Tune in Next Week is an ongoing feature, examining serials one chapter at a time. You can watch Chapter Nine here.

So far, I haven’t mentioned the directors of Buck Rogers, Ford Beebe and Saul A. Goodkind. Two credited directors isn’t that unusual (two of the best-known serial directors, William Witney and John English, almost always worked as a team), but in this case it’s reasonable to assume that Beebe was the primary director in terms of staging and directing the actors. Beebe was a veteran writer and director who had begun his career in the silents and spent most of the 1930s and ’40s directing serials, including the Flash Gordon and Green Hornet serials, among others. When the serial era waned in the 1950s, he continued directing jungle, Western, and mystery films. His was a solid if unremarkable career in B pictures, his longevity a testament to the “poverty row” director’s essential skill of doing much with little.

Goodkind, by contrast, was credited as director on only three films, but was an editor on more than fifty. His skills were as essential as Beebe’s, considering the logistical challenge of cutting together twelve chapters incorporating live action, miniatures, stock footage, and the dazzling geometric wipes that we’ve seen throughout Buck Rogers. (Three editors are credited as well.) However much time Goodkind actually spent behind the camera, it’s safe to say that his prior editing experience would be an asset on such a production.

Although we’ve pointed out a few interesting framing devices or shot choices over the past few weeks, the emphasis in the serials was on clear and functional staging, and the task of directing a serial was often as much one of assemblage as artistry. In addition, the tight budgets and considerable length of serials meant that there was rarely time for multiple takes: as William C. Cline (author of Serials-ly Speaking) pointed out, the motto of the serials was “Do it as well as you can, but do it only once!”

Finally, it’s worth noting that in the time period under discussion, it was not the director but the producer who had the final say in shaping the finished product. In the serials, producer Sam Katzman was more renowned for his ability to make a profit (it was said that he had never lost money on a production) than for the sometimes variable quality of his films. Producer Nat Levine insisted on standards that became the basis of a house style as the Mascot studio transformed into Republic, strongly influencing the serial genre as a whole in the process. Buck Rogers associate producer Barney A. Sarecky produced serials throughout the 1930s and ’40s and continued in the television era into the 1960s (it’s often said that television ended the reign of the weekly serial at the cinema, but of course it’s more accurate to say that the serials moved to the new medium, bringing both talent and production facilities with them).

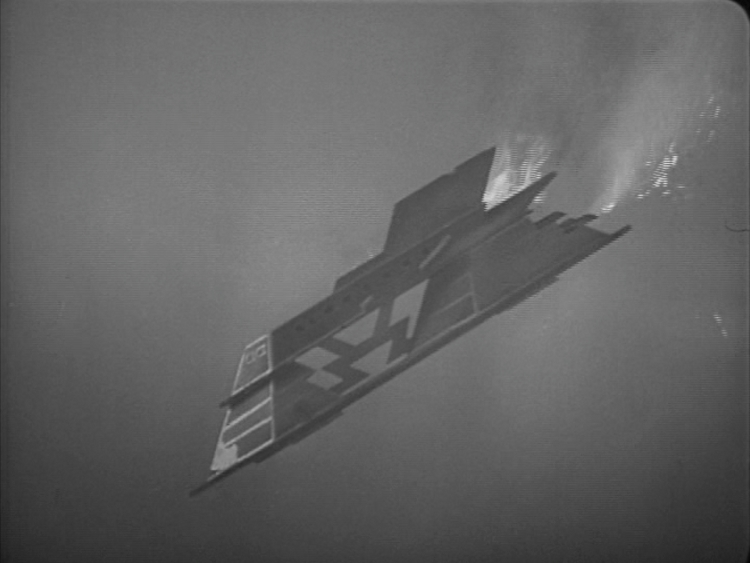

Back to our story: now, this is a clearer example of a cheat, or at least a misdirection. At the end of Chapter Eight, Buck Rogers and Wilma Deering experienced a mid-air collision with one of Killer Kane’s patrol ships while returning to Earth. Reviewing the footage, a fiery explosion was clearly visible, but the scene cuts away just after the impact. However, at the beginning of Chapter Nine, the collision turns out to be a glancing blow, and the ship, disabled, descends for a desperate crash landing. However, Buck and Wilma aren’t out of danger yet: as Dr. Huer and his Hidden City allies watch in horror, Kane’s patrol ships descend on the wreckage. There’s no way the Hidden City forces can rescue Buck and Wilma before they are captured, assuming they even survived the crash.

As it happens, Buck and Wilma were knocked unconscious in the crash; we see Kane’s men carrying their limp bodies from the remains of the ship. Later, Captain Rankin reports seeing the devastation firsthand and is skeptical of anyone being able to survive. A good portion of the episode is made up of Huer, Rankin, and Kragg trying to convince Buddy (recuperated after his injury way back in Chapter Five) that Buck and Wilma must surely be dead.

Buddy is having none of it, marshaling theories and possibilities–perhaps they bailed out with antigravity belts, or maybe they were captured by Kane’s men–and even showing a flashback to an earlier incident through a previously unseen device (the “pastoscope”) that allows Dr. Huer to view past events, even those that occur on other planets.

Many serials would have a chapter incorporating flashbacks or recapping previous events. These chapters served the purpose of catching up viewers who might have come into the serial late or refreshing the memory of incidents from weeks or even months before, but their primary justification, just as in “clip shows” on television in later years, was to save money and stretch out the production’s sometimes meager resources (hence the nickname “economy chapter”).

Although this isn’t quite as bad as some economy chapters–there is only one flashback, and there are other plot developments in this chapter–the scene has the typical setup of one: characters stand around, recounting previous experiences as a pretext to recycling footage. (In this case, the scene is literally framed by Dr. Huer’s viewing screen, a device frequently seen in this serial.) I’m not even sure of the relevance of the scene Buddy chooses: it proves that Kane’s men would rather take prisoners than kill on sight, I guess. I suspect the real reason for this flashback is that the chapter is otherwise a little short on action.

Unconvinced by the cold logic of Huer and Kragg’s realism, Buddy persuades Captain Rankin to airdrop him into Kane’s city for a one-man rescue mission. As usual, Buddy would rather ask for forgiveness than permission, but his appeal to Rankin’s loyalty (“Buck Rogers wouldn’t run out on us if we were in trouble, would he?”) convinces the soldier that the risk of court-martial is worth the chance. Buddy infiltrates Kane’s conference room under cover of darkness and surfs through the surveillance channels until he sees Buck.

And what has happened to our hero? Previously, Kane had expressed grudging admiration for Buck Rogers, admitting that his own soldiers were outmatched by the twentieth-century man. Kane offers Buck the opportunity to betray the Hidden City in exchange for a place in Kane’s empire, but he has misjudged his target’s character, and of course Buck refuses. Wilma is nowhere to be seen, her fate unknown. If Kane understood Buck better, he might try to use Wilma as leverage, but that option doesn’t come up, and we’ll have to wait to find out her fate.

Since Rogers isn’t willing to play ball, to the robot battalion he goes. With one of the amnesia helmets strapped on (and after being forced to polish Kane’s boot!), he is put to work in the dynamo room. (As one of Kane’s councilors points out, with the helmet on all of Rogers’ intelligence about the Hidden City goes to waste.) That’s where Buddy finds him on the viewer.

And it’s at the viewer that Buddy is standing when Kane enters his conference room and takes Buddy by surprise. After exchanging raygun blasts with Buddy, Kane summons his guards; Buddy is shot and crumples to the floor before he can escape. Will Buddy survive, and if so will he end up a mindless laborer alongside Buck Rogers in Kane’s robot battalions? Tune in Next Week for Chapter Ten, “Breaking Barriers,” in what I hope will be a heartfelt exchange of dialogue that breaks down the barriers of misunderstanding that are the real walls of Killer Kane’s prison. (“Killer” Kane–see how much damage labels can do!)