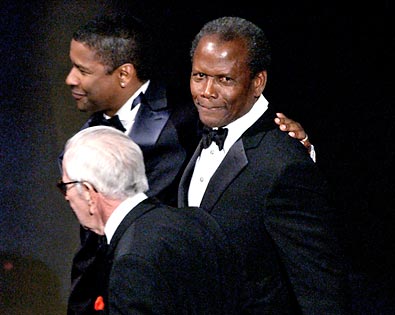

It’s no secret — to those paying attention — that Hollywood has a race problem. And this is not a new issue. In its past century of existence, the American popular film industry has generally only seen fit to have a single black leading man at a time (with the exception of comedians, who are somewhat more accepted). In 2002, when he won his first (and to date, only) Best Actor Oscar, Denzel Washington raised his statue in the air and said “I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney,” referring to that year’s Honorary Award recipient, Sidney Poitier.

These two major stars, two generations of respected and desired black manhood on film, Sidney and Denzel — they stand as the benchmark by which all black male actors are judged against. When a young black actor, a Michael B. Jordan or a Chadwick Boseman, bursts onto the scene, the hope (on behalf of Hollywood) is that they can become “the new Denzel,” a black star who can launch African American-themed films like Malcolm X and The Hurricane as easily as he can launch more standard Hollywood vehicles like Flight or The Book of Eli. But often, these actors fall short: victims of institutionalized, narrow-minded racism as much as anything.

Before Denzel was Sidney. Sidney Poitier, the Bahamanian immigrant who became Hollywood’s first major black star, the first black male actor to win an Oscar, the first black star who was allowed to romance white women on screen, who marched with civil rights leaders in real life while he broke down barriers onscreen.

But before Sidney was James Edwards.

No one remembers James Edwards. But he was the Sidney Poitier Experiment when no one knew who Sidney Poitier was. There were black leading men — of sorts — before Edwards.* Paul Robeson, one of the most amazing men of the 20th century, a Renaissance Man for a distinctly non-Renaissance age, was a standout All-American football player, a singer with an impressive basso voice, a political activist, a Broadway star, and, yes, a Hollywood leading man. In films like the Eugene O’Neill adaptation The Emperor Jones, where he played an American gambler who winds up as the leader of a Caribbean country, he dealt with themes of race, while in more mainstream fare, like 1937’s adventure-in-darkest-Africa escapade King Solomon’s Mines, he got top billing over his white co-stars. But Robeson was such a remarkable individual that “Hollywood star” was far, far down on his list of accomplishments, and he never fully occupied the role of “actor” as did someone like Clark Gable or Spencer Tracy.

*Those readers unfamiliar with the “race films” of the 1910s should acquaint themselves, because the represent a truly interesting phase of American cultural history. With black audiences in mind, these independent made films featured African-American casts and crews, and concerned themselves with African-American issues and interests of the day. But being made outside the purview of Hollywood, they’re worth mentioning but not truly relevant to the discussion of the black Hollywood leading man.

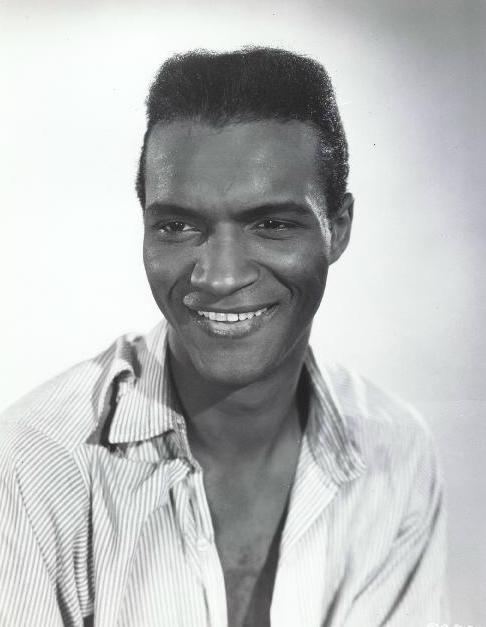

Edwards was different. He seemed to be a natural movie star. He was handsome, classically so. With the obvious difference of his race, he looked like a 1950s leading man, like Rock Hudson or Charlton Heston. He had a great voice. He had natural charisma to spare. In 1949’s The Set-Up he practically steals the movie in a few short scenes as a confident young prizefighter whose exuberance and force of will contrasts with the tired, sad sack white protagonist played by Robert Ryan.

Image source: www.whenmoviesweremovies.com/hoosieractors2.html

Image source: www.whenmoviesweremovies.com/hoosieractors2.html

That was Edwards’ first film. His next was Home of the Brave, a pre-integration drama about a black soldier facing prejudice from his white brothers-in-arms. The role would anticipate Sidney Poitier’s future onscreen persona of the black man who is the first to enter a chosen white field, and encounters hatred along the way. The film was controversial, but big things could have been on the way for Edwards. He did more war movies, like Bright Victory and The Steel Helmet. He seemed to have what it took to be a leading man, even in 1950s Hollywood.

But something went wrong along the way. Edwards struggled with alcoholism, which didn’t help his career, but his alcoholism also seemed to derive partially from the pains of being talented in an industry that saw him only for his race. He told his friend, fellow black actor Woody Strode ” Woody, you’ll never be white. Don’t try to become part of their society.” Whether due to racism, Edwards’ own personal issues, or most likely, a combination of the two, James Edwards did not end up becoming the First Sidney Poitier.

He never lost his talent, though. Even while performing in films and TV shows below his talent and demeaning to his personage, like Tarzan’s Fight for Life or Ramar of the Jungle, Edwards was still able to find time to continue stealing scenes in quality movies. In 1962’s The Manchurian Candidate, he plays a shell-shocked Korean War vet brainwashed by a Communist conspiracy, and delivers the film’s best, and most chilling rendition of “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.” His swan song was 1970’s Patton, where he played General Patton’s longtime driver and companion. It’s a small part. But he gets to play one great scene alongside George C. Scott, where the two reminisce on their lost youth and their shared past as old cavalry officers. He died before it was released. He was only 51 years old.

While Edwards’ star declined, the career of Sidney Poitier soared. Poitier, to both black and white audiences, became a symbol of popular black masculinity, every bit the equal in charm, strength, and intelligence to his white counterparts. Poitier broke through with 1955’s Blackboard Jungle, and had a string of successes both critical and commercial until he decided to take a break from acting in 1977. This left an apparent vacuum that had to be filled.

Howard Rollins Jr. briefly seemed to fill that vacuum. A stage actor, Rollins made his feature film debut — and a hell of a debut it is — with 1981’s Ragtime. In the film — an Altman-esque portrait of America circa 1905 — Rollins plays Coalhouse Walker Jr., a ragtime piano player, who is smart, educated, confident, and dedicated. He is, in short, everything that a black man is not supposed to be in Ragtime-era America (or Ronald Reagan’s America, for that matter). The film slowly begins to orient it’s narrative around Rollins, and in its final acts, the story takes a fascinatingly anachronistic turn. Coalhouse Walker becomes a proto-Black Panther, a Malcolm X in an era of blackface minstrelry, seeking revenge on white society by barricading himself in J.P. Morgan’s library, armed with guns and bombs, and threatening to blow the thing to high heaven if his demands are not met. In the end, Walker cannot outrun the dictates of society, and is shot down in the streets, but not before he prays to God, eyes filling with tears of futile anger, “Lord, why did you fill me with such rage?”

Ragtime should have put Rollins on the map. In it, he was alternatively charming and intimidating, playing a character both of his time and against it. It is a wonderful performance. But Rollins was never able to make it all the way in Hollywood. While some members of the black community petitioned for him to play Malcolm X in a pre-Spike Lee feature film, the industry rarely knew what to do with him. He had the leading role in the 1984 drama A Soldier’s Story, where, like James Edwards before him, he played a black soldier encountering racism from whites in the army. It would be his last leading role in a cinematic film. The film was a sign of things to come as well, since the most memorable part in the film is not Rollins’ officer investigating a murder in the South, but a young Denzel Washington’s fiery baseball player who holds secrets. While one star rose, Rollins’ star was falling. Soon, he moved away to television, playing the same role Sidney Poitier originated in In the Heat of the Night for a TV spinoff of the same name. He seemed a natural fit for the part, but sadly, real life issues got in the way. Rollins spent time in and out of jail of driving under the influence as well as cocaine possession, and was fired from the show.

His career never really recovered. After being diagnosed with AIDS in 1996, he only lived for another six weeks before succumbing. He was 46 years old. It’s hard to watch Ragtime with this information in mind and not see Howard Rollins Jr. as having much in common with Coalhouse Walker Jr. — to think about the young black man with so much promise and potential, who is snuffed out by an unfeeling world that has no care for him when he’s no longer entertaining.

And so, with this Martin Luther King Day, let us in the cinephile set remember Howard Rollins Jr. and James Edwards. Let’s remember Ragtime and Home of the Brave. And let’s find a little time in our day to remember the countless black actors — male and female — who never got their shot at the big time, because of what they looked like. And let’s take the rest of the year to support black filmmaking and black artists who don’t get more than their one chance for glory.