The Conversation on the Solute

Avathoir and wallflower discuss the first “Cycle” of American Vampire

Installment 5: The Fearless Vampire Killers

Warning: Like all Conversations, this contains Spoilers. Read at your own risk.

Avathoir: This is the first story arc of significant difference from the series thus far. We have our first story were neither Pearl or Skinner are main characters, or even appear (Dream sequences don’t count). We have our first artist who has no similarities to Rafael Albuquerque in Sean Murphy, and perhaps most importantly, our first hints at the Vassals of the Morning Star’s motivations and a hint at the lore and the myth of what will be appearing in the coming volumes.

Wallflower, reading this arc, what struck you most about the differences present here? How also, may I ask, do you think it adds to what story Snyder is telling, both with this story (European instead of Pacific, a new generation instead of the first with Felicia), and the larger myth arc?

wallflower: One of the things I enjoyed about this, and was different from what came before, was the sense of (to quote Snoopy) “in chapter two, I tie all of this together.” By having characters like Felicia, the Vassals, and most movingly, Cashel’s son keep going past their introduction, it gives the feeling of a larger world and a larger struggle. It’s always good to see that a creator hasn’t forgotten his creations. Also, this was the first story where I got a sense that an endgame was coming, and this wouldn’t just be an ongoing series of episodic adventures like The Walking Dead. I also enjoyed it because come on, what the hell kind of WW2 story is it if ya don’t have Nazis?

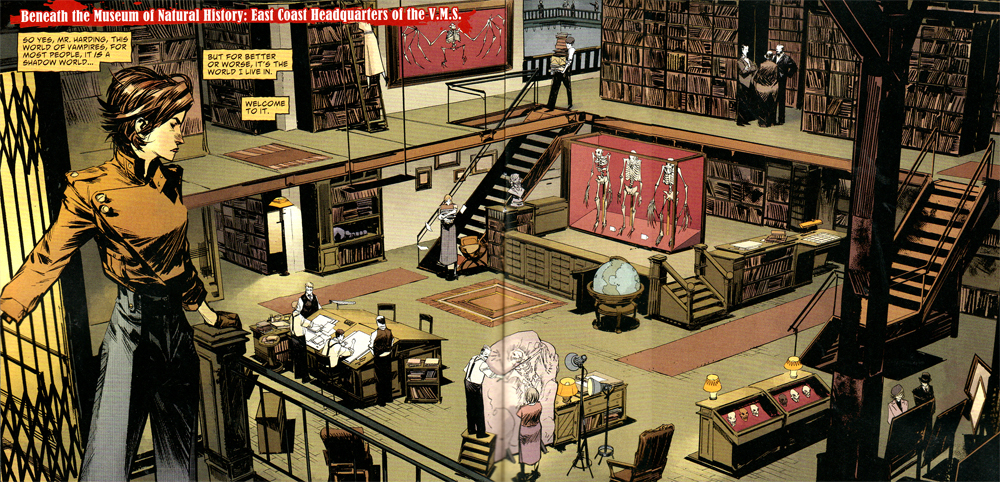

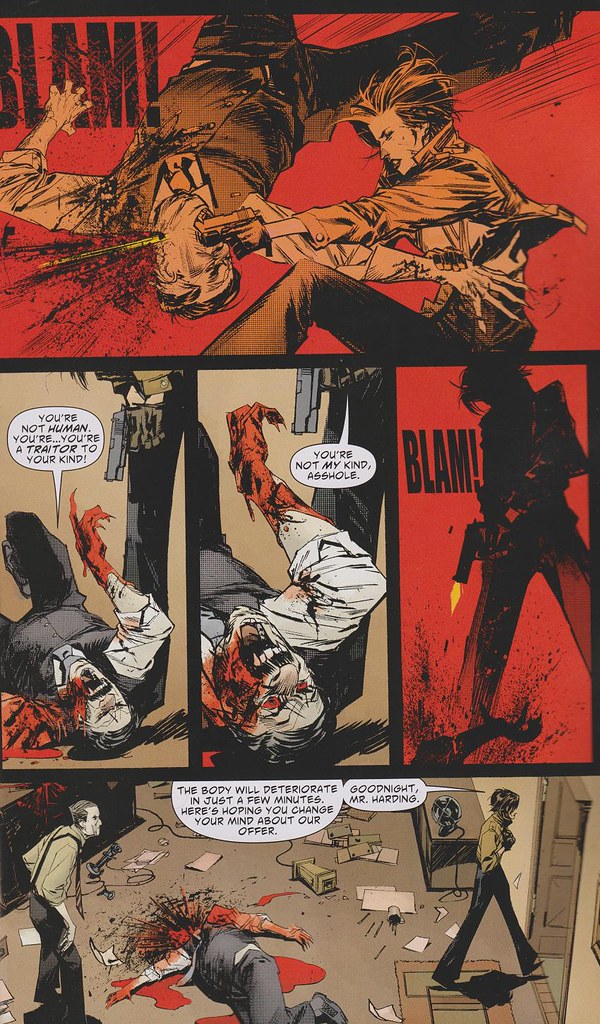

Sean Murphy gives “Survival of the Fittest” a very different look than “Ghost War,” or indeed any other installment to date. That makes sense; we talked at the very beginning of this Conversation about the visual differences between the American vamps and the Eurovamps, and now we’re back in Europe (or as some still call it, the Old World). Murphy favors more blocky, painterly compositions and more classical paneling than the dynamism of Ghost War; his lines are more jagged than Albuquerque’s fluid drawings. (Simon Bisley’s work, particularly on Warren Ellis’ Global Frequency, is like this.) It calls up the image of a much older, more static, even somewhat inbred world; some of his drawings of the Nazis look like George Grosz’ paintings. He uses painterly effects, giving the German scientist Dr. Erik Pavel a simple profile; in his first appearance, he looks almost distant rather than small. Most noticeably, Murphy restricts his palette to browns, blacks, and desaturated reds. The blue of sky, the yellow of sun, and the green of plants are almost gone, so there’s nothing of nature; because we lose our sense of color in the dark, this makes the entire story feel like it’s taking place at night or indoors.

That makes sense for something that’s coming clearer all the time here: this is almost entirely a story about characters who are at least part vampire, and I suspect that’s one of Snyder’s major contributions to the genre. Vampire hunter Felicia has some of Skinner’s blood in her (and he shows up in a dream to remind her); vampire hunter Cashel has his vamped son, Gus. Like The X-Files, Snyder scuffs up the bright line between human/not-human. He doesn’t use it as romantically as Joss Whedon did, but treats it in a much more practical way, as a question of loyalty. Where is your community? Can other vampires smell who you are? Snyder’s commitment to the adventure genre makes these questions absolutely thrilling, because the whole story can turn on them.

Avathoir: How right of you to say “Adventure” here, because far more than “Ghost War”, “Survival of the Fittest” is an adventure story. The first one was very much a horror story in a lot of ways, as well as a love story, Samuel Fuller’s version of Alien with some Before Midnight sprinkled in. But “Fittest” is one hundred percent pulp. Hawks and Hitchcock and pulps abound here, from the locale of icy European mountains to the photon cannons and Tesla coil(!) that helps with the climactic escape. Cashel sings the goddamn Star Spangled Banner as he makes his last stand: you don’t get much more pulpy.

I also think you’re very right that the key isn’t just art and color with Sean Murphy as the main difference between Albuquerque, but his layout style and pacing: Albuquerque panels bleed into each other, have a watery property, they slip and blend together very quickly, bleeding from one image to the other (J.H. Williams III has made a career out of taking this effect and pushing it to its limits, and has deservedly been awarded for it). Murphy, in contrast, is more of a traditionalist. Though he’s got a clear manga influence in his sketch-like compositions and dynamics, panels are clearly meant to be read one at a time, the gutters noticeable, each image existing in its own world. It’s not a bad thing at all, but it’s a very marked contrast to what’s come before, which given what transpires is appropriate.

I digress, though. Even more than a pulp adventure, there’s the family element to this story. Cashel is desperate to get his son devamped, and Felicia is still very much a child, one whose influenced by the parent who isn’t there (Jim) and the one who made her what she is (Abilena). As much as this story is about thrills, it’s also about what comes next when you find people you love, such as Cash and Felicia (who only get one real moment together, but what a moment) and at the very end, Felicia becoming Gus’ mother, since Lily couldn’t ever get the chance. Cashel’s soliloquy on Gus’ condition (“He’s just stuck”) remains one of the best depictions of fatherly love I’ve seen in comics, and maybe literature in general.

Stuck is also a good word to describe what’s could have been going on until this moment. As you said before, this is the first evidence that things are starting to converge, to tie together, and though we aren’t finished with that (I hate to say this, but even though we get “resolution” in these first six volumes, there’s still a lot that isn’t answered), we’re starting to see things are beginning to fall into place. There are three big developments here: one, we learn the name of the Eurovamps species (Carpathian). Two, we find out that there are some VERY NOTICEABLY DIFFERENT vampires that the humanoids we’ve encountered. Three, we learn a lot more about Felicia.

Before we talk about the first two, though let’s address the third. Felicia is very different than Pearl. You could even say they are inverses of each other. Pearl, at the start of her story, is a young woman who’s never known violence, and becomes someone who is very much a part of a “Darkness” so to speak. Felicia, in contrast, is a girl who has never known peace, and becomes a mother. It’s very interesting for me how she chooses to leave the Vassals with Gus, how she chooses to break the cycle her mother started. What do you think of Felicia’s arc in this story, in regards to this and your own opinions?

wallflower: Felicia’s arc moves from being solidly with the Vassals to leaving them, and that’s as much about the Vassals as her. Snyder bookends her story with the identical line: “For better or worse, this is my world. Welcome to it.” The first time it shows her as being clearly one of the Vassals (she delivers it in their headquarters); the second time it shows her as being outside of it. Your description of her story as being the inverse of Pearl’s is well-taken, because both of them are on the human/vampire and peace/violence borders, just moving in different directions.

From the first volume, Snyder has played the theme of individuals and organizations. What defines the American vampire is what, for so many, defines America: the primacy of the individual. From the first volume, Snyder has played the characteristics of the individual against all forms of organization: police, country, city, history. Like Pearl, Felicia begins in motion, and it’s in this volume that she discovers the same thing Pearl lives: she can never have a true home, there can never be an organization in which she’ll belong. In American Vampire, the only organization you can hold to is family. All larger, more complex organizations are wrong for you, when they’re not actually corrupt. We saw in “Ghost War,” by the way, that the Vassals have an agenda that they don’t reveal to Pearl. It’s not clear whether or not they are using Felicia the same way, but they’re certainly capable of doing so. That suspicion of organizations is a deeply American cultural value, too.

So it makes sense that in addition to taking Felicia on a moral journey to walking away from the Vassals, Snyder also takes her on a spatial and even temporal journey back to Europe, to both a much older organization of vampires (the Carpathians) and to the oldest, most monstrous vamps of all. That classical style of Murphy’s, by the way, really pays off with the Stadium o’ Carpathians that closes part 2 and opens part 3. It’s a great use of the vertical paneling and looks truly monumental and dominating. (Eat shit and die, Triumph of the Will.) There’s also a great, Lovecraftian touch of horror with the ancient vamps, when Pavel the scientist realizes that the mold that keeps growing on an enormous statue’s shoulder isn’t mold, but scabbing. As ever, Snyder keeps expanding and deepening the vampire story here, which is one of the things you can do in an epic work like this.

Avathoir: We really need to talk about the deepening story here. First, there’s the fact that outside the Gaelic-Prime Augustus and Pearl, Skinner, and Calvin, we’ve only met Carpathians. This the dominant strand of vampire, (the panel where it cuts to them cheering after Pavel says this still haunts me), and yet…they’re curiously weak, you know? They’re weakness is the laughably common wood, and they can’t do outside in the sun, as opposed to the other vampires that we see. Even the Ancient Vamps can do that, though they burn very slowly. It’s curious how exactly they became the dominant force (I know why, but I’m NOT GOING TO TELL YOU MUAHAHAHAHA) but it DOES tie very much into the idea that something is going on that we’re not being told, that the Vassals have a very clear understanding.

Which brings us to the Ancient Vamps. What was your reaction upon seeing them? I remember reading this for the first time I was a little skeptical, thinking “Come on, Snyder, you really went there?” But rereading it I find it a really excellent shade to the mythos. They seem to be almost mythical, and like the head Nazi said “Something you knew existed all along”. The fact that one of them calls Felicia “Chosen One” is also something curious. It suggests that we’re going to move even more into “Mythic history”, that what lies ahead is not going to be something so tied to the (relative) realism we’ve previously encountered. What do you think?

wallflower: You almost have to go mythic when you write about vampires. No matter how much you try to contain a vamp story within genre, whether it’s witty high school drama (Buffy), L. A. noir (Angel), or science fiction (The Strain), vampires will lead you into that mythic, primal territory. “Something you knew existed all along” is another way to describe an archetype, so it’s natural, even necessary, that we go into the ancient past with vampires, into the world of the primal. (Part of what made Angel so fascinating was the way Joss Whedon and his team negotiated that turn into myth.)

Pulp fiction, especially comics, are a great way to explore that kind of myth; really, it gives you a chance to invent your own myths and archetypes. (See: Neil Gaiman.) As we come to the halfway point of this cycle, Snyder looks to be developing a Whedonian world, where there are ordinary people, mythic figures, and ordinary people who have to cope with being mythic figures. (There’s also a covert organization that’s covert in its motives, even from those within the organization, comparable to the Watchers or Wolfram & Hart.) The challenge of this is to do it in a way that’s somehow ordered and satisfying. Stories about everyday life can have the messiness of everyday life, but myths need a simple, clear structure to endure. American Vampire doesn’t have to come to a resolution–I’m not expecting that–but the elements do need to come together into a larger design.

The American Vampire Conversation will continue with Installment 6 “The Unforgiven”, Installment 7 “Drive”, and Installment 8 “The Anatomy of Melancholy. Stay tuned!