rotting in prison. It is a pleasure to listen to, but should a song like that be a pleasure? (The late and truly great Shane MacGowan offers a superior version.) And these performances were anticipated at the start of Llewyn’s week from hell in one of the funniest scenes in the movie, when Nelson brings up Jean and Jim to perform “500 Miles” as an obvious riff on Peter, Paul and Mary’s ringing harmonic folk. It really is a lovely song and Llewyn thinks it is total bullshit. He doesn’t say as much, in part because the Gaslight audience is eating it up and singing along, but the look on his face is clear: Are you fucking kidding me? (I know this look and this desire not to go beyond it for fear of a furious crowd, I had the same expression on my face the one time I was dragged to a Dashboard Confessional show.) The audience loves it, but the roar of the masses could be farts. Llewyn is an asshole and in some ways just as big a poseur as anyone here, it’s not like he heard these songs working the fields or the railroad. But he’s trying to find something in them beyond a melody, something that speaks to what he can’t say.

And Llewyn finds it. The movie loops around to the beginning and we see how we got there — Llewyn lost the Gorfeins’ cat and went on a journey and failed to find success but hey, the cat came back and Llewyn too is welcomed back by the Gorfeins, who forgive his outburst and embrace him and his truly regretful apology. The cat almost gets away again but Llewyn catches it, the world turns but not quite to the same place it left. The gig at the Gaslight is a corrupted gift but as the Minutemen might tell him, you play where you can. And after we revisit that performance of “Hang Me,” Llewyn then plays “Fare The Well,” solo, and in doing so says goodbye to his partner. Like MacGowan after him, Isaac hits his consonants hard instead of the standard technique of emphasizing vowels, and the “LLs” he gets out of “well” are digging inside Llewyn Davis and pulling out grief and longing. “Sure as the bird flyin’ high above / Life ain’t worth living without the one you love,” is how Timlin and Davis conclude their version of the tune, Llewyn changes things up: “If I had wings like Noah’s dove / I’d fly up the river to the one I love.” It’s an acknowledgement of the gap that can’t be crossed and a goodbye to the person on the other side. Llewyn doesn’t have wings but he does have this song. And then he has a faceful of fist, courtesy of the husband of that Alabama woman, righteously pissed at the asshole who ruined her performance the other night and maybe her life. They’re going back to Alabama, no stardom for her, and while Llewyn slumps over in the alley behind the Gaslight,the next act takes the stage. His voice sounds familiar.

***

“I used to hear him a lot … his words are like your pop talking to you,” Watt says of Bob Dylan in We Jam Econo. He’s looking back on the opening track of their LP What Makes A Man Start Fires?, “Bob Dylan Wrote Propaganda Songs.” It sounds like a confrontational song but 1. it’s the truth and 2. it was Watt’s way of getting over his insecurity about writing topical songs. Bob Dylan did it! “I’m waiting and diverging, I’m collecting / Dispersing information, liberation,” Watt’s song says. But before Bobby Zimmerman was Bob Dylan, propagandist and icon and gnomic chronicler of his life in a way that inspired some dudes from Pedro, he was a folkie.

And he is here at the Gaslight in the final moments of Inside Llewyn Davis, singing “Farewell.” “The coming of Bob Dylan would indicate that [Llewyn’s] music would from that point on be the music of the past, rather than a living body. It wasn’t obsolete, but folk music was now a part of history, rather than just being in conversation with it,” Michael Guarnieri writes in his scholarly, insightful and essential breakdowns of Inside Llewyn Davis’ soundtrack at this site, which I have used as a resource over and over again while working on this essay. Dylan doesn’t know Llewyn Davis — this isn’t Walk Hard — but he’s about to cast him aside anyway. “It’s not the leavin’ that’s a-grievin’ me / But my darlin’ who’s bound to stay behind” Dylan sings, and he’s never been one to deny his path forward, wherever it leads him and whoever falls by the wayside. Nothing is guaranteed in this world, not a folk song and certainly not the success of a person who sings it.

But if that’s the case, there can still be a place for the certainty of a person — of people together — and a song for a brief space of time. Maybe for just a minute, man. Boon and Watt may have fought a lot about their songs but in that Bard interview they were unified on how they should be heard and who should hear them:

“Working people should be able to go to gigs, start the gig at 7:30 … our experience was with arena rock being so much [about being a] spectator, we came up on this new scene, it wasn’t about being spectators, it was about being a participant.” — Watt

“There should be more interaction with music and everyday people … We play how we want to. We want people to know, there should be a band on every block, there should be a nightclub on every other block and a record label on every block after that.” — Boon

Llewyn Davis goes on an odyssey halfway across the country in a futile attempt to land a gig and find a record label. What if he could just go down the block? What if your band could be your life, could be the life of someone down the street because they can go see you play at 7:30 and not have to stay up when they have work the next day? Bob Dylan is an icon, despite all his attempts to deny this, and I think he would recognize and appreciate Boon’s casual yet heart-stopping shout: Mr. Narrator! What I choose is Bob Dylan to me, not the man himself. You can find a Dylan on your records — “History Lesson Part Two” namechecks Blue Oyster Cult, Richard Hell, the Clash and X — or down the road, at the dive where a local band takes the stage. You could BE that band. Not just folk music, but folks making music for other folks. This is the glory and tragedy of the Minutemen, that they lived this ideal through all its pitfalls and problems for a few years and how it didn’t take Bob Dylan swooping in to take it all away, just a fucking van crash. “The cold comfort that We Jam Econo offers is the notion that genius is fleeting, and the best anyone can hope for is that someone will record it before it fades,” Noel Murray wrote in an appreciation of the documentary.

No one records Llewyn Davis’ solo performance of “Fare Thee Well,” unless you count the Coens themselves. They may be Llewyn’s ultimate Mr. Narrator, or at least Mssrs. Chroniclers, but for all their cynicism and despair they focus on this person as he is about to be obliterated – by Bob Dylan, yes, but for a few hours he’s Bob Dylan to them. Lleywn Davis is never not going to be fucked, because of who he is and when he is; that doesn’t mean what he does has no meaning even as his stubbornness means he’ll never be a part of the new scene being created right beside him. “It was new to us because we were finding out about it, but maybe it’s the kind of tradition Woody Guthrie was about,” an older Watt muses in an interview about the punk scene the Minutemen helped create. “Everyone can’t be born at the same time. Some people were born before, some people were born during, some people were born after, a lot of that is just circumstance. The question is what is to be done where you’re at and how are you gonna do it?”

***

Boon dying destroyed the Minutemen and Watt nearly gave up music. But people from the scene kept him going, like Black Flag bassist Kira Roessler, and a random dude from Ohio named Ed Crawford eventually pestered Watt and Hurley into joining him in a new band, fIREHOSE. They had a decent run of albums, every one dedicated to the memory of D. Boon, and Watt has released several solo albums as well. In particular, Watt formed a trio with drummer Stephen Hodges and guitarist Nels Cline for the 1997 rock opera “Contemplating The Engine Room,” which uses the framework of Watt’s father’s life in the Navy to tell the story of the Minutemen. Jobs on a ship become jobs in a band, with the machinist’s mate Watt hooking up with Fireman Hurley and Boon as the Boilerman. Watt sings about the job he’s doing, which is another way of saying he’s singing folk songs. While Hodges and Cline draw influence from Hurley and Boon, Cline’s spidery guitar sound in particular, they have their own styles and Watt’s basslines are slower and looser than his Minutemen work, and all of this is so much more affecting than a straight replication of that band would have been. And that would have been impossible anyway. This is not “Fare Thee Well,” Watt isn’t saying goodbye, but he’s also recognizing the loss that has defined his life.

We Jam Econo reflects this in its own way. It stops with Boon’s death, forgoing any of the stuff I just went on about, or even the posthumous Minutemen releases, and a limitation of the documentary becomes clear. For all of the movie’s description of and emphasis on the scene the Minutemen were a part of, we hear no music from other bands and only one song — “Ack Ack Ack,” a cover from fellow travelers and influence The Urinals — not written by them. This is clearly in part because of the limited budget Irwin and Schieron were working with as fans; while musicians like John Doe were eager to talk, licensing X’s music would have been expensive (and the lack of other music surely helps keep the doc alive on YouTube in its entirety). But it also works to keep the focus entirely on the Minutemen, showing the life and death of a band in its entirety. And Irwin and Schieron can rework their footage to show the band from a perspective outside the linear time that only leads to one place. A live recording of the great and furious “Little Man With A Gun In His Hand” is played across multiple concerts in order to showcase Boon’s dynamism, it’s technically cheating but the energy of the edits shows the band even better than straight footage would have.

And the final song — save a jam over the credits — is not the final track the Minutemen ever played. That was an encore with R.E.M. covering Television’s “See No Evil” on that last tour; that sounds like an incredible thing to see and hear and play but it is a sad memory for Watt. “That last time I played with D. Boon, I didn’t even play bass, I played guitar,” he recalls, the experience of jamming with legends meaningless compared to the inadequacy of truly making music with your friend. A life cut short and not even ended with the dynamic that helped define it. But while Watt is also playing guitar in that acoustic performance of “History Lesson, Part II,” it doesn’t feel wrong to have that performance close the movie. It’s just him and Boon and Hurley playing their song in a different way, and if it changes while still staying the same, it’s a folk song. Watt wrote the lyrics in the first person about his relationship with Boon but because Boon sings it he turns it around, making it about Watt instead. “Me and Mike, just playing these here guitars,” Boon deadpans, riffing on the performance itself, and Watt can’t hide a snort of laughter. They’re fucking corndogs and it’s fucking beautiful.

Inside Llewyn Davis only covers a week in the life of its subject, but that week stands in for what will likely be a lifetime of missing even the limited success of the Minutemen in their time and Watt’s long career afterwards. This makes it the middle of a triptych bookended by We Jam Econo — that movie’s archival footage shows the life of a band and the interview footage shows its afterlife of love and appreciation;; Llewyn is going nowhere in the purgatory of loss. The last image of Llewyn we see is him staggering out of that alley, watching his assailant catch a cab. Just another person leaving him behind. But Llewyn gets the last word, and in a movie full of goodbyes and farewells he shouts out a brittle yet defiant “Au revoir!” Maybe he’s expecting the circular nature of the movie to be his life, and what could another pounding down the road really do after the shot to the gut of losing Mike? Might as well embrace it. Llewyn is a footnote at best to this world he so desperately wants to be his life, a world that is moving on with a force beyond any punch, but he’s not leaving it, not yet. Watt’s naval rock opera ends with the Boilerman falling overboard and drowning but the work continues and the rising and falling bass riff that opened the album returns at its close, with another day beginning. “There’s always more duty,” Watt sings. “Maybe that’s the beauty.” If he can find it, maybe Llewyn can. Your band is gone but life goes on without the one you love. Until you meet again.