Out of every movie, across the whole history of Hollywood, it is perhaps Gone with the Wind that has cast the longest and most imposing shadow.

Gone with the Wind is no Forgotbuster. No, no – today we’ve come not to bury nor praise Gone with the Wind but to instead evoke the memory of a film called Raintree Country. The odds are that you haven’t heard of Raintree County. Its legacy is mostly forgotten – laid somewhere in a snug space above Band of Angels but considerably below Jezebel. More on that later.

But to understand Raintree County, you have to understand Gone with the Wind. Y’see – Gone with the Wind’s romanticized and aesthetically amplified portrayal of the Southern aristocracy and slave-owning class of the Civil War era was a story, a myth, but a very appealing one to a lot of people. The beauty of the filmmaking, the brilliance of Vivien Leigh’s performance, and the capital-R Romantic nostalgia of the narrative* all struck a chord with audiences in 1939, and the movie continues to do so today. The public rewarded the filmmakers by making Gone with the Wind the single highest grossing film of all time.

Raintree County is Hollywood’s attempt to play the Gone with the Wind tune yet again. But with crucial differences.

The film opens to the dulcet sounds of pioneering black pop singer Nat “King” Cole, singing the part-bombastic, part-gentle “Song of Raintree County.”

“They say in Raintree County

There’s a tree bright with blossoms of gold

But you will find the Raintree’s a state of the mind

All a dream to unfold”

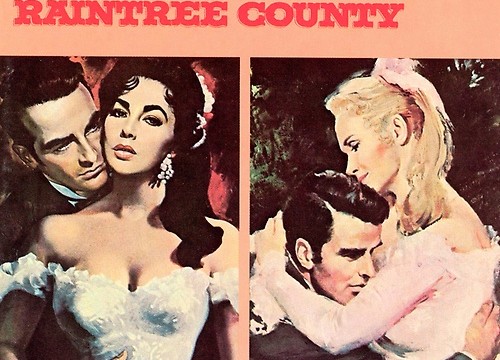

From there we gather on the scene of Raintree County, Indiana, in the 1850s, a century before the film’s 1957 release. Graduating high schooler John Shawnessey – Montgomery Clift playing too young – juggles the affections of two competing sweethearts: sweet hometown girl Nell (Eva Marie Saint) and the mysterious and passionate Susanna (Elizabeth Taylor), a Southern belle visiting from New Orleans. As the suspiciously-old looking students of Raintree County are tutored in the ways of idealism and romanticism by flamboyant schoolmaster Professor Stiles (Nigel Patrick), young John hatches the idea of finding the mythical “Raintree” planted years earlier by Johnny Appleseed, a tree whose properties are mysteries yet whose legend continues to bloom.

Amidst all this picturesque playfulness, the seeds of discord are beginning to be planted. With the country only a few years away from what will be called the Civil War, North-South tensions grow, especially in relation to Susanna, whose wealthy Louisiana slaveowning family sticks out like a sore thumb in the more egalitarian-minded Indiana**. When John is told that Susanna is pregnant with his child, the two – representing the uneasy relationship between North and South – marry and move down to Susanna’s family plantation in New Orleans.

In this segment, the story of Raintree County goes from quaint Midwestern folksiness to full-on Southern Gothic. As it turns out, Susanna’s mother was one of those classic Southern belles who went madder than a wet hornet and burned to death years earlier in a mysterious house fire, which also claimed the lives of Susanna’s father and his black slave mistress. Liz Taylor’s Susanna now seems to be coming down with early-onset Blanche DuBois disease, telling John that there never was a baby, and that she lied to get him to love her. Growing increasingly paranoid and unstable, Susanna becomes fixated on the notion – left less-than-spelled-out by the film but clear to anyone with a working brain – that her father’s slave was her actual mother, and her obsession, along with the general culture clash, prompts John to move her back up north with him, just in time to be on the safe side of the Mason-Dixon line when the Civil War breaks out.

For its first half or so, Raintree County hums along like this, with incident and characterization but little in terms of clear forward thrust. The burnt-out antebellum mansion and the mysterious dead mother are sufficiently intriguing, but don’t contain nearly as much allure as, say, the strange mansion and mysterious dead wife of Rebecca. And when the war comes, the story gains more external threats but loses something of that untouchable North-South tension.

Eventually, the war ends, Abe Lincoln is killed, Susanna gets even more unstable, and John and Susanna have a son, little Johnny. In the film’s final sequence, a now completely out-of-it Susanna runs off to find the raintree in the middle of a swamp, and the four-year-old Johnny runs off after her. John and former love interest Nell go off to find them, reigniting their passion, while Susanna dies in the swamp. In the last scene, John and Nell rescue little Johnny and bring him home, just after the child finally discovered the shimmering gold raintree that legend foretold.

In many ways, Raintree County – directed by Edward Dmytryk, written by Millard Kaufman, and distributed by MGM – is an attempt to present “Gone with the North,” a Gone with the Wind for 1957, post-WW2, post-Brown v. Board, post-Emmet Till, when explicit racism was harder to justify than in 1939, at least outside of the South. With a Nat King Cole theme song, implications that one of the main characters is biracial, an abolitionist lead character, and a clear preference for the romanticism of the North over the romanticism of the South, the movie is a kind of white northern liberal’s take on the 1939 epic with an eye pointed towards a certain ideal of equality rather than the “cavaliers and cotton fields” fantasia of Scarlett O’Hara’s world. The film’s poster proclaims that Raintree County – adapted from a novel of the same name by Ross Lockridge, Jr. – is “In the Grand Tradition of Civil War Romance” and film’s overall two-part epic struggle and Civil War love story calls to mind Gone with the Wind about as much as MGM presumably intended. Even the central love triangle – torn between the sweet but boring blonde and the dangerous dark-haired one – is a gender swapped take on GwtW Scarlett-Ashley-Rhett story.

But for a film of great superficial ambition – three-hour runtime, big budget sets, iconic movie stars, battle scenes shot in glorious Technicolor, and a decade-spanning timeline – to settle for mere pale imitation of Gone with the Wind leaves the film feeling like less than the sum of its parts. Clift’s John Shawnessey is a cipher whose equal passions for equality and Susanna only register in the abstract; Saint’s saintly good girl is even duller, and weird subplots about a footrace between Clift and a mustachioed Lee Marvin, or a pontificating schoolteacher running off with a student, feel like vestigial organs that never quite detached from the source novel.

For all these reasons – aesthetic and cultural, moral and materialistic – it’s not too surprising that the story of Raintree County failed to usurp the position that Gone with the Wind held in the public imagination. The truth is that where Raintree County finds its greatest meaning is in a place remarkably undefined: the raintree.

In the film, what the raintree actually is or does or is notable for is pretty hazy, yet it represents something of an idealistic hope, and the image of it is undeniably attractive – it is something we want, something we search for, something intuitively know is out there somewhere, yet seems to remain perpetually out of grasp; like the peace that comes after a long and painful war, or the freedom after a long and painful bondage. At the end of Raintree County, the family finds the raintree, but that image, that figure – it is something that America in 1957 had not found, something that they were less interested in than the long-gone imagined aristocracy of Gone with the Wind.

I guess we’re still looking for that raintree.

*which of course falls apart when one thinks about it with non-racist eyes.

**1865 was perhaps the last time that Indiana would be called “egalitarian-minded”.