The Stepford Wives (1975) and The Love Witch (2016) use an early-70s setting to look at how heterosexual relationships reveal fantasies of domination and control, fantasies that are shaped differently according to gender. It’s certainly not coincidental that both films disclose the limitations of these fantasies.

The Stepford Wives has become a term to describe certain types of women who mindlessly obey their husbands. The lasting relevance of the film, based on the novel of the same name, depends less upon the surprise of the ending, where a woman discovers the secret of the town—all of the women are actually robots, and she’s next—and more upon how the ending provokes the audience by raising the question: if men could create perfect women, would they do so?

Like many horrific scenarios, The Stepford Wives delivers potent social criticism. What makes women imperfect, for certain types of men, is that their minds sharpen, while their bodies age. Getting rid of their real minds and bodies and replacing them with artificial ones, is one effective way of solving the problem.

All of the clues that lead to the ending have to do with how women can be dominated and controlled. The wives of Stepford, whose programmed vocabulary is limited, speak in advertising clichés about their domestic roles, which include pleasing their husbands in every way. When a woman is replaced by her robotic counterpart, she gives up all other pursuits: even playing tennis, hardly a revolutionary activity, is considered a needless distraction from her main purpose.

In the opening scene, Joanna, with her family, prepares to emigrate to the upstate New York suburbs. She already misses the city, which afforded her any number of opportunities as a photographer. But Walter, her husband and an aspiring social climber, can only see the possibilities that Stepford offers—and genuinely feels that over time Joanna will adapt to the change in locale.

Because our view of Stepford is mostly through Joanna’s eyes, which register how strange the place is—at times, it feels like a community theater staging of a play written by Miss Manners—we catch on rather more slowly that the male technocratic leadership enforces an oppressive regime of social conformity. Walter, at times, acts distraught, drinking more heavily, as he is privately briefed on Joanna’s outcome.

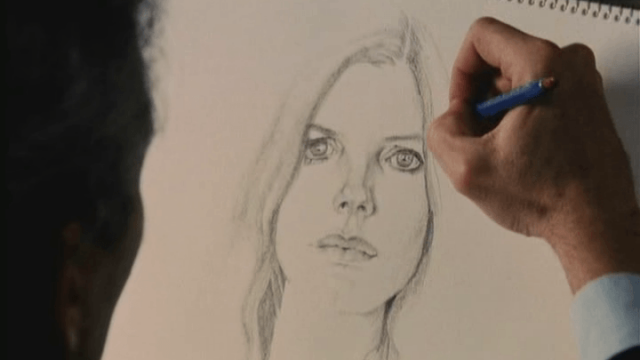

Walter’s gaslighting of Joanna when she insists on their leaving Stepford gives her time to see how she’s been studied by the men who are designing her replacement, literalizing the idea of the male gaze that objectifies women. And the last scene, featuring the robot version of Joanna, in the supermarket allows the camera to take in an African-American couple, newly arrived to Stepford. We are left with a prototypical moment of intersectionality.

Although the opening minutes are striking—Joanna looks at herself in the mirror with funky bathroom wallpaper in the background—the visual design seems pale and drab once the setting shifts to Stepford. In this regard, it’s telling that the film was not made more complex to further explore the issue of multiple personalities. Of course, in Stepford, this issue has a discomforting resolution.

Unlike its 2004 tone-deaf remake, the film holds up by maintaining a satirical tone, and refraining from too much overt irony. What does date the film is that now we realize that social pressure, rather than technology, is more easily applied to coerce women into keeping themselves, and other women, in line.

The image of the wives of Stepford is reversed in The Love Witch. Here, it becomes a way to lure men to their downfall by granting them their fantasy of the perfect woman. Early in the film, Elaine lectures her friend, Trish, on the virtues of giving men everything they desire. That this lecture takes place in a tearoom straight out of the Victorian era assures us of the loopy manner in which The Love Witch intends to answer The Stepford Wives. Elaine’s submissive pose is a ruse. When she’s back in her apartment, she crafts spells that make men fall in love with her.

The image of the wives of Stepford is reversed in The Love Witch. Here, it becomes a way to lure men to their downfall by granting them their fantasy of the perfect woman. Early in the film, Elaine lectures her friend, Trish, on the virtues of giving men everything they desire. That this lecture takes place in a tearoom straight out of the Victorian era assures us of the loopy manner in which The Love Witch intends to answer The Stepford Wives. Elaine’s submissive pose is a ruse. When she’s back in her apartment, she crafts spells that make men fall in love with her.

Elaine, however, gets bored with men easily, and, once she walks out on them, they self-destruct. In a cruel twist, one of her victims is Trish’s husband. As the death toll mounts, Griff, a comically righteous police officer is assigned to the case.

It’s not, however, the story that really matters; it’s how the story is told (again the mirror opposite of The Stepford Wives). Writer and director Anna Biller juxtaposes the witchcraft narrative against the generic conventions of romantic melodrama, which creates an engaging friction. For one, it prevents a reductively feminist reading—almost as if Biller is saying that sexual politics are far from easy to chart, much less film.

It would also be wrong to conclude that witchcraft is the feminine counterpart to science, because witchcraft is not an escape from patriarchal attitudes. Elaine’s control mania is shown to have derived from a male-led initiation rite. A stop along the way to a Renaissance festival (a scene which has been criticized for the time it takes up in the film) reminds us of how love has been historically both idealized and commodified.

Some viewers might be inclined to dismiss the film due to its overly dramatic gesturing and stilted dialogue. But the joke is on them, because the film is actually making fun of the idea that people don’t take romantic melodrama seriously as other genres. While the film reflects a self-awareness of its setting, its characters don’t. Therefore, it’s more accurate to say that the film subverts audience expectations; of course, Elaine and Griff fall in love—yet, because of the downward trajectory of romantic melodrama, the outcome must have a tragic tone.

The Love Witch is a playful warning that once we are willing to resort to trickery to find a partner, we’ve already given away far too much of our souls. Rather than a shortcut to happiness, it leads us to becoming criminals, taking what is not ours. The Love Witch is not a revenge fantasy directed against the male villains in The Stepford Wives; rather it suggests that when love is a battlefield, nobody wins.

Just as The Stepford Wives asks what real women are; The Love Witch asks what real love is—as opposed to its funhouse reflections, of which Biller would remind us that her film is one, a product of the dream factory.