The term “1970s Hollywood” calls up a particular kind of movie, something often dark, auteurist, challenging, and commercial too; it’s used to designate a unique moment when independent cinema got into the mainstream without getting assimilated by it. Movies of the 1970s often have a protagonist who is at best morally compromised and at worst no different from a villain (I really try not to use the word “antihero”), but that protagonist gets threatened, even defeated by forces around him that can barely be understood, much less confronted; these movies were under no illusions that merely being dangerous kept you safe. 1970s Hollywood gave us movies like The French Connection, The Conversation, and Taxi Driver, and in the 1980s, the culture of filmmaking there would change, shifting to market-research-driven large-scale blockbusters. If we want to mark the end of an era, Sidney Lumet’s greatest film, 1981’s Prince of the City, closed the door on the 1970s.

The story resembles Lumet’s own Serpico: rogue cop turns informant, based on a true story (a nonfiction book by Robert Daley). In the first half, Danny Ciello (Treat Williams), one of New York City’s elite Special Investigative Unit cops (the “princes of the city”) goes undercover and wired to build cases against dirty cops and the criminals they work with. His one rule–he’ll never give up his partners–gets challenged all through the second half, consumed with his testimony and the cases that come out of the first. The story keeps spiraling outward, beginning with a straightforward drug bust (that plays into part two) by Danny and his partners, and then encompassing families, bureaucracies, more informants, and attorneys working both with and against Danny.

In its length, scope, and goals, Prince most closely resembles another New York film from ten years later, GoodFellas. Prince doesn’t have the generational scope of Scorsese’s epic, and it’s about cops rather than gangsters (an admittedly telling but minor detail), but both films detail a particular community, with its codes, rituals, and pleasures. (Prince’s cops celebrate a bust with a shave, haircut, and manicure, including whiskey and cigars. This looks and sounds utterly awesome.) Both films use a figure who is both marginal and central to anchor them; they’re more anthropological than anything else, Clifford Geertz’s “thick description” in movie form. (Meals with family and partners play an essential role in both films.) Really the major differences between them come from the differences between the directors.

Lumet’s approach all through his career could be called “theatrical.” He heightens moments, but not the entire film, something that makes this different from Scorsese’s approach. On the commentary for Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, he remarks on the need to not heighten everything, but only to pick a few key scenes. Also, Lumet does this through theatrical methods (staging, performance) rather than the more cinematic methods (off-rhythmed editing, voiceovers, music) of GoodFellas. It’s a set of methods that he learned as a director in the early days of television and used all through his career. You can see it in so many scenes here; one good example is Ciello’s speech to his handlers, just before he agrees to inform. It’s a big, theatrical soliloquy, the kind of thing you could imagine in Arthur Miller, and Lumet blocks it with the handlers sitting down in the foreground and Ciello roving and yelling in the back. What makes it work is that still foreground; these two know that Ciello has already decided but he doesn’t know it yet, and they’re just going to wait him out. Lumet dissolves to the next scene while Ciello keeps yelling; what’s trauma for him becomes just background noise. Now it’s a different location (the apartment balcony), much later, but the same staging and Ciello’s voice is hoarse; he’s been doing this for hours and the handlers are still just waiting. Like so much of Lumet’s work, it’s not subtle and it’s not meant to be, it’s simple and effective.

Elsewhere on the Before the Devil. . . commentary, there’s a great observation from Ethan Hawke: “nobody shoots New York like you do, Sidney,” and he replies “because I don’t do anything.” True or not, that’s what it feels like, and it’s another aspect of this film that feels very 1970s, connecting it to works like The French Connection and The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 (not to mention Lumet’s own Dog Day Afternoon), that sense of New York as it is. One thing that always makes Lumet’s New York feel so real is that he never overpopulates it, never tries to convey “hustle of the big city,” but shows it as a place where people live, work, and act. (Lumet creates two great action scenes here without a shot fired.) That sense of neighborhoods and families with their own history and values runs all through Prince, and makes what Ciello does–betraying his community and code of cops–even more affecting.

Lumet also has a David Fincher-level sense of how to create interior spaces, especially offices, although he doesn’t shoot them as expressively as Fincher. The offices are beaten down, an exact visualization of the cliché “good enough for government work”; the houses of the cops are friendly, the place of families (Lumet understands that families like this keep so many photographs of themselves); the offices and apartments of the Upper West Side lawyers are expensive and always tasteful–you can see in some of the scenes that Ciello gets intimidated just by the furniture. (The thorough sense of 1970s interiors is another point of comparison with GoodFellas.) Part of Lumet’s heightening comes from an instinctively geometric eye, finding some stunning compositions just from placing the camera in the right spot in New York. Writing on Killer’s Kiss, I wondered what Stanley Kubrick would have done if he’d stayed in New York and shot films around the city, without sets. I think he might well have done something like this in 1981, too.

Interior spaces in Lumet sometimes tell the story on their own; remember the long, greenshaded lamp-lit table where Ned Beatty gave his speech in Network? Here, to take just one example, compare the den in the house where Ciello confesses to his partners that he’s turned informant to the courtroom at the end where Lee Richardson cross-examines him so brutally about all his crimes.  Lumet lights and shoots the first one like a confessional box, dark with dappled light, Ciello surrounded by his closest friends. The ensemble plays this dead-on, in that they’re completely supportive without being sympathetic. None of them would do this, but you absolutely stand by the partner who does. The courtroom is almost empty, blank-walled, spacious, and brightly lit; there’s no support for Ciello here and no place to hide, an animal caught in open space.

Lumet lights and shoots the first one like a confessional box, dark with dappled light, Ciello surrounded by his closest friends. The ensemble plays this dead-on, in that they’re completely supportive without being sympathetic. None of them would do this, but you absolutely stand by the partner who does. The courtroom is almost empty, blank-walled, spacious, and brightly lit; there’s no support for Ciello here and no place to hide, an animal caught in open space.

Lumet started in television; like John Frankenheimer and Robert Altman, he was one of the great directors who learned his craft there and brought that kind of immediacy to film. Like a good television director, he knows the value of close-ups and when to cut to them. He’s got some great faces in the cast for that, in all the full-haired and full-mustached 1970s glory. These guys look like New York City cops and attorneys, like this is what the film of The Bonfire of the Vanities should have been in appearance if not character and plot. Since so much of the film requires interviews or interrogations, Lumet can just close in on characters talking and that heightens the action rather than slow it down; we have to keep asking “what will this person reveal? What will he hold back?” and the plot advances on those points.

Lumet and co-writer Jay Presson Allen never make the mistake of having Ciello be the only sympathetic or strong character; in particular, his handlers (Norman Parker and Paul Roebling, who could easily be mistaken for Benedict Cumberbatch in a medium-lit room) are compassionate and nuanced, wondering exactly how far they can push him and, later in the film, how much they can defend him, anticipating the great performances by Scott Bakula and Joel McHale in The Informant! Ciello may rant about the high-priced lawyers, but Lumet doesn’t share that view; he knows these lawyers have their own toughness. That’s most present in Bob Balaban’s character, a ranking Federal prosecutor. Perfectly groomed and dressed, small, even effeminate, he has absolutely no mercy and no ego, never raises his voice (except for one word) or even pauses in listening to anyone: he’s all about his goals and how he can use people for them, and he makes up his mind before anyone finishes talking, gives the next order, and moves on. Ciello can bluff his way out of getting shot, can dare a mobster to find a wire on him, but this is the guy who genuinely throws him off-balance.

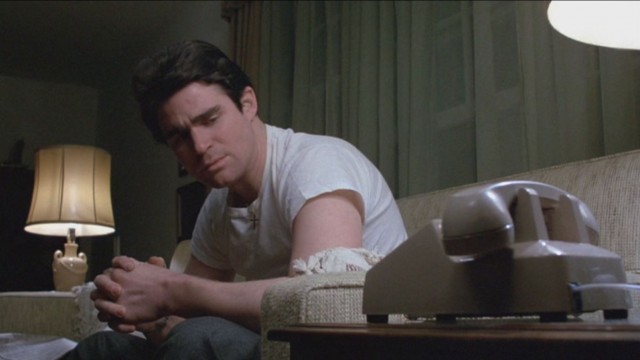

Treat Williams has to hold this film together, as much as de Niro did with Taxi Driver or Gene Hackman did with The Conversation. He does, and in a way that’s all his own. Williams has a broad face and the kind of look that gets called “swarthy”; it makes Ciello look southern Italian, probably second (at most) generation American, a detail that feels right for a 1970s New York cop. He lives by hustling and dealing; Williams gives Ciello a lot of smarts, but there’s also a mania all through the movie. More than almost any other character I can think of, this guy feels like the cop who was almost a criminal, like he got into it for the thrill; think of him as Henry Hill, but from the other side. What makes the performance so moving is the way Williams lets us see how much that thrill now breaks him down. He’s not the stoic hero with a hustling streak, but the other way around, and it’s killing him. Like Lem in The Shield, his body starts failing him as the pressure increases, unable to sleep, bleeding from his gums and loading up on Valium just to get through the day, pacing rooms like he’s caged. When Roebling says that Ciello’s been going out unarmed because “if he’s caught. . .and the verdict is he has to die, he’s decided in advance not to defend himself” the moment lands because that’s what we’ve been seeing in everything Williams does.

Williams was hyped at the time as the Next Big Star (Subcategory: Ethnic), and that he didn’t become one says a lot about how the culture of Hollywood changed. As big-budget movie came to mean “summer blockbuster” and Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer came to be the ideal producers, the stories became simpler, the conflicts within the heroes disappeared. Late in the 1980s, Steve Erickson remarked that “it’s become national policy that doubt is for wimps,” where in 1970s movies doubt was the defining characteristic of the protagonist. Heroes became less compromised and more white, no matter what their ethnic background; the protagonist lost all sense of connection to any neighborhood or history, really to anything but a family. Usually there was barely any connection to that family, too; they existed largely to be placed in jeopardy and then saved. In a single word, heroes became less interesting, and couldn’t be played by someone with Williams’ intensity and internal conflict.

The cast of Prince is uniformly on Williams’ level, playing with depth and sympathy; there are really no villains here, no one who’s bad for the sake of bad. Even the attorney’s who’s the biggest asshole to Ciello gets a few lines at the end where he reveals his history with and commitment to the law. As Ciello’s wife, Lindsay Crouse doesn’t have much to do except react (the perennial problem with this kind of story) but she makes her such a compelling character, as isolated as he is but not allowed the luxury of breaking down. As Ciello’s older partner, Jerry Orbach crushes it. Orbach has no doubts; he knows he’s corrupt and has no problem with that, because that’s not the measure of his worth. He measures that precisely by the number of criminals he arrests and convicts, so it’s no wonder that he’s the one who will never turn himself in. “One tough Jew,” as Ciello sez. When he stands off against Ciello, it’s what drama is: two irreconcilable visions of the good. Orbach makes for yet another GoodFellas connection: the older mentors (Paul Sorvino there) of the protagonist of both films ended up on Law and Order as Chris Noth’s senior partner.

Compared to GoodFellas and so many other works set in this world of cops, criminals, and compromises, Prince of the City does something unique. Lumet’s journalistic commitment to the details of the process, and to what Danny has to go through, raise this above just about every version of this story. That commitment does more than just immerse us in a richly textured world; unlike so many other works, Prince shows us what atonement looks like. It shows more than a world of bad, it shows us the true cost of becoming good. In GoodFellas, Henry Hill’s motivation isn’t ethical. He only testifies as a way of saving his own ass (and his family’s collective ass); as his handler says, “we’re your only choice.” Jumping forward to another great work influenced by GoodFellas, the critical consensus on The Sopranos was that it was about how people don’t change because change is too difficult. However true that is, it’s not dramatically compelling; a drama about the difficulty of change shows people trying to change, and, well, how difficult it is.

Prince of the City relentlessly shows the challenges of atonement, how tangled Ciello has become in corruption and the cost of every move he makes to get out of it. Being at risk of getting killed actually becomes a minor problem for him; as he says, there’s at least a thrill in that. As the film moves on, he gets more isolated from everyone, moved out of his home, moved away from his family into an army barracks (“I’m the first one in prison,” he says); his handlers leave him as they move into other jobs, he gets yanked around by lawyers and transcribers, and then, as the film moves into its last act, the lawyers start turning on him. One prosecutor demands that his assistants go out and get indictments against cops, and “I don’t care if they stick!” because indicting a cop is as good as firing him. Another (played by James Tolkan, a few years before he had to send Maverick to Top Gun) takes bringing down Ciello as his personal mission. It doesn’t feel like justice, but something older, like the reaction of a body to infection: Ciello has disturbed the social order and it’s all moving against him. When another attorney, a scene or two from the end, says “he had no idea how formidable, how inexorable the forces against him were,” it’s no more or less than what we’ve seen.

Ciello’s major, fatal decision wasn’t to inform, but to draw the line at giving up his partners; that means (of course it means) that he’s been covering up a lot of what he did as a cop. (“It’s been so long since I could answer a question without thinking,” Ciello says.) And of course it means he’s going to have to give them up, too, and his journey to that is another necessary part of atonement. Atonement doesn’t just mean confession, it means cutting yourself off from everything that made you guilty, and we watch, step by detailed step, Ciello betray every link to his community of cops and family, to the partners that meant everything to him. We watch, in the agony of Williams’ performance, how much that costs him. We watch how the effects of Ciello’s actions start destroying the lives of others, too; two suicides and a murder follow from his choices. Atonement isn’t just an act of “once I was bad, now I am good”; it has its own consequences and damages, and Lumet makes us ask, as viewers, if the cost of doing good is worth it. (The culture of racism of police will not change until some cop chooses to separate himself or herself from it and testify against it, and their fate will be much worse than Ciello’s.)

A lot of great 1970s works were about heroes alone, but not about a lone man standing against the world. They were about protagonists who made themselves alone, men in communities who wound up stripped of those communities. More socially oriented critics than myself have written about this; I’ll just observe that for all the racial and sexual transformations of the 1960s and 70s, these white men always ended up on their own from their own actions. Fascinating how many of these films–The Conversation, The Godfather Part 2–end with an image of a man alone, isolated, denied of anyone’s trust, and Prince might have the most powerful version of this. (The only equal is the end of one of the TV series it influenced.) It’s the least operatic, most realistic way to play it: no flashbacks, no ripping up the apartment, just a student saying “I don’t think I have anything to learn from you” and walking out, and the cut back to Ciello, hurt, but also accepting that this is the rest of his life now.

If Prince of the City’s style of movie marked an end for mainstream Hollywood, the style resurfaced, soon and unexpectedly, in television. The same year, Hill Street Blues premiered, with so many of the elements that made Prince work: the constant moral questioning, the range of the cast, the verisimilitude of the setting, and the sense that there just aren’t any permanent victories. Hill Street never dominated television, and it was a long way from perfect, but it began a tradition that would continue with Law and Order, NYPD Blue, and Homicide: Life on the Street in the 1990s, The Shield and The Wire in the 2000s, and True Detective in the present day. So much of the style and moral universe of these shows, argued by myself and many others to be television’s finest, call up the great films of the 1970s. Prince of the City can feel to contemporary viewers like the just-discovered missing link between them.