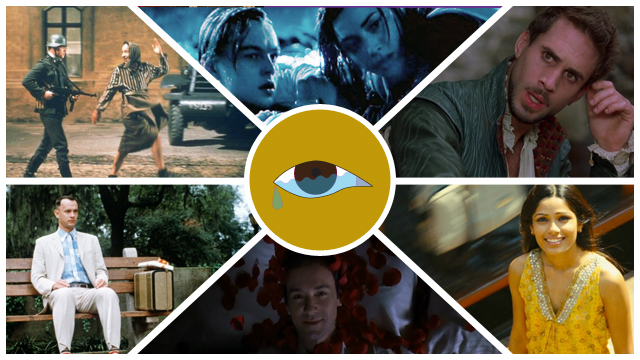

The English Patient, Life Is Beautiful, American Beauty, Slumdog Millionaire, Titanic, Shakespeare in Love, Forrest Gump

All of the above movies are either Best Picture or Best Foreign Language Movie winners at the Academy Awards, and most of them have had a backlash they haven’t fully recovered from. At first glance, these movies have little in common, but the main link that binds them is a willingness to manipulate emotions through cinematic technique. Movies that trade in emotional manipulation over intellectual thought or distanced observation tend to fare better in the months after release but worse in the annals of time.

During the first viewing of an emotional movie, the common viewer will give themselves over to the ride. They’ll laugh when they’re told to laugh, cry when they’re told to cry, feel everything that the movie tells them to feel. If a movie succeeds in manipulating the audience into believing they are watching a quality piece of art, then the movie has done its job in the immediate. Art is meant to make us feel as much as it makes us think. But, when the emotional manipulation covers for a certain intellectual shallowness, people have a delayed reaction against it. Moreso when the emotionally manipulative movie gets universal praise, and god forbid it gets awards.

When American Beauty was released in 1999, critics talked about the film in the hyperbole. Rotten Tomatoes gives it 88% fresh. The New Yorker called it an “amazing and impassioned fantasia” ending with “a vision of the sublime.” Roger Ebert gave it four stars. The LA Times said, “Beauty is a blood-chilling dark comedy with unexpected moments of both fury and warmth, a strange, brooding and very accomplished film that sets us back on our heels from its opening frames.” Even though the cracks of the movie were showing, Scott Tobias said the film was “so exhilarating it hardly matters.”

By 2001, after American Beauty had won the Best Picture Academy Award, the reputation of Beauty left much to be desired. Slant magazine called it a cartoon, commenting that it doesn’t age well. This week, Tobias wrote that he is not the person who would have written the glowing review from 1999. It’s not the movie that changes, it’s the person’s reaction to it. Most often, however, these sea changes happen to films that grab you by the heart and not by the brain.

Emotional reactions rarely get deeper the more you hear the same story. The more you hear the story, the more you start to think about it, and the more you think about it, the more you look for the flaws or meanings. An initial gut wrench of a thrill ride might dissipate on multiple viewings, leaving you to ponder the meanings of what you’re watching. In terms of Titanic, you’re left with a shallow movie about class and death without exploring the societal implications of either. Nor does Titanic explore the motivations of the wealthy whose greed resulted in the deaths of hundreds of people. But, it packs an emotional gut wrench when the band resigns themselves to sink with the boat.

In a way, the legacy of emotional films represents that of kitsch. They’re seen as sentimental works that excite us without giving anything but enjoyment. Occasionally, they’ll successfully mimic a high-brow sensibility in order to win awards, but are calculated to be easily digestible for mass audiences. Throughout time, these movies will have periods of celebration and derision, never coming to a consensus.

While watching Wild, I found myself remembering how much I enjoyed Slumdog Millionaire when I watched it. Wild grabs people by the gut and heart, practically daring them not to care about the characters on screen. Slumdog Millionaire was a similarly emotionally manipulative movie meant to relay the variety of life in India. When Slumdog won the Best Picture, many people derided it as implausible and the framing device as ridiculous, and use that to criticize the film as a whole. Wild rides similar dangers, with emotional filmmaking hiding a straight-forward self-redemption story with a bootstrappy message hiding behind it. I have a feeling that if Wild won Best Picture, a backlash similar to Slumdog might happen against it.

Which reaction is right? If the art is nakedly about, and succeeds at, evoking an emotional reaction, is it necessarily bad? Is it worse than the preachy movie that makes you think about things without providing an emotional catharsis? I haven’t the answer. I know that if a movie is nakedly about emotional reactions and fails to make me feel anything (looking at you, Gravity), it’s a failure for me. But, that’s a far more personal assessment than what a cultural consensus usually contains.