One of my favourite little things about the 2019 film Parasite is the reveal that Da-song’s nightmares about a ghost coming from the basement actually came from a time he spotted Guen-sae. It’s one of a few reveals in the story that aren’t quite foreshadowing and aren’t quite Chekov’s Gun; there’s no way you could guess where the story was going based on it and the plot isn’t really driven forward by it – Ki-jung is hired as the boy’s therapist, obviously, but he could have had absolutely any mental issue and the plot would have been exactly the same. It’s more like a seemingly weird detail that turns out to have a bizarre but logical explanation. One of the reasons I love it is because it plays into a common fan instinct to look for puzzles to solve, but in a healthy and fun way. One of the earliest Solute-esque internet discussions I ever read that baked itself into my brain was a discussion I saw on the Harry Potter series and the concept of ‘puzzlebox storytelling’. The early Harry Potter books structured themselves as mysteries, in which the hero and audience were presented with questions and the climax was based around a massive revelation, with a lot of information and red herrings in the middle. ‘Puzzlebox storytelling’ became a derisive name for the way the series became bogged down in the idea of the Dramatic Revelation at the expense of an enjoyable emotional journey or a coherent thematic statement – everything was either a Clue or an Answer, with both of those things breaking character, world coherency, mood, or morality for the sake of getting the reader to that ‘aha!’ moment.

Interestingly, these people also castigated readers for falling into the same trap, and for creating a vicious cycle of meaningless bullshit as they dove into the possible literal exploration for random specific statements and actions as opposed to trying to understand the moral and ethical drives of the characters and/or forming a personal moral reaction to the events of the story. These people framed reading as an ethical act – not in the sense that picking and choosing what you read makes you a good person (a concept beloved Soluter Ruck Colchez has loudly and correctly objected to), but in that a reader must actively interpret the morality of a story for themselves. They were roasting JK Rowling about a decade before it became cool, and not just for the reasons that are popular now (her not-as-radical-as-she-believes politics, the bizarre facts she generates about her fictional world) but for the way her statements often rewarded speculation at the expense of interpretation. One thing that always stuck in my head was how they spotted a fan questionnaire done before the release of the final book, in which she praised one person for creating a theory about how the magic in one particular aspect worked whilst shutting down a child’s theory about how Dumbledore might still be alive and assuring him he was definitely, unequivocally dead; they were outraged that she would use the one hand to reward someone for literary trainspotting and use the other to slap away the very real emotional experience of dealing with the death of someone you care about. They often discussed how this showed up in her writing, not just in the (increasingly inane) mysteries but in the way Rowling would keep slamming down specific interpretations of the characters. They were equally disgusted with readers who accepted her interpretations at face value instead of digging into the morality of the series.

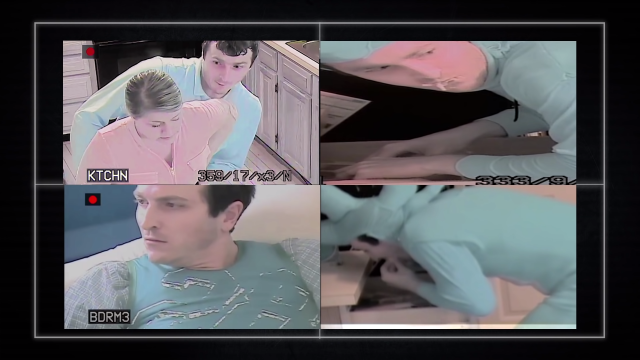

It was both an expression of muddled thoughts I’d had about fiction in general, and a deep influence on the way I write fiction and about fiction. It’s an understanding of reading as a spiritual experience grounded by a practical aim, one that elevates both storyteller and reader into divine beings. At the same time, I can’t help but feel now that the problem isn’t aims but competence. Rowling isn’t really bad for wanting to write puzzlebox stories, and readers aren’t really bad for enjoying lore and solving puzzles. The Harry Potter books became messier and more poorly structured as they went on, but the fact that the earlier books were so entertaining makes me think that Rowling’s ambitions just went in a direction counter to her talents – that we missed out on a truly great work because she did not continue down her mistaken path but tried going down a dead end. There is some spiritual thing hiding at the other end of puzzlebox storytelling, and just because Rowling couldn’t find it doesn’t mean it’s not there. Equally, while I’m less invested in sifting through the literal details of worldbuilding to create elaborate conspiracy-theory-esque explanations, I have enjoyed just enough of them to see their value. Perhaps the best example I can think of offhand is the [adult swim] production This House Has People In It. The surreal nonsense is fun enough on it’s own, but I also watched a video that dove deep into the mythology of the short and went through the extra details hidden within the website related to it, explaining the links between everything. The final conclusion was hardly that profound, but there’s both the sparks of interesting points brought up all throughout both videos and a genuine pleasure in the paranoid domestic horror we’re presented with that only gets weirder as more information is thrown at us.

A great puzzlebox story is an elaborately constructed experience that unfolds before the audience like a Rube Goldberg machine. My first thought when starting this essay was that perhaps Parasite shows that it’s something best enjoyed as a spice to a real story, but I’ve talked myself into believing a whole-ass story can be made out of the concept. If we look back to those early Potter books, part of the reason they work is because they’re absolutely drowning in information, whether it relates to the final revelation or not. This disguises the information in red herrings and blind alleys. Of course, the fact that the characters are always reacting to the information they receive also helps; it drives their choices, the fundamental building block of all good storytelling. This is also visible even in the main short of This House Has People In It – much of the story’s meaning comes from the bizarre and bizarrely human reactions of the family to the sight of Maddison phasing through the floor, and the information hiding deeper in the puzzlebox reveals a wider world of behaviour that’s strangely comprehensible. Much as a comedy can get away with anything provided it’s funny, a story can get away with anything provided it shows people making meaningful decisions.